YOUNG TALENTS

Designing for everyday life

Anna Moldenhauer: Before studying industrial and product design you trained as a watchmaker, a profession which demands extremely precise work with filigree structures. How has this combination of skills and knowledge influenced your current way of working?

Eric Geißler: As a watchmaker I am basically a locksmith for all things very small. I am well-versed in metalworking and sometimes there is a creative, inventive element to this kind of practical training, too. I was fortunate in that there are well-equipped workshops at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar and Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle where I had the opportunity to experiment directly with various materials. Accordingly, at the time I rarely held a pencil in my hand. Occasionally, my employers have intimated that I am a bit of a perfectionist as precision sometimes takes up too much time – this perhaps has something to do with the fact that it is essential in the watchmaking trade.

In your opinion, was enough time allocated to explaining what to do after completing your training?

Eric Geißler: My studies have usually been more concerned with the ideal concept than with generating aesthetic variants of the kind presumably taught in classic industrial design disciplines. By working in the workshops, we did, however, acquire a good feel for materials and production techniques, something that is also called for in the design studios. With the benefit of hindsight, I am extremely satisfied with the teaching content at the universities where I studied. For me, however, being a freelancer represents an extreme challenge. As I am more of a product developer and less of an entrepreneur. At this point, I must admit that. (laughs)

What was the starting point for your research into compostable biomaterials for small electric appliances?

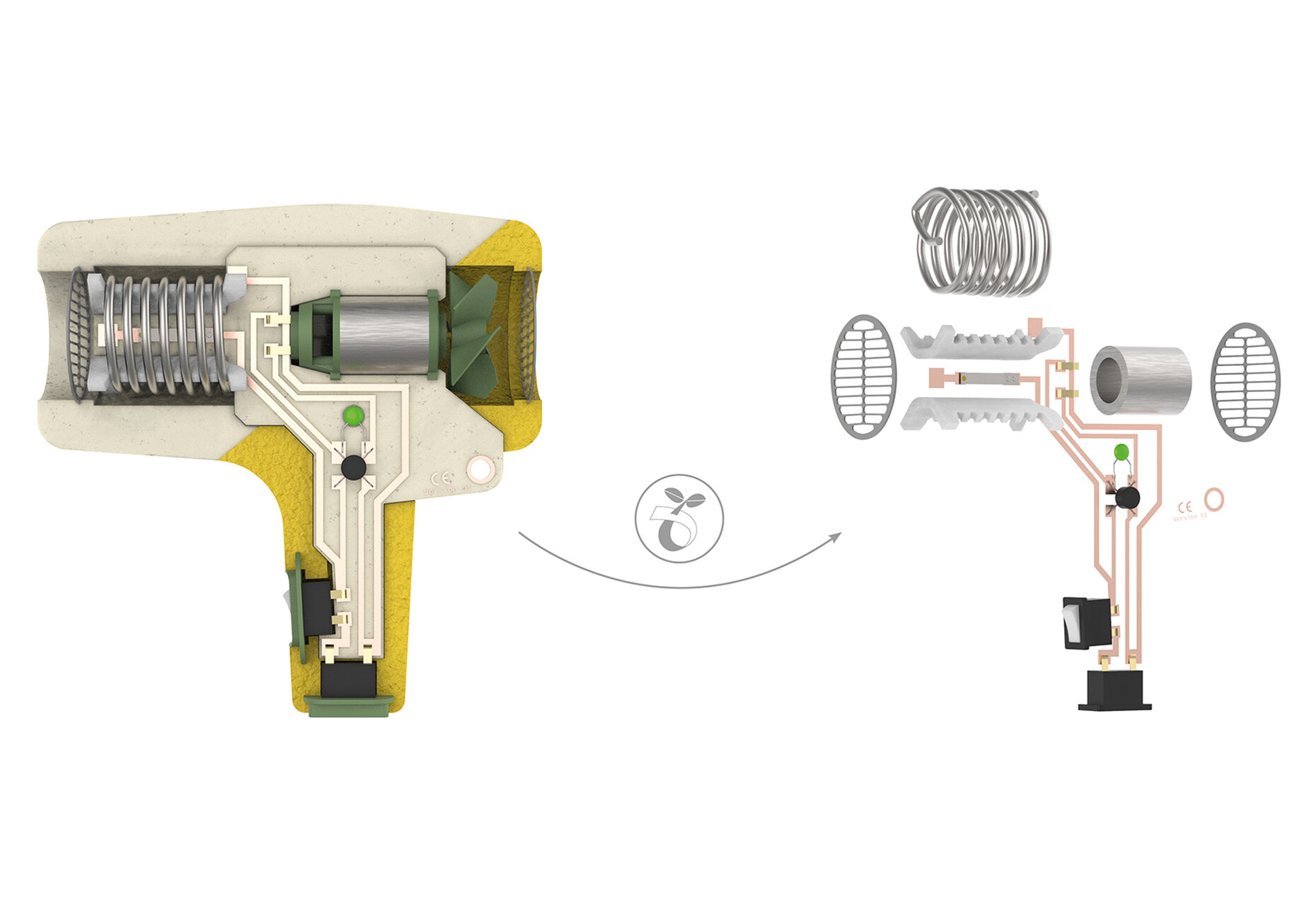

Eric Geißler: In my two years studying at Burg Giebichenstein, I realized a particularly large number of projects for Prof. Mareike Gast focusing on materials, technologies and sustainability. During that time, I had the opportunity to work in the Burg’s own BioLab and to design sustainable futures using microorganisms. Electronic scrap is one of the fastest growing waste streams and it was my objective to take an approach to this problem that was as innovative as possible. There are already a large number of good strategies for recycling electronic scrap such as “design for repair” or “design for disassembly” but in my research I discovered that nobody takes up a screwdriver to recycle anything anymore, independently of how suitable the relevant item is for taking apart. Moreover, many functioning appliances sadly end up on the electronic scrapheap. Presumably, they have simply become too dirty or too unfashionable for their owners. Accordingly, I looked for a new concept that focuses on the end of a product’s lifespan. My concern here is not only, as people often assume, replacing plastics, but especially on the best way to recycle their comparatively very valuable metals. An appreciable volume of these is lost in the current recycling system, due to the phenomenon of “metal substitution”.

Why did you opt for biomaterials?

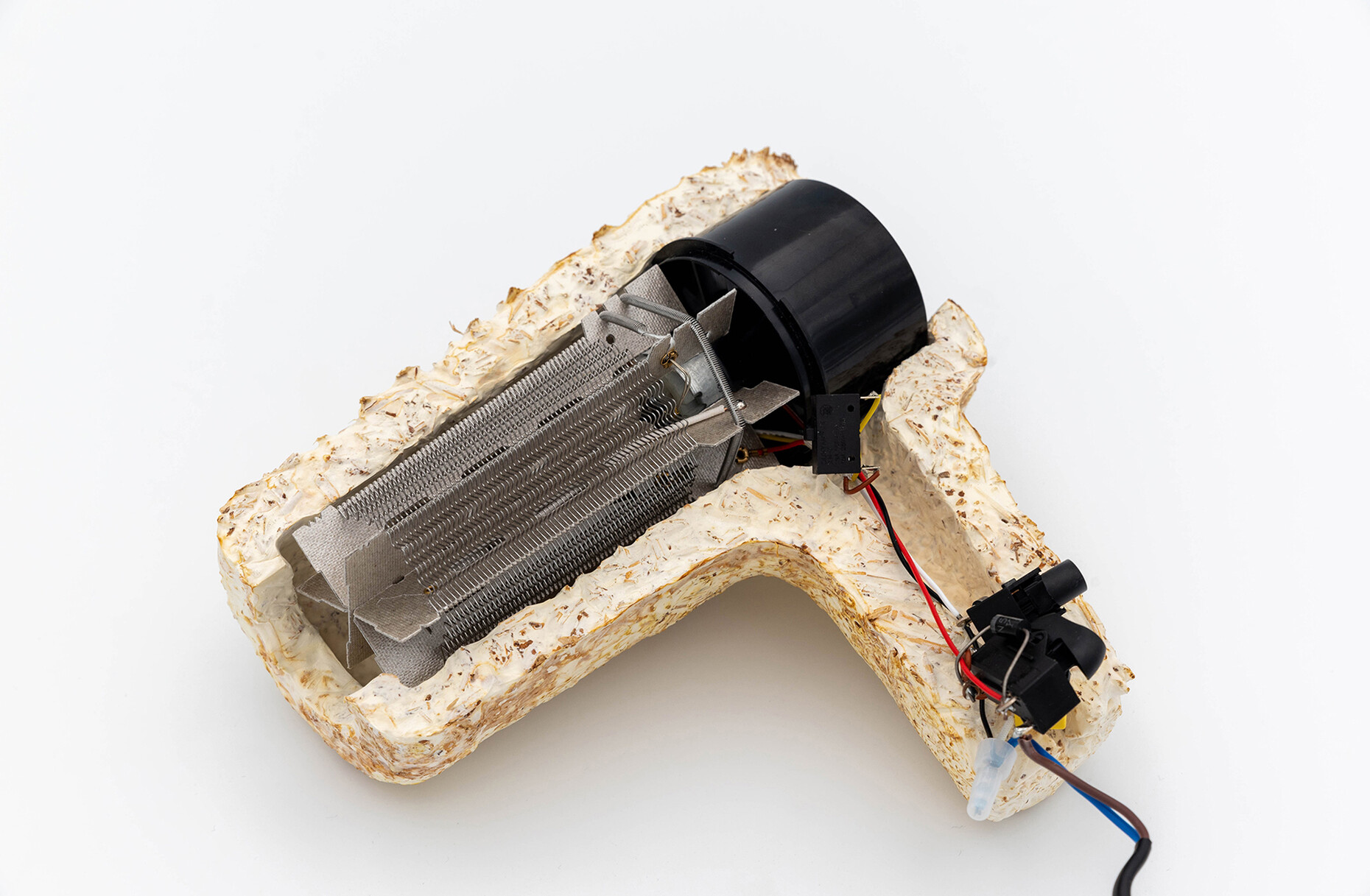

Eric Geißler: My idea was to design an appliance that “takes itself apart” by means of a decay process, one that ends up with its component parts being separated and correctly sorted. To begin with I thought about paper pulp which dissolves in a water bath, releasing all the parts inside it. However, paper pulp is a downcycled version of paper, meaning that for it a tree would have to be felled and processed. What is appealing about the new biomaterials is their extremely small ecological footprint if they can be made from residual or waste materials. Furthermore, fungus mycelium is a natural flame retardant, an insulator and heat resistant up to 250°C, i.e. ideal for use in electrical appliances.

And a great deal of water is called for in papermaking.

Eric Geißler: Exactly. Meaning that the entire process consumes resources. Even if a great deal of power is used for it at another point, it is true that increasing digitization means that at least the manufacture of print (paper) products is declining and thus that there is, if nothing else, less of one raw material for pulp. I imagine that there will still be waste products from agriculture and forestry 100 years from now. This is why I started researching into processing biomaterials manufactured on the basis of microorganisms.

Have you been able yet to test how long the degradation process would take in a casing made of fungus mycelium?

Eric Geißler: It should be possible to make a hairdryer biodegradable if necessary but utilizable for as long as possible up until that point. Indeed, there are fungus mycelium composite products already in use in the packaging industry as compostable polystyrene substitutes. I was able to considerably strengthen the basic material by using a pressing process. I could then use it for the hairdryer’s circuit board and its casing elements. I have been testing a material sample in my apartment’s eaves guttering for nine months now. So far, it has lasted pretty well despite the weather conditions. It is only in the sections that are permanently submerged that the degradation process has started. Ergo, a situation with splash water cannot harm the fungus mycelium. The next step would be to test it in a compost situation where the degradation process would be bound to start earlier.

During the planning phase did you come across all the guidelines relevant to the market launch of small electrical appliances?

Eric Geissler: A market launch would not be possible at the concept’s current stage. In the first instance, therefore, “CompoDry” should be considered a source of inspiration intended to direct people’s attention to the resources problem caused by electrical waste.

How do you produce the fungus mycelium?

Eric Geißler: There are types of fungus that are very suitable for making the material, such as Ganoderma lucidum, also known as reishi. It grows rapidly, something that makes contamination more difficult and is even quicker than mold. It can be “fed” with wood or scraps of food. At Burg Giebichenstein I had the opportunity of producing these fungal materials in the biology lab in a sterile environment and with the relevant tools.

The projects you realized during your studies are solution-oriented, be they ways to make everyday life easier or introduce changes to the systems people use. What is it about this kind of work that interests you more than designing furniture, for example?

Eric Geißler: This has a lot to do with the challenges in the relevant projects. As a budding student I read, first and foremost, the books by Charlotte und Peter Fiell on the history of design, a process which largely takes its inspiration from making furniture such as chairs – that was also something I was drawn to. Accordingly, I was initially surprised but later very happy when they told us that for our bachelor’s degree at Bauhaus-Universität Weimar “we do not make chairs anymore, there are enough of those around already. Amongst other things, we look at the problems experienced by fringe groups who don’t have lobbies of their own.” I was very glad that my studies were looking into the kind of topics that do not necessarily immediately culminate in commercial exploitation. Such problems are not always easy to solve but I have nevertheless attempted to come up with a practice-oriented design in each case so as to be able to offer people a plausible product.

What are you currently working on?

Eric Geißler: I presently work for a Munich-based design agency as an industrial designer, primarily developing products for small to medium-sized companies.

What developments would you like to initiate in the sector in the immediate future?

Eric Geißler: Possibly as a result of that idealism that I developed during my time at university, I don’t think that “design-to-cost” and sustainability are necessarily mutually exclusive. The “undiscovered gems” among the design classics are those items for which only as much material was used as was required for its designated purpose. Of course, the products must also be designed to sell and thus to a certain extent appear stylish for the current zeitgeist. I would nonetheless hope for slightly less “opulent” solutions.