A Ray of Hope

Tripoli, the second largest city in Lebanon, and located in the northern part of the country, has often been underestimated. This is not only because most investments take place in Beirut, or that Tripoli has the reputation as being both “poor and dangerous”. Since 2019, the entire country has been in a severe crisis – politically, economically and socially. There has been no elected government since last October, the Lebanese pound is in free fall, and the population is becoming noticeably impoverished. Moreover, in August 2020, a huge explosion of improperly stored ammonium nitrate in the port of Beirut destroyed large parts of the city – the country's economic centre – in the midst of a global pandemic. This is anything but a good situation in which art, design and architecture can flourish. Amidst all the misery, however, small rays of hope are beginning to emerge in Tripoli. The city has just been named the “Arab Capital of Culture 2024” by the Arab League, which is finally bringing it more favourable publicity, both inside and outside the country. Tripoli had numerous cinemas and theatres before the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), but there's a great deal more to discover. Between the historic old part of the city and the port lies an architectural gem that deserves to be discovered: the Rachid Karami International Fair, designed by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer between 1962 and 1975. The permanent fairground was originally expected to receive up to two million visitors a year, but the outbreak of the civil war prevented the completion of the buildings and the fair never opened.

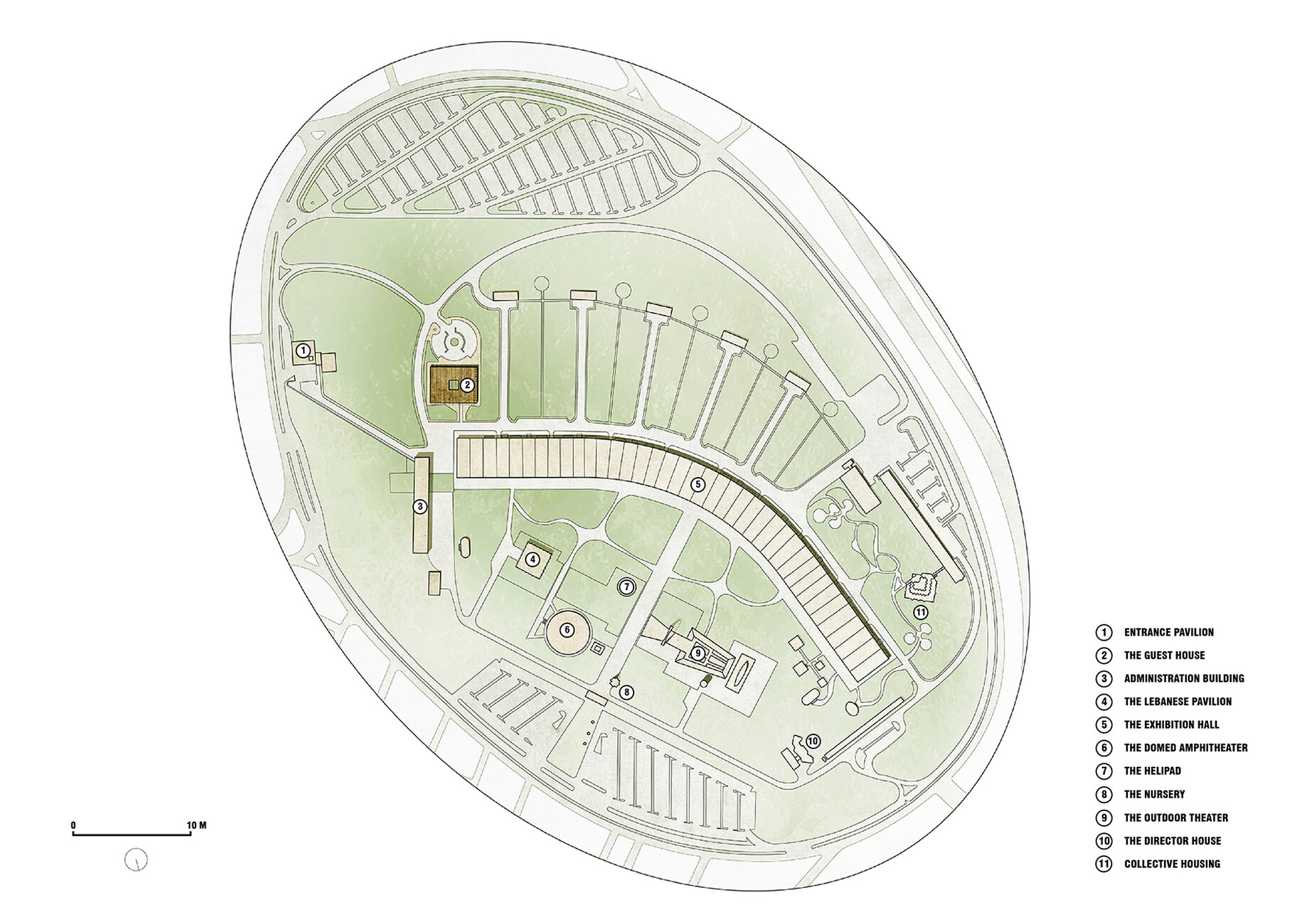

In January of this year, the ensemble, which is set in a well-tended landscape park, was added to UNESCO's List of World Heritage in Danger. Oscar Niemeyer's design is “an outstanding example of 20th-century urban planning and architecture,” according to the text in the application for inclusion on the World Heritage List. Main buildings such as the large exhibition hall, the Lebanese pavilion, the amphitheatre and the director's villa, as well as numerous adjacent buildings, are located on the 72-hectare property. Some of the striking structures have been renovated and remodelled beyond recognition – sometimes with complete disregard for Niemeyer's ideas – or even destroyed over the years, or have fallen into disrepair due to corrosion of the steel and ageing of the concrete. Parts of the fair are also overgrown with trees and scrub.

A 72-hectare architectural icon

From Beirut, we head north on the country's only motorway, with the Mediterranean always in sight to the west. We are travelling with Charles Kettaneh and Nicolas Fayad, the two founders of East Architecture Studio. The two men in their mid-30s met while studying architecture at the American University in Beirut. The conversion of Niemeyer's guest house was their first major project, they say, but of course they knew the architectural complex beforehand, having visited the exhibition centre as students. It was not until the awarding of this prestigious commission, however, that they really delved into the project, studying the work of the Brazilian architect and searching the city's archives for plans and other information. They also contacted the Oscar Niemeyer Foundation in Rio de Janeiro, but had little success there. After construction was halted, Niemeyer distanced himself from the project and almost never mentioned it again, say Charles Kettaneh and Nicolas Fayad – which may have contributed to its being forgotten. That this situation is finally changing is also due to the fact that East Architecture Studio received the prestigious Aga Khan Architecture Award for the conversion last year. Charles Kettaneh is pleased to report that this has also led to an increase in requests for their involvement in the conversion of other listed buildings.

Coming from the motorway, you almost need to drive round the entire fairgrounds, which have been fenced in for some time now. But that's how you really become aware of the size of the site. The forecourt alone is huge – with a kiosk that was intended to be used for ticket sales, an administration building, and a wide overhanging roof structure that marks the entrance to the fair. We drive over a ramp that Niemeyer originally intended to surround with water, which would have had a very compelling effect. Slightly elevated, it's possible to overlook the entire fairgrounds from here. Some of the buildings, such as the water tower and the amphitheatre, are very striking because of their clear geometric shapes.

We turn off in front of the 700-metre-long exhibition hall known as the Boomerang and reach the guest house. The building, converted by East Architecture Studio, sits on a large lawn and is barely protected from the scorching sun. It appears to be hermetically sealed, as the facade is windowless. Gravel is used as a paving material in the outdoor areas – according to the young architects this was inspired by the colours, textures and materials used by landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx for the projects he worked on with Niemeyer. Minjara is written in large letters at the entrance; the sign indicating the project's new use. In the mid-19th century, Tripoli developed a thriving wood and furniture industry, although not much of it remains today. Supported by the European Union, Minjara, a platform founded in 2018, aims to help local artisans and furniture makers by providing both business contacts and well-equipped workshops. Minjara also exhibits its own furniture collections in this converted building.

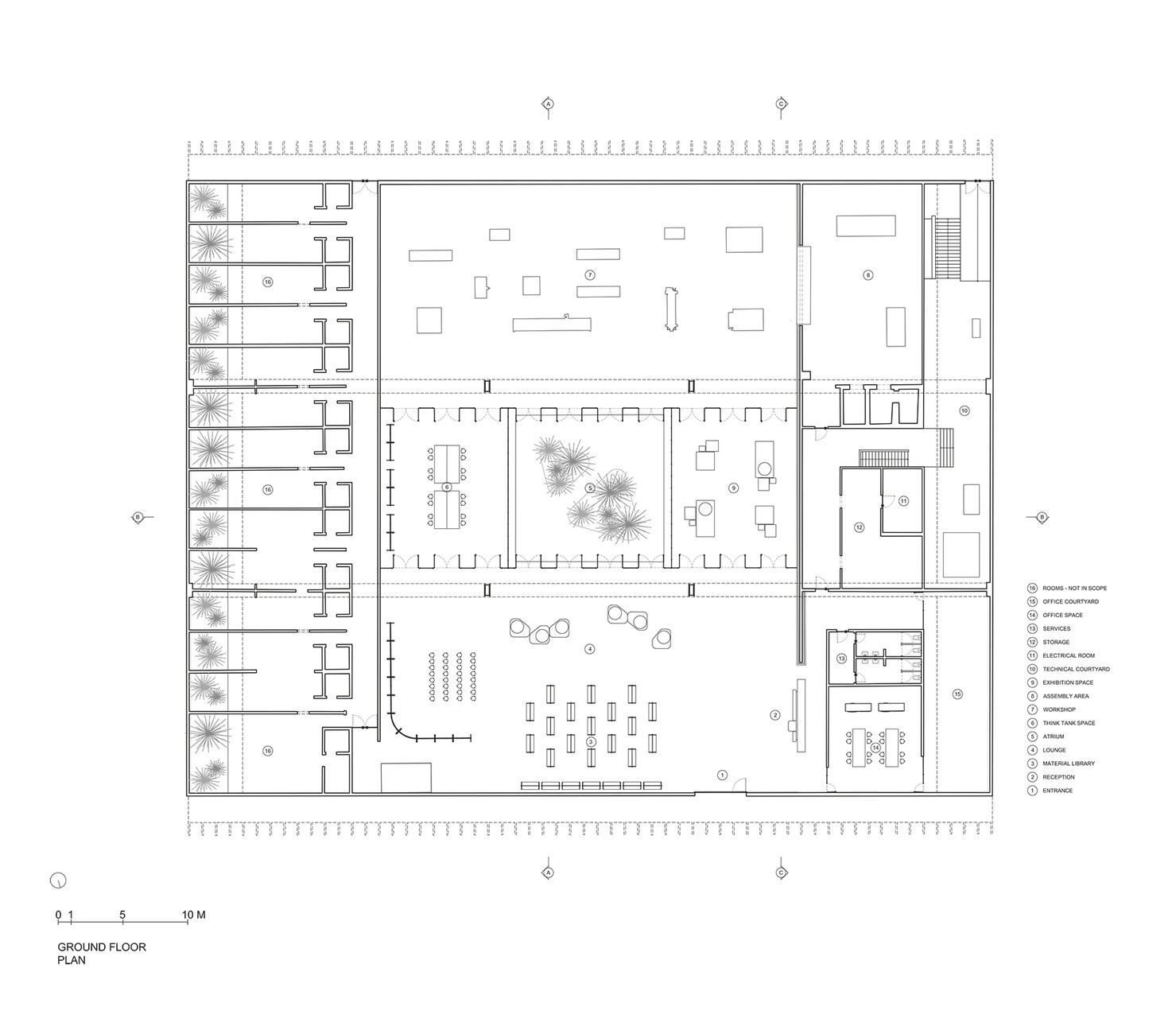

The approximately 2,500m2 former guest house has been divided into two main parts: The spaces formerly open to the public now house Minjara's carpentry workshops, showrooms and offices – this area was remodelled and renovated by East Architecture Studio within a tight deadline of just four months. In the rear section of the building, Niemeyer's plans called for 14 guest rooms with private bathrooms and courtyards, which are now in a semi-finished, unrenovated state due to cost constraints. The interior of the building has a central atrium with floor-to-ceiling windows on four sides, allowing natural light to stream into the surrounding rooms. The open space of the courtyard is planted with grasses and covered with a striking grid pattern made of reinforced concrete struts, which create an interesting interplay of light and shadow. The view from the courtyard extends into the large adjacent workshops, exhibition rooms and materials library, while the offices, wash rooms, storage and technical rooms are all located behind the workshops on one end of the building.

Careful renovation

East Architecture Studio based their project on other buildings completed by the Brazilian architect, with all of their interventions being reversible if ever desired. These include, for example, the added glass doors with fine metal frames that effectively separate the large-scale spaces. They take up the grid of the concrete ceiling, without actually touching it. They also cleverly separate the large spaces from each other. The new concrete flooring was laid in such a way that it does not quite reach the original natural stone walls, which provide a nice contrast to the guest house's sober, straight-lined architecture. For this design element Niemeyer drew inspiration from traditional Lebanese architecture. The structural elements have been cleverly hidden behind plywood panels by East Architecture Studio, while the ceiling light fixtures are custom-made to match the ceiling grid.

The master plan developed by UNESCO and the Getty Foundation aimed at the revitalisation and holistic preservation of Oscar Niemeyer's Rachid Karami International Fair site seems hardly feasible given the political and economic circumstances in Lebanon at present. But at least a promising start has been made with East Architecture Studio's conversion and the reuse of the guest house – especially considering that the budget was only about $750,000. Charles Kettaneh and Nicolas Fayad are now hoping they can turn the building's 14 unused guest rooms into a proper guest house. There must be plenty of people interested both in architecture and Oscar Niemeyer who would like to spend a night in these historic surroundings.