From Devon to the world

“For the rigor, integrity and relevance of a body of work that speaks beyond architecture for its social and environmental commitment, David Chipperfield is named the 2023 Pritzker Prize winner.”

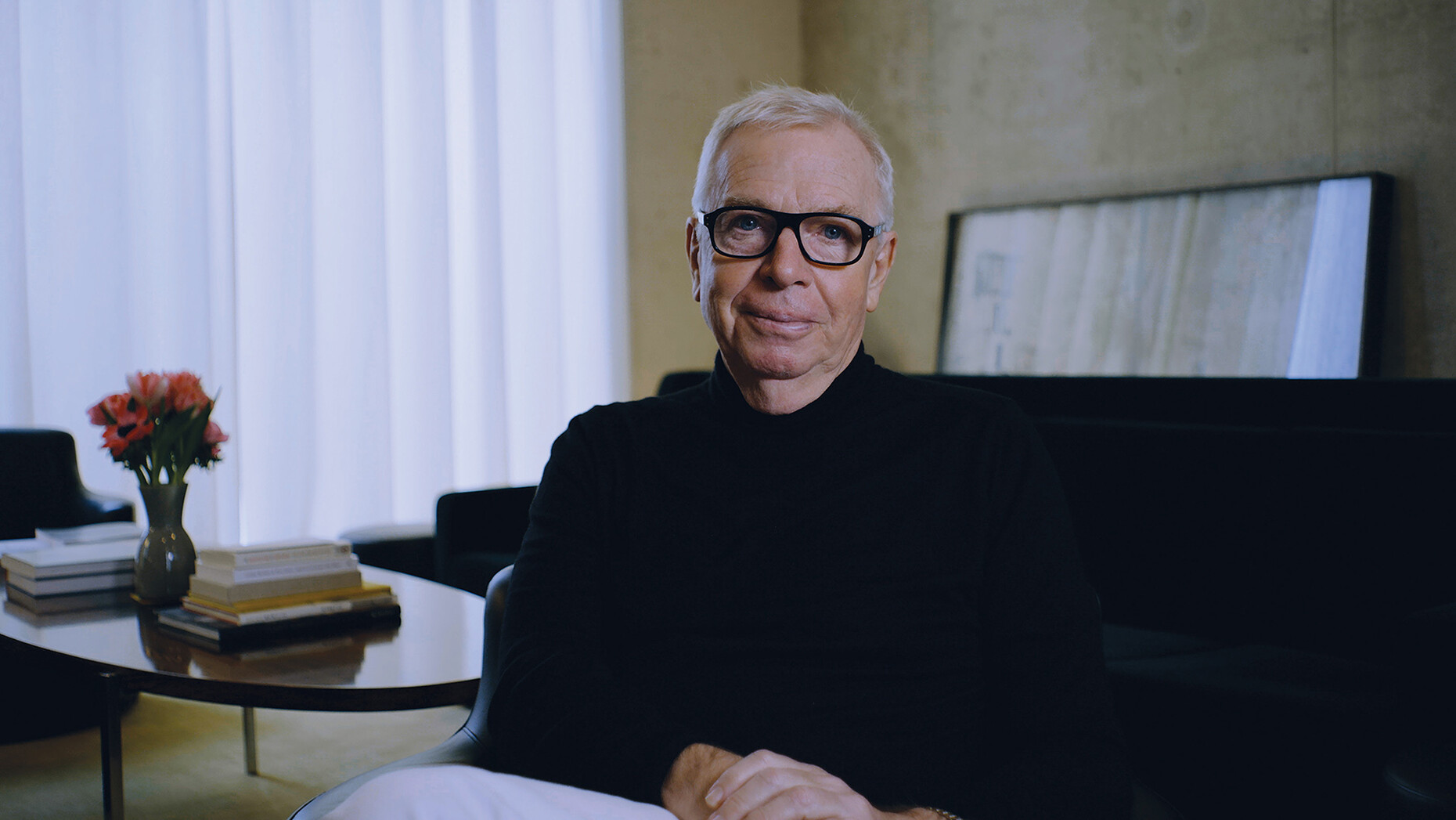

This was the announcement made by jury chairman Alejandro Aravena on 7 March 2023 in Chicago. The Pritzker Prize is the most important architecture award in the Western World. David Alan Chipperfield, born in London in 1953, grew up on a farm in the English county of Devon. He made his first contacts with architecture when his father converted some parts of their own farm, as well as a neighboring farm he had bought, into vacation homes. “Academically fairly hopeless,” as he himself would say, but very good at sports and art, he attended the Kingston School of Art in London and subsequently the Architectural Association (AA), which was also based in the British capital, enjoying a legendary reputation. After experimenting at the Kingston School, the freedoms of the AA lead him to an almost conservative view of architectural modernism and a formal restraint that can be found in almost all of David Chipperfield Architects' later work. Unwelcome at the AA at the time, this attitude was welcomed, of all people, by by Zaha Hadid, whose good words help prevent Chipperfield from failing an important exam and graduating in 1977. He went on to work with Douglas Stephen, Richard Rogers and Norman Foster, among others; the latter two themselves winners of the Pritzker Prize.

England, Japan and Germany

In 1985 David Chipperfield founded his own office and designed, among other things, the interior for the store of Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake on London's Sloane Street. Contact with Miyake opened the door to Japan, where Chipperfield undertook further interior designs for the retail trade, but above all was able to build the Gotoh Museum (1988-1991) in Chiba, north of Tokyo, and an office building for Toyota (1989-1990) in Kyoto. Both are clearly influenced by the exposed concrete chic of Japanese architecture at the time, but already exhibited a preference for clear volumes, soaring, slender wall panels and roof panels supported by filigree pillars or columns that still prevails today. “With shop interiors, the projects in Japan and some competition entries, you could magic up the idea – with sleight of hand – that I had a real office,” Chipperfield admitted recently in an interview with the Guardian newspaper.

But in this way, at the beginning of his career, he also succeeded in making the leap to Germany. Here, over the years, some of his most impressive projects have been created, which the architect now tackles with a steadily growing team. These teams and the office partners were to become important not only for the success of the projects, but also for the view of the native Englishman. Also in the Guardian, David Chipperfield said, “In my generation it was always about the product, but now I believe more than anything that we need to focus on the process." Beginning in 1993, the firm refurbished the August Stüler-designed Neues Museum on Berlin's Museum Island – a project that would span 16 years. In the restoration of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe's New National Gallery (2012-2021) in Berlin, the process also seems more important than the firm's own architectural signature.

Stores, museums and residential buildings

But what this signature looks like can now be seen on and around Berlin's Museum Island. With the Galerie am Kupfergraben (2003-2007), Chipperfield's team showed in exemplary fashion how contemporary architecture can absorb the influences of the site and its buildings and merge them into an appropriate architectural amalgam. The eaves, heights and cornices of the historic neighboring buildings are continued as white concrete block bands and culminate in a cubist corner building whose light masonry is finely countered by dark wood for windows and doors. With the James Simon Gallery (1999-2018), located directly opposite this building, the office completed a kind of Arcadia of its own with a setting that is as self-evident as it is self-confident in urban planning terms, connecting the exhibition venues of the Museum Island in a striking manner, adding an entrance building, and completing the overall ensemble in the direction of the Lustgarten.

About the museums: Over the years, impressively beautiful and very usable exhibition buildings have been built all over the world. The River and Rowing Museum in Henley-on-Thames (1989-1997), the Museum of Modern Literature of the Literary Archive in Marbach am Neckar (2001-2006), the MUDEC in Milan (2000-2015), the Hepworth Wakefield in West Yorkshire (2003-2011), the Saint Louis Art Museum in Missouri (2005-2013), the magnificent Turner Contemporary on the Kent coast (2006-2011), the Museo Jumex in Mexico City (2009-2013) and the West Bund Museum in Shanghai (2013-2019) – to name but a few.

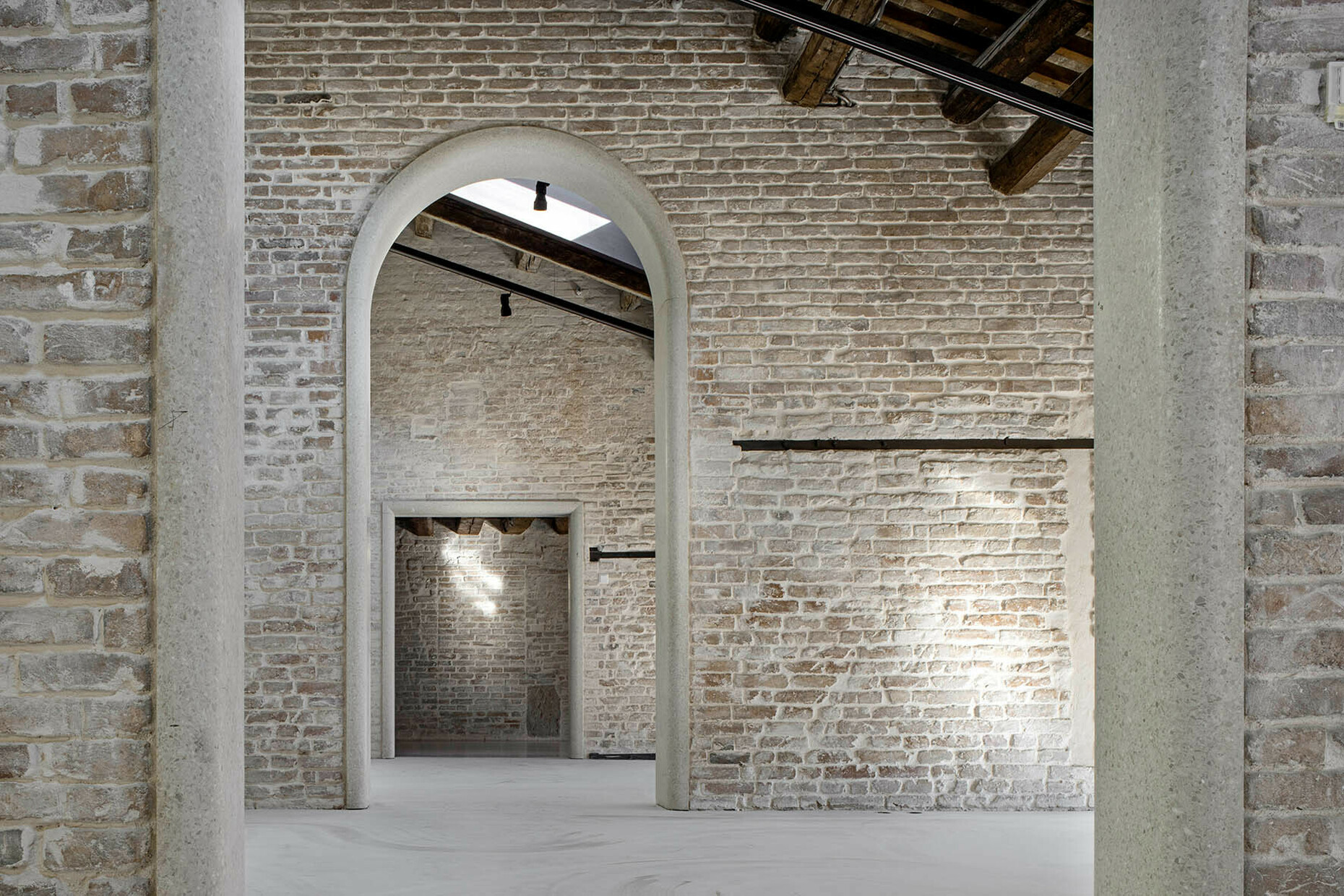

David Chipperfield and his colleagues have continuously demonstrated their special ability to deal sensitively with the built environment, and to work with the architectural heritage instead of against it. The San Michele Cemetery (1998-2017) in Venice already bears witness to this, and most recently this skill became evident, also in the lagoon city, with the redevelopment of the Procuratie Vecchie (2017-2022), which extends over the entire north side of St. Mark's Square. In between these projects, further examples of his ability to restrain himself are emerging, with the Jacoby Studios in Paderborn (2014-2020) and the conversions and extensions as part of the master plan for the Royal Academy of Arts in London (2008-2018).

Honors and a life in Galicia

The debates about the rather uninspired design for the Kunsthaus Zurich (2008-2020) or the Elbtower in Hamburg, which has been in planning since 2017, show that all that glitters is not always gold in terms of his overall work. David Chipperfield also designs private residential buildings far more confidently. In Berlin, a generously proportioned residence (1994-1996) clearly recalls Miesian brick modernism; Fayland House in Buckinghamshire (2009-2013), after a succession of courtyards, opens out into the gently rolling landscape behind a series of massive columns; and in Kensington, these columns are varied in a noticeably slimmer way as the spatial threshold to a luxurious urban villa (2008-2012). The architect inserts his own retreat as a matter of course into the old town development of the Galician fishing village of Corrubedo (1996-2002). Here he retreats again and again, dedicating a considerable amount of work to the village and the region. In the meantime, David Chipperfield runs a bar there, founded the public foundation Fundación RIA in 2017, with which he was commissioned by the Galician government to oversee the regional development plan, and tries to create added value for the village and region by leveraging his own privileges. As a result, in addition to numerous other awards and honors – such as honorary membership in the Association of German Architects (2007), the Royal Institute of British Architects Royal Gold Medal (2011) and the Praemium Imperiale (2013) – he was also awarded the Galician of the Year prize in 2019.

The impressive range of the architectural tasks he has undertaken now makes this latest award for David Chipperfield seem well-deserved as well, as it makes it clear that the appreciation of a single person, in the discipline of architecture, which is increasingly characterized by processes and teams, seems more and more unusual. However, Chipperfield and his entire office are worthy Pritzker Prize winners because of the quality with which their projects are generally designed and accurately developed, down to the smallest detail.