Hybrid

The 15th arrondissement of Paris is located in the southwest of the city, where the Seine and the Ring Boulevards meet. For many years, there was an area south of Rue Lecourbe that, although located in the centre of Paris, was not really part of the city. The RATP (Régie autonome des transports Parisiens), the operator of local public transport in the French capital and its surrounding area, carries out the maintenance of its underground trains here in workshops on more than two hectares. Dominique Lyon Architectes developed a master plan for the site, which extends to Rue Croix Nivert running in a north-south direction, combining industrial use with new residential construction. In this way, the area, which vegetates like a vacuum in the midst of urban life, is to become an actual part of the city. To this end, Dominique Lyon Architectes are laying a new road in an east-west direction through the site and adding flats to the workshops and offices necessary for the RATP. Now, five residential floors rise above the industrial uses on the ground and first floors. These mixed uses are complemented by further residential buildings that continue the existing block structures around the workshops and link the new quarter with the surrounding city.

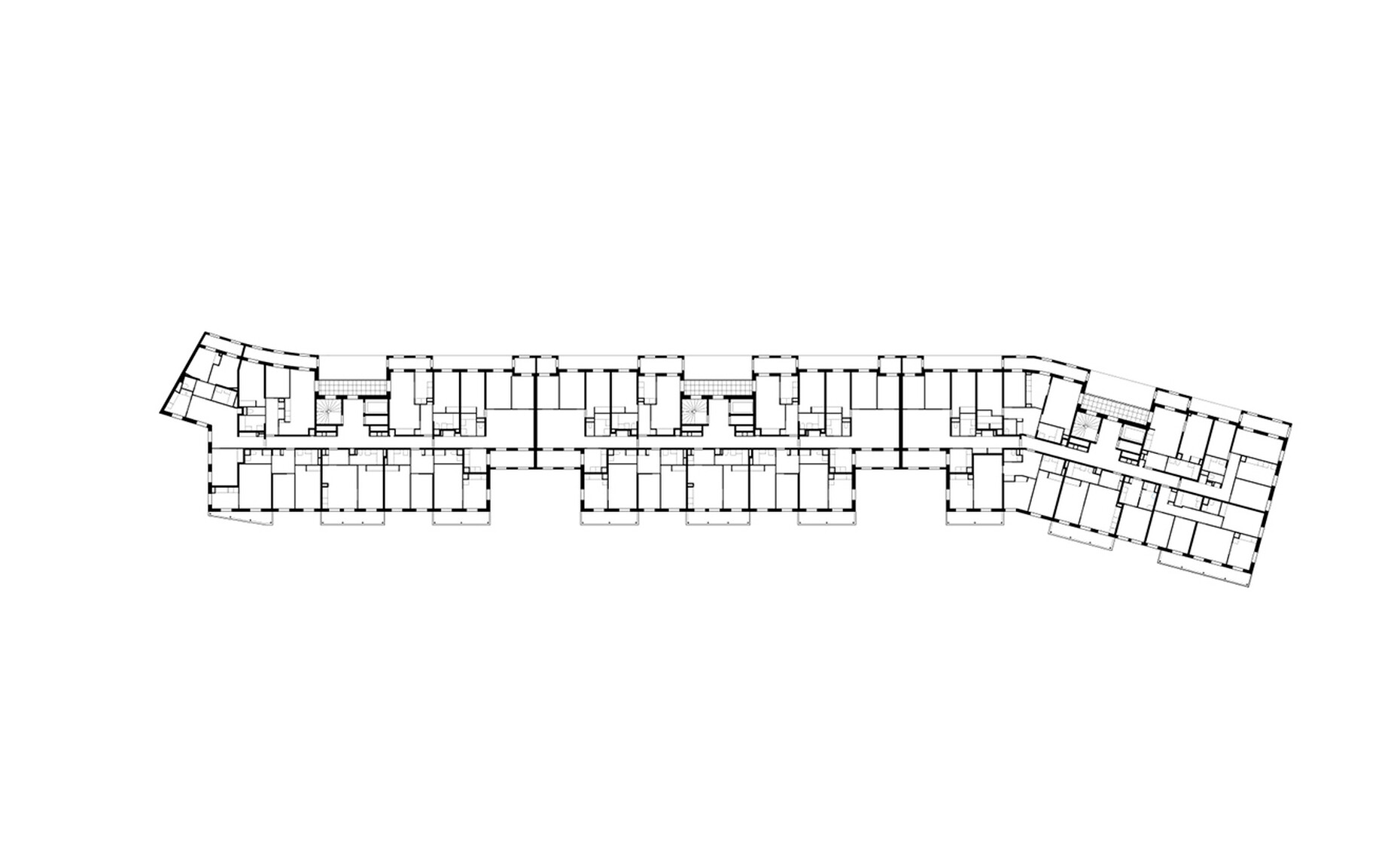

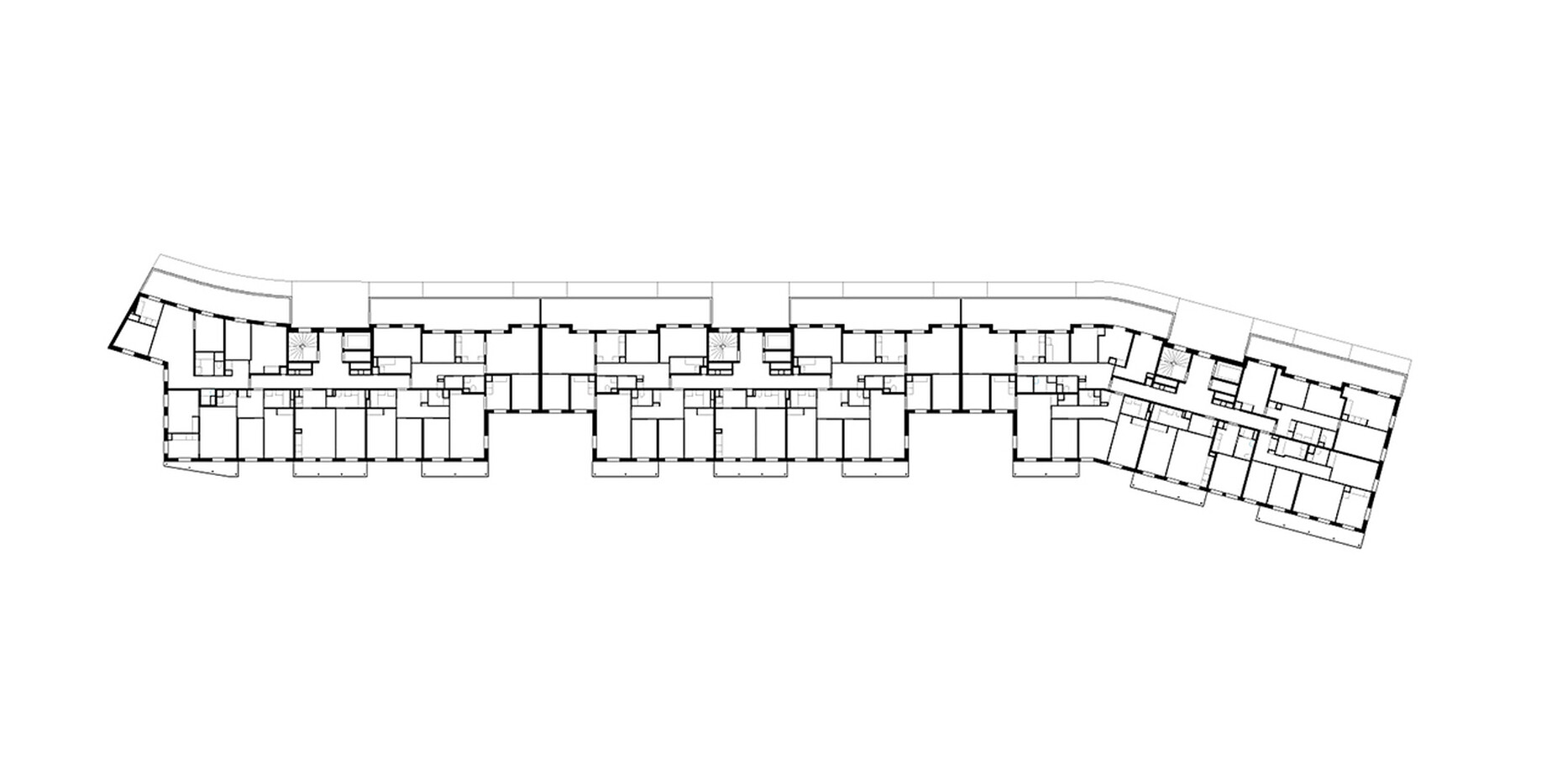

One of the buildings was designed by the Basel architecture firm Christ&Gantenbein and realised on site together with Margot-Duclot Architectes as the local partner firm. The team led by Emanuel Christ and Christoph Gantenbein drew on research that the two had conducted with students at ETH Zurich as part of their professorship. Numerous case studies in Athens, Delhi, São Paulo and Paris were examined to create a kind of catalogue of prototypical typologies for the four cities - the procedure had already been tested in Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, New York and Rome. Based on these considerations, the architects developed a kind of residential snake, 124 metres long, which rises up following the new road on top of the workshop building and to the north of the actual track of the repair works. The spring-mounted construction is independent of the vibrations and shocks of the halls below.

At first glance, motifs of Haussmann's city characterise the long building: A window format developed from the proportions of typical Parisian windows is consistently used for all openings in the façade and also appears again and again in the interior. Balconies and loggias form projections and recesses that appropriately structure the long street frontage and provide variance within the uniform façade shape. The cladding, on the other hand, is consistently and homogeneously drawn over the entire house and, as a clearly painted metallic dress, evokes associations of Parisian roofs and mansards. Beneath the metal cladding of the façade is a reinforced concrete skeleton, which is lined with prefabricated wooden elements. Thus, the house is noticeably a contemporary architecture that is, however, just as comprehensibly rooted in the city's history - especially that of the 19th century.

Both the construction and the cladding kept the building costs within reasonable limits, after all, the aim was to create social housing here. 104 flats now find their place in the city. On the inside, too, a canon of simple, robust, but nevertheless valuable elements was created, which on the one hand remain within the available cost framework of social housing and at the same time provide dignified living spaces. Each flat is allocated at least one balcony or loggia, which in turn do not appear as part of the living space calculation and thus increase the space that is actually available to the residents. In addition, these unheated components serve as a kind of climatic buffer space for pre-regulating the temperatures of the interior rooms.

The architects have developed four types of flats ranging from small studios to large five-room flats, so that a certain mixture of milieus is possible within the building. This house could not only contribute to a functional mix within the neighbourhood, but as a mixed urban building block it could itself contribute to the question of what social housing can look like today.