City of longing

Alexander Russ: You and your in-house think tank caspar.esearch conduct research on the topic of retail, and have also organised a series of talks concerning the subject with the Architekturforum Aedes in Berlin. Why are you interested in this particular topic?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: There are several reasons. Firstly, because it affects our daily work. We're not classic retail architects, but we frequently deal with the subject because we plan a lot in an urban context. I also dealt with topics such as the redesign of department stores very early in my career. Secondly, about six years ago we noticed that with many of our projects, which were actually in prime locations within a particular city, it was becoming increasingly difficult for the developers to find tenants.

How did this manifest itself?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: There used to be one property and ten prospective tenants and suddenly there were ten properties and one prospective tenant. A demand-driven market has become a supply-driven market. This has had a huge impact on our planning, and affected our city centres even more.

Can you give me an example of this?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: Sure. A shopping mall was originally planned for the Sedelhöfe in Ulm by MAB, a Dutch project developer. However, our client, who had been awarded the contract after the city of Ulm had put it out to tender again, no longer wanted to build it like this due to the changed market situation. The whole thing was simply no longer compatible with the way urban society is changing, i.e. the increasing use of online retail. We therefore decided, together with the client, to design classic commercial buildings with additional office and residential uses, sited around a public square – in other words, exactly the type of development that has worked very well in European cities for centuries. If a real urban quarter is created instead of a building complex with 80,000 square metres, this will also be more readily acceptable to a city and its citizens. This has shown us, as architects, how to think about the future of the city. And it made us realise that many of the ways we've dealt with retail were unnatural.

In what way?

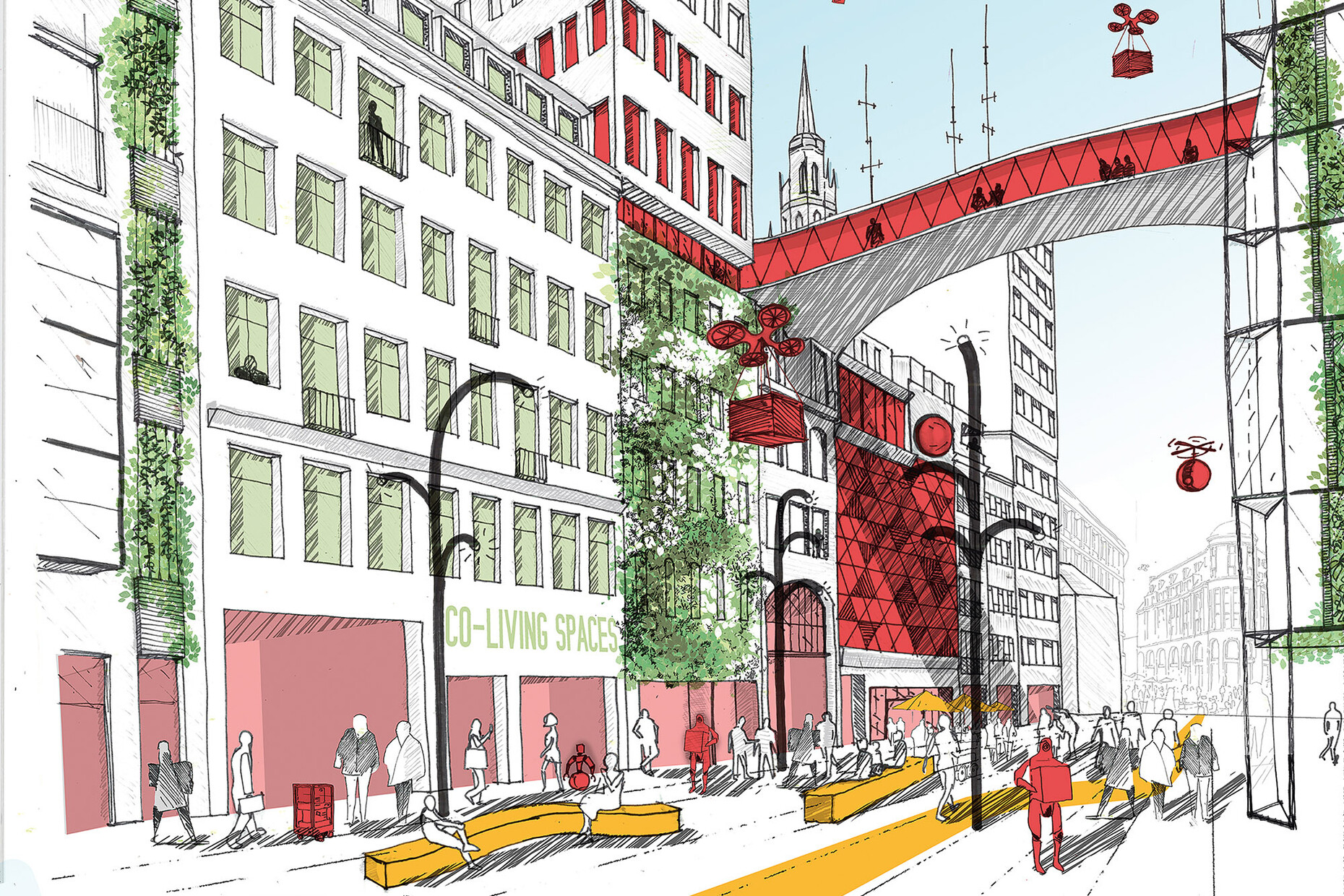

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: For example, the tendency to always want to bring people into buildings, instead of leaving them outside on the streets or in the squares. You know this from big urban centres: After closing time, there's usually nothing going on here, and that's not really the kind of city we want to live in. In this respect then, you could also say that the big changes in the retail sector are also creating opportunities. Digitalisation, which has had a huge impact on retail, will also have a huge impact on the city. Ultimately, this process is not only about the death of retail, but above all about a change in urban space and the way it's used.

I'd like to come back to the topic of mixed use. You just mentioned the example of the Sedelhöfe in Ulm, where this principle was finally applied. Actually, for decades there have been calls to combine living, working and leisure. So why doesn't this happen more often when projects are planned?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: In the meantime there's certainly been a rethink of this – and the strict separation of functions – as was usual in the urban planning of the post-war period, is, in my opinion, a thing of the past. Many cities are now calling for functional mixing. The question for planners is how to reconcile the different functions in a meaningful way.

What are the problems in this regard?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: The danger with mixed use is that people think everything has to happen within one building. You can't always fit everything into one building, however. This is where large projects such as the Sedelhöfe in Ulm have a lot of potential; where we've had the opportunity to harmonise different functions such as retail, gastronomy, office use, hotel and residential. The original planning, by the way, only called for 11 flats on the whole site. Now 110 new flats have been added there, which of course greatly revitalises the neighbourhood. We're very concerned with the question of how best to use the city, and we increasingly find that developers are also interested in this.

You also deal with the topic of retail and the associated transformation processes in your book "Retail in Transition", in which you put forward three theses. The first of these states that new concepts are needed for retail. Can you explain this in more detail?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: With digitalisation and the possibilities of online retailing, there's no longer a real need to go to a store to do your shopping. But if consumers still decide to go shopping, they want to have a special experience while doing so. Some retailers have already understood this and are responding with appropriate concepts.

An example of this would be Querkraft Architekten's new Ikea store in Vienna. They've moved the store from the outskirts to the city centre and offer a completely different shopping concept than the other Ikea stores do.

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: Yes indeed, and that brings us back to the topic of mixed use and the second thesis of my book, which is about encouraging a mixing of functions. The Ikea store in Vienna not only has shopping areas, but also a hotel and even public space on its roof terrace. In addition, the shopping itself is also a hybrid model: The store mainly offers products that are easy to transport, while everything else is then ordered on the internet and delivered. So the future of retail will definitely be hybrid.

The third thesis of your book is about new mobility concepts and the possibilities of a complete mobility transition. Can you elaborate on that?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: Here, too, a great change is now taking place – especially with regard to the use and importance of the car. As planners, we've found there are significant regional differences: In Berlin, cars don't really play a role any more, but when we proposed removing automobiles from one side of the Königsallee in Düsseldorf, it met with fierce resistance. And yet cities like Copenhagen have already shown us how well something like this can work. It would change the use of public space, and, as a result, massively increase the attractiveness of city centres – which brings us back to the topic of the shopping experience. There's still a lot of convincing to be done, however, and this doesn't only apply to urban planning, but to actual buildings as well.

Can you give me an example of this?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: I recently had a discussion with an investor about cycling mobility. We always suggest our clients not hide their bicycle parking areas in basements, but instead put them in an attractive space with proper changing rooms and decent showers, so that it's fun to come to the office by bike. The answer you usually get is that everyone drives a car anyway, but that's because there aren't any proper facilities for cyclists. And it's exactly this provision that can be the deciding factor for tenants to move into such buildings. One example is the new Deloitte headquarters in Düsseldorf, where we have space to park 600 bicycles on the ground floor. In the end, this was one of the reasons Deloitte chose the building.

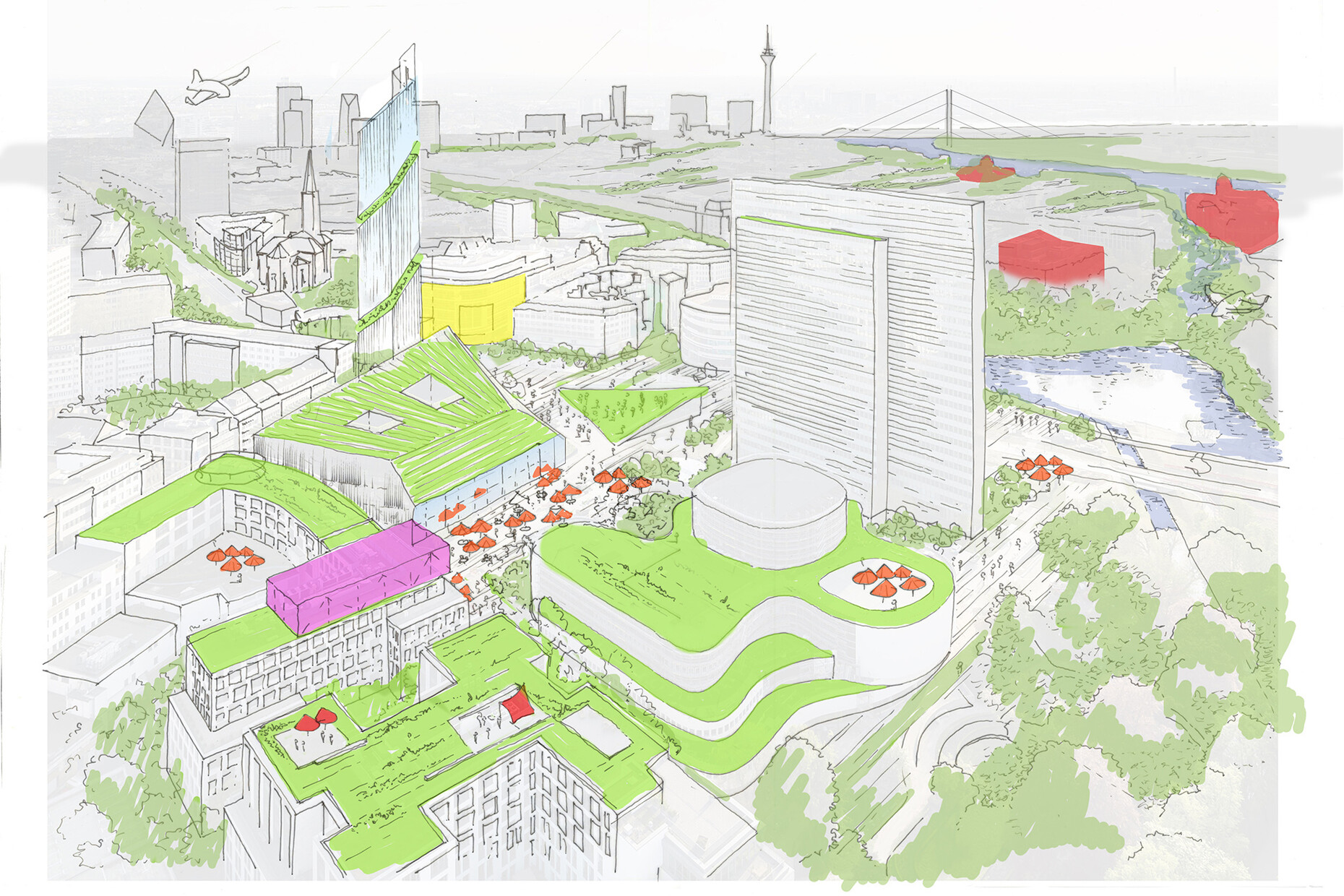

Your book contains utopian architectural sketches for cities such as Berlin, Munich, Hamburg, Düsseldorf and Frankfurt am Main that illustrate your individual theses. In conclusion, what's your perspective concerning the future of inner cities?

Caspar Schmitz-Morkramer: I'm entirely convinced that commerce will continue to be important for cities and will play a central role in them. It just won't have the all-defining character it once had. The longing for a lively city with functioning public space will continue to exist in the future. Due to digitalisation and the processes of change associated with it, we have the opportunity to translate this longing into something concrete, and thus to create vibrant urban life. And because you just mentioned big cities: The concepts developed for smaller cities will play a decisive role here. That's where it'll get really exciting! What's important to me, however, is that the changes now occurring are opening up great opportunities for us. And we can and must encourage cities to take advantage of this. Cities therefore need to determine their DNA for themselves and become first movers. This requires courage and often doesn't really fit in with our current political processes, but you also have to think outside the box!