SUSTAINABILITY

Three times simple

Three research buildings completed in Bad Aibling in 2020 that are part of a research project initiated by TUM, the Technical University of Munich, have now made the shortlist for the DAM Awards. The project, involving several different departments in the Faculty of Architecture, is investigating the question of how to approach planning building processes, a task that is becoming increasingly complicated. Their answer goes by the name of "Building Simply" and is intended as an alternative to current developments.

Alexander Russ: What does "Building Simply" mean?

Florian Nagler: To tell the truth the question is not that easy to answer. Architects don’t see such things quite the same way as do the tradespeople. However, what we mean by the term is that we have noticed over recent decades that building standards are getting higher and our answers correspondingly more and more complex. This is making planning so complicated that we are not always able to deal with the associated processes and results – and by this, I mean not only the planners but also the companies carrying out the work and the ultimate users of the finished building.

You have now demonstrated in the form of your three research buildings in Bad Aibling that things can also be done differently. What is the project all about?

Florian Nagler: The undertaking is a multiple-stage research project at TUM in Munich. As a first step, we used various spatial models to investigate the possible appearance of a simple house that would not heat up unnecessarily in the summer, would require little energy to heat it in the winter, and would work well independent of users. With this in mind, we also devised a guide to building simply, one aimed at architects and clients and explaining the basic principles behind the concept.

What are these basic principles?

Florian Nagler: They include, among other things, using the right single-layer wall and ceiling constructions, avoiding ancillary materials or special components made of different things, consistently keeping the building separate from its technical systems, making use of climate inertia by using components with a high thermal mass and appropriate expanses of windows that require no further protection from the sun. However, it would be a pity if the outcome was no more than a project report with the relevant results, the kind of thing that is destined to end up disappearing into some drawer or other. This is why we looked for somebody who was prepared to build real houses for us that would demonstrate everything by creating a real-life example.

And in the form of B&O Gruppe, a technical service provider from Bad Aibling, you really did find a developer in the housing sector.

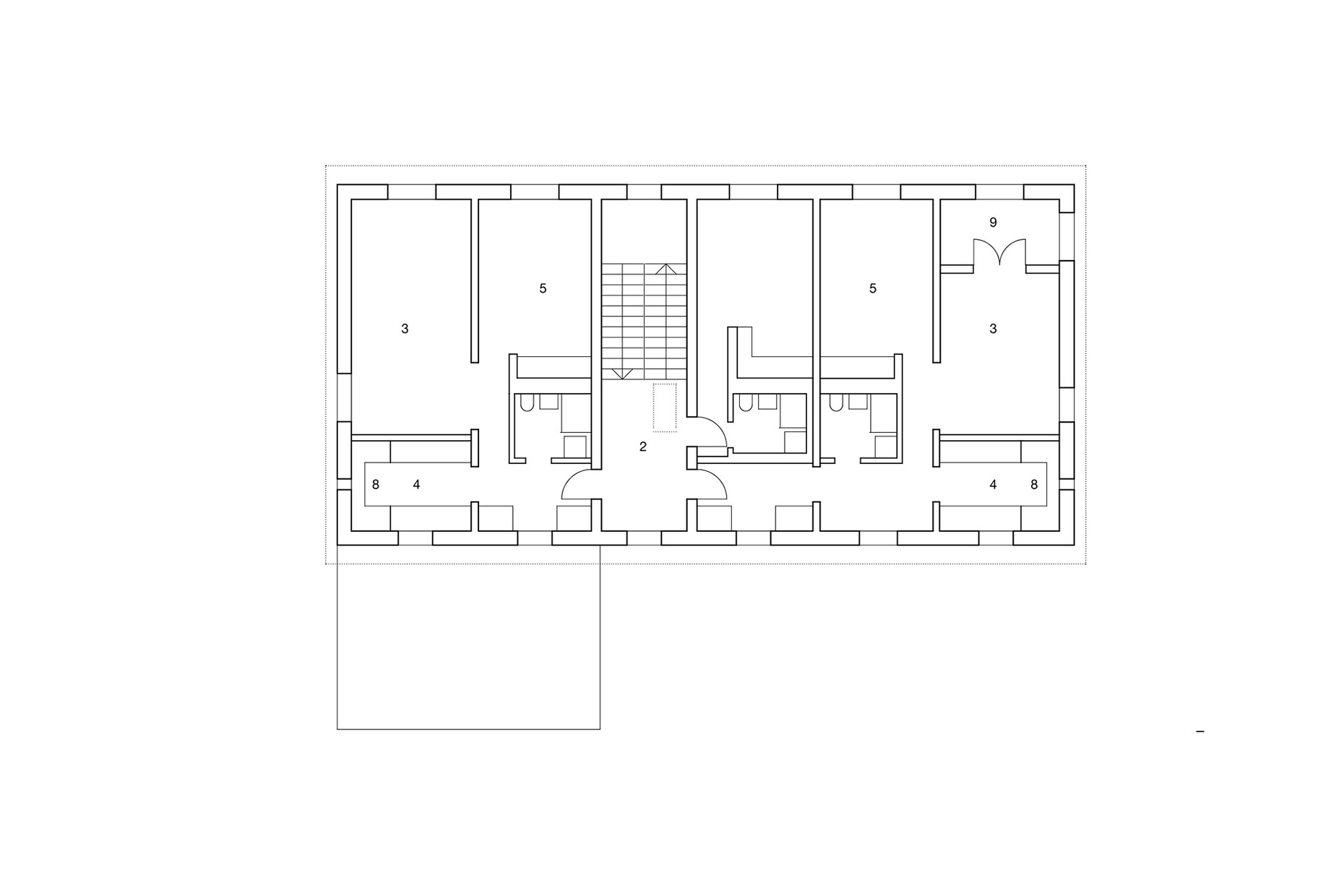

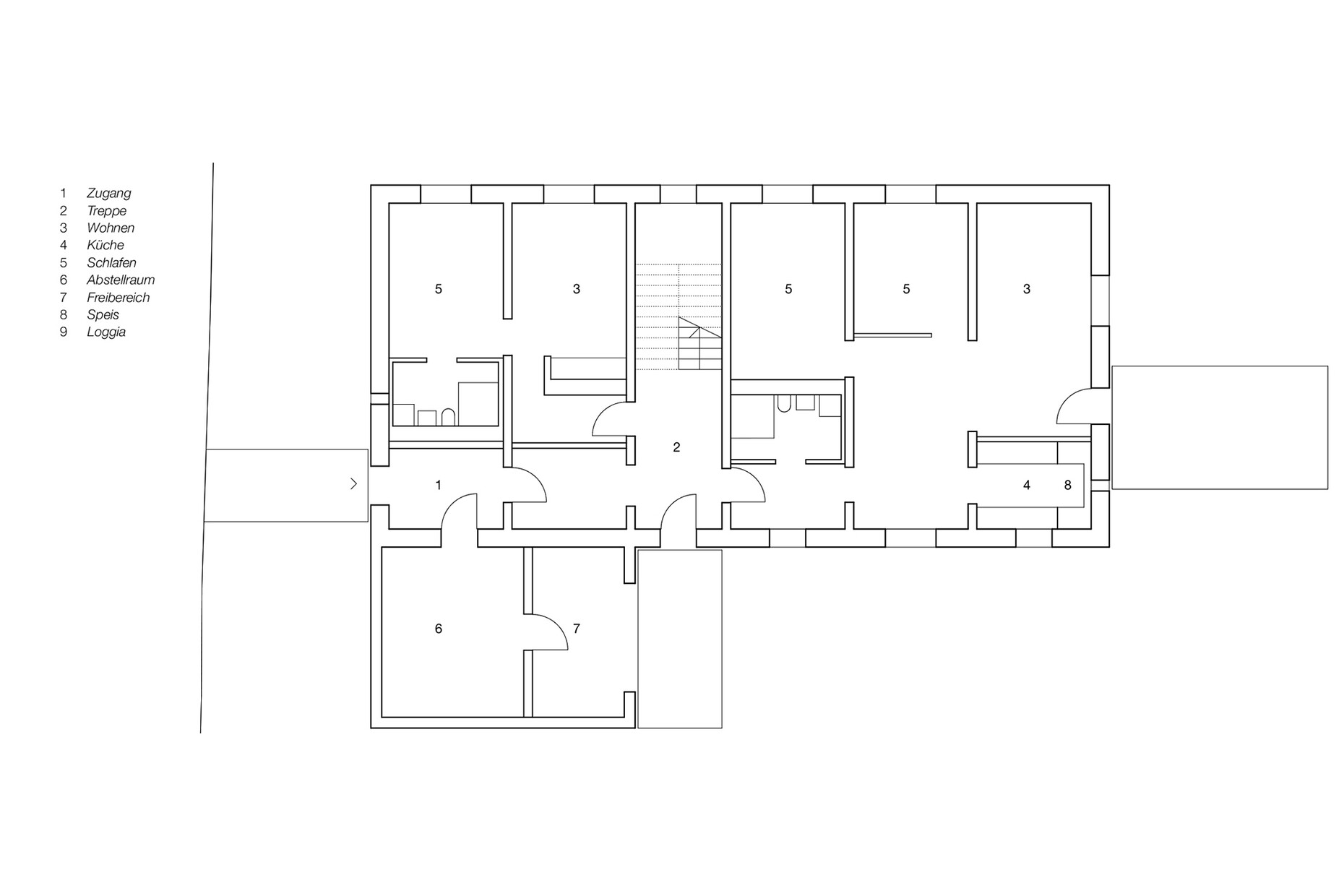

Florian Nagler: Yes, I already knew B&O Gruppe through a joint project to erect a building on top of a parking facility in Munich, a project I was able to realize with my own architecture practice – it was a low-cost residential building using a prefabricated wooden structure. We then implemented the three research buildings in Bad Aibling with monolithic wall constructions, one of which is made completely of wood, one of masonry, and one of lightweight concrete.

This means that the walls do not require any additional insulation. This kind of thing will not necessarily fill all the manufacturers with enthusiasm. How is it going to be possible to get the industry to implement your ideas about building simply?

Florian Nagler: Of course, our choice of products and their gray energy were a factor, but at the end of the day, our aim was not to show anybody up or to demonstrate that some products are worse than others. As planners, we were just fed up with having to plan such things as building envelopes boasting 11 layers, each one of which possesses its own potential for error. That is why we wanted to demonstrate that things can be easier. In the process, we opted for the most prevalent materials used in housing construction – and those were, when all is said and done, masonry, wood, and concrete.

How did your limited choice of materials affect the construction process as such?

Florian Nagler: At our building site in Bad Aibling the masonry house, for example, used only one type of masonry, a kind that could be divided up into four parts and also used as window arches. At the end of the day, this makes the whole thing much easier for the people actually building the house. And to be quite honest, there are never that many qualified tradespeople on building sites. Most of them are neither skilled carpenters nor real bricklayers, but in fact probably butchers or bakers. That’s the situation in the real world and of course it then helps if the processes are not overly complicated.

You are also looking into the subject as a group of architects and engineers. What does that involve?

Florian Nagler: Several of the departments at TUM in Munich teamed up for the research project. Alongside my own Chair of Architectural Design and Construction, there is also Thomas Auer’s Chair of Building Technology and Climate Responsive Design, Stefan Winter’s Chair of Timber Structures and Building Construction, and Christoph Gehlen’s Chair of Materials Science and Testing. Each department is responsible for certain functions. Thomas Auer’s team came up with the measurement concept with which we have been evaluating the research buildings since the beginning of the year. Of course, there are now people living in the houses. However, we have kept a one-room apartment in each house free for measuring purposes. The idea behind this is to measure the building’s indoor temperature, its energy consumption, and the energy input patterns over a period of two years, and then draw the appropriate conclusions.

Does your approach, the idea of building simply extend beyond mere materiality? What role is played by a building’s shape and its layout?

Florian Nagler: The two play an extremely important role. In my opinion, you have reached a dead end when you try to solve challenges in terms of climate or structural design using just building technology. There are very simple solutions to such challenges, solutions which have been tried and tested over a period of centuries, and it would be no real problem for us to revert to them. Examples might be projecting roofs or windows with deep, overhanging eaves, which keep the sun out. Such things make a very great contribution. However, such elements have been eliminated from the canon of modern architecture. Nevertheless, these are elements that use the architect’s tools to respond to climatic and meteorological circumstances.

What we are talking about here is regional building versus Modernism as a universal style of architecture. How exactly do your colleagues react when you suddenly start incorporating gabled roofs, visible downspouts, and round-arched windows into your architecture once again?

Florian Nagler: So far, my colleagues have been very open to it and many of them felt that it was like a breath of fresh air to be able to get away from certain formal conventions. Incidentally, we are not aiming at any particular kind of look whereby gabled roofs are part of some minimalist primitive hut. Buildings with an archaic feel, of the kind that were in vogue for a time, have nothing in common with building simply – quite the reverse, in fact. With the former the rain gutter is not visible but is integrated into the building shell, which involves time and money. With us, the rain gutter and the downpipe have been visibly attached to the building, as this is a simple, tried-and-tested solution. In other words, building simply doesn’t mean that the architecture should end up looking simple, but that it really is simple to construct. However, it has the potential to become a form of architectural expression in its own right.

To what extent does the increasing number of norms and building laws hamper building simply?

Florian Nagler: To tell the truth, when we embarked on the research project, we thought we would have to apply for any number of special permits, but at the end of the day the buildings we erected complied with the building regulations and the other relevant laws, such as those governing heat insulation. Of course, they are not energy-plus buildings. However, looking at a lifespan of 100 years, it becomes clear that they can very much keep up with an energy-plus building – at least, if you really do include everything in the equation. After all, an energy-plus building also needs a certain amount of building equipment and appliances, the kind of thing that needs to be replaced repeatedly – and everything that has to be built into a house can break down. This is why our simple yet robust buildings certainly are capable of holding their own against the competitors.

You are currently planning your subsequent project – some research buildings in Garching. What is your approach in the latter case?

Florian Nagler: What we are currently planning is three halls of residence for the student services on the TUM campus in Garching. The approach is basically the same as the one for the research buildings in Bad Aibling, except that what we are talking about here is a different grade of buildings, one with four stories, i.e., something on a larger scale. Here, we would like to come as close as possible to a zero-energy house. When examples of such houses have actually been built, the subject will have a completely different degree of visibility. And the response to the first three buildings was overwhelming – from pure feedback or inquiries to requests to build other houses just like it. This allowed us to see clearly that there are a large number of planners and developers who are thinking about that same subject.