Pillars and Arches Devoted to Rugby

As anybody who has watched a game of rugby live – or on TV – knows, this is an extremely vigorous sport. Its commonest form involves 15 players from each side coming face-to-face. And, when play is resumed after interruptions, for example, the term face-to-face is meant quite literally. With scrums, almost all the players in the two teams stand facing one another and attempt, in precise formations and arrangements, to push and shove their own hooker into a position where he can secure the egg-shaped ball for his own team. The line-out is the same kind of situation where two sides come together in an energy-laden encounter – the ball is thrown into a line-out from the sideline and the players try to grab hold of it for their respective team. In such situations, the catcher is lifted up to a dizzying height.

There is a quotation ascribed to Oscar Wilde that goes: “Rugby is a game for barbarians played by gentlemen. Football is a game for gentlemen played by barbarians.” This is, in part, a reference to the fact that in many parts of the world rugby is a sport still played by the upper classes today. This is not the case in Ireland, where rugby is popular beyond all the boundaries imposed by the different socio-economic groups. In Limerick, where the Shannon, Ireland’s greatest river, prepares to spill out into the Atlantic, a building has just been completed that attempts to translate this particular moment in a game of rugby into architecture. Completely financed by a nonprofit foundation established by Limerick-born businessman John Patrick McManus, this edifice, costing 19.5 million euros (17.3 million Pound) was designed by Níall McLaughlin Architects.

With his design by the name of “The Rugby Experience”, McLaughlin, an Irish architect who trained in Dublin but now operates from London, is continuing with a series of noteworthy projects that not only investigate traditional architecture-related topoi, but that also feature materials that have been assembled precisely and with a craftsman’s skill. In 2021, for instance, the practice completed the new library at Magdalene College, its row of detached houses featuring gables facing the street plus chimney stacks ideally complement Cambridge’s historical college buildings. The buildings for Balliol College in Oxford also blend in with their long-established surroundings in the latter university town in an equally appropriate manner.

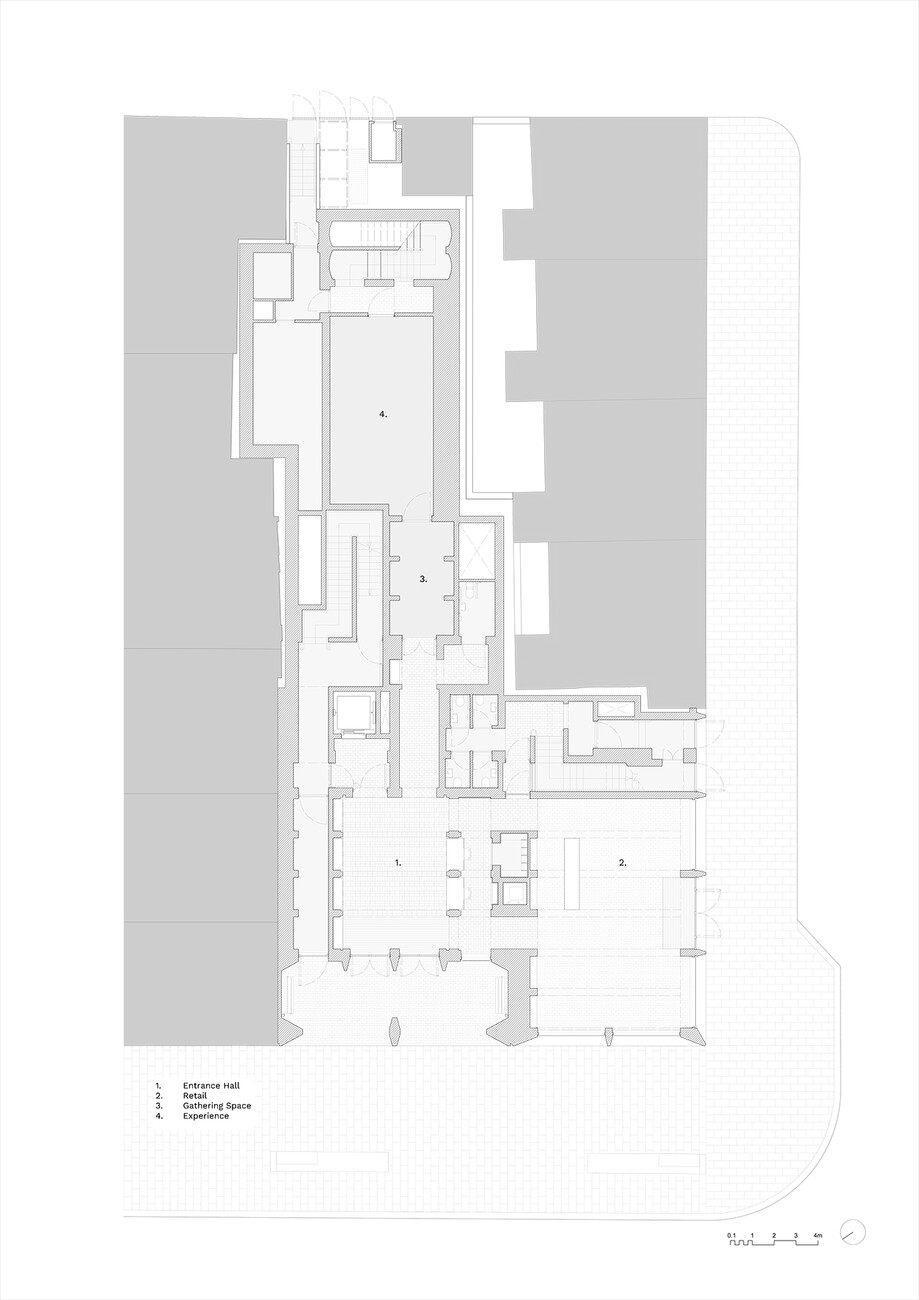

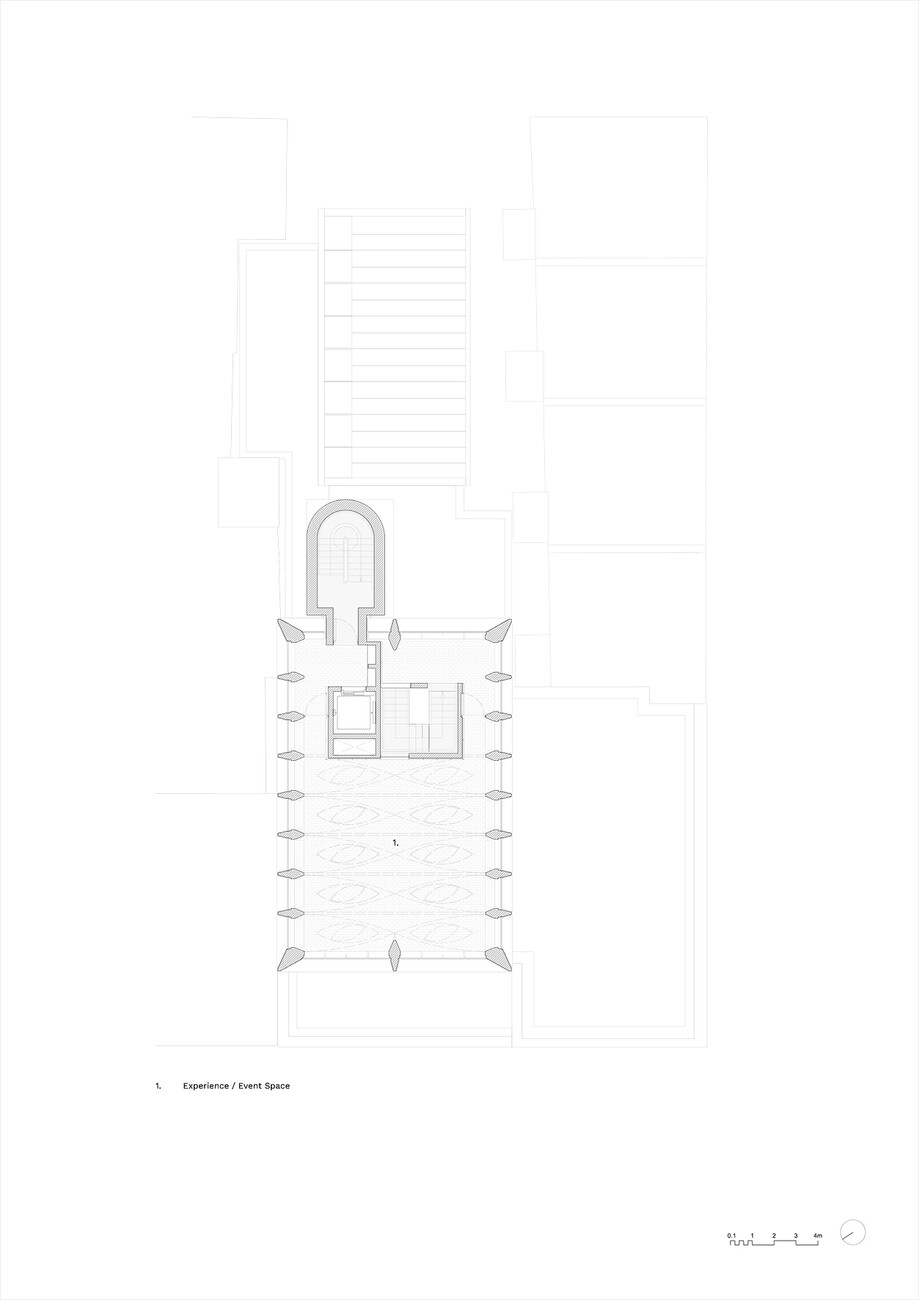

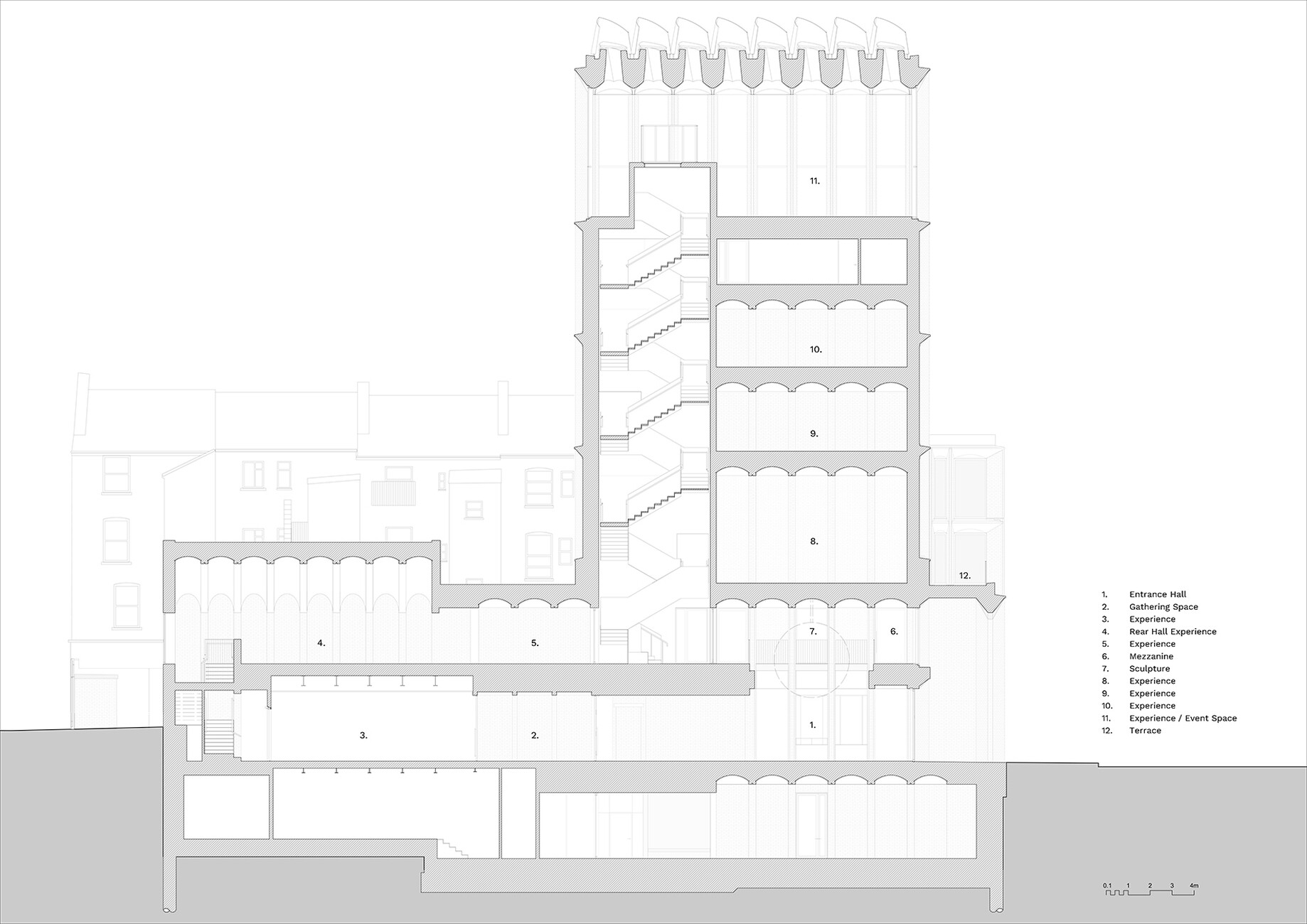

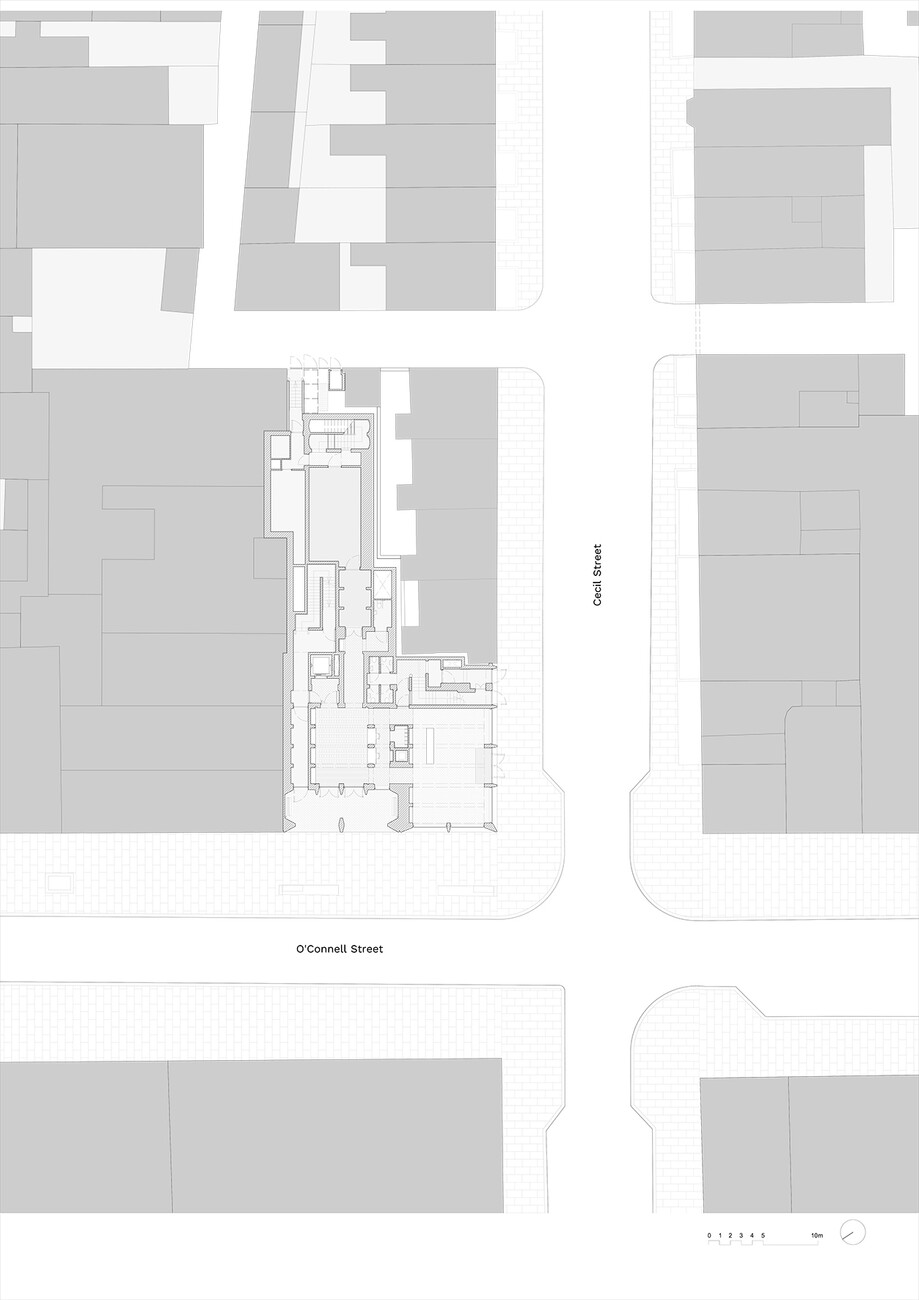

In Limerick Níall McLaughlin Architects have lent the energy of a game of rugby concrete dimensions in space – and this right in the heart of the main shopping street in the latter 57,000-resident city. Just like so many other downtowns, Limerick is a clear indication of how the retail industry has undergone a transformation. And this new build stretches up on the corner of O’Connell and Cecil Street, only two blocks away from the banks of the Shannon. Its scheduled functions – not only to serve as a monument to sport but also to breathe new life into the entire city center and to provide the local rugby community with a home before and after the matches played by their team, “Munster Rugby”. The plan is for the supporters of this club, martially known as “The Red Army”, to have the opportunity to meet up for a few (dozen) cold beverages before the games and then to sally forth together in the direction of Thomond Park, located two km away, where the club holds some of its home matches. One idea is for local products to be on sale at a shop there. Another is for the premises to include rooms that can be hired out to any of the city’s residents for functions – weddings and suchlike. All of these elements will be pulled together by an exhibition devised by London-based agency “Event" and covering various aspects of sport itself. The exhibition will wind its way through the building, looking at the subject of passion, discipline, integrity, solidarity and respect.

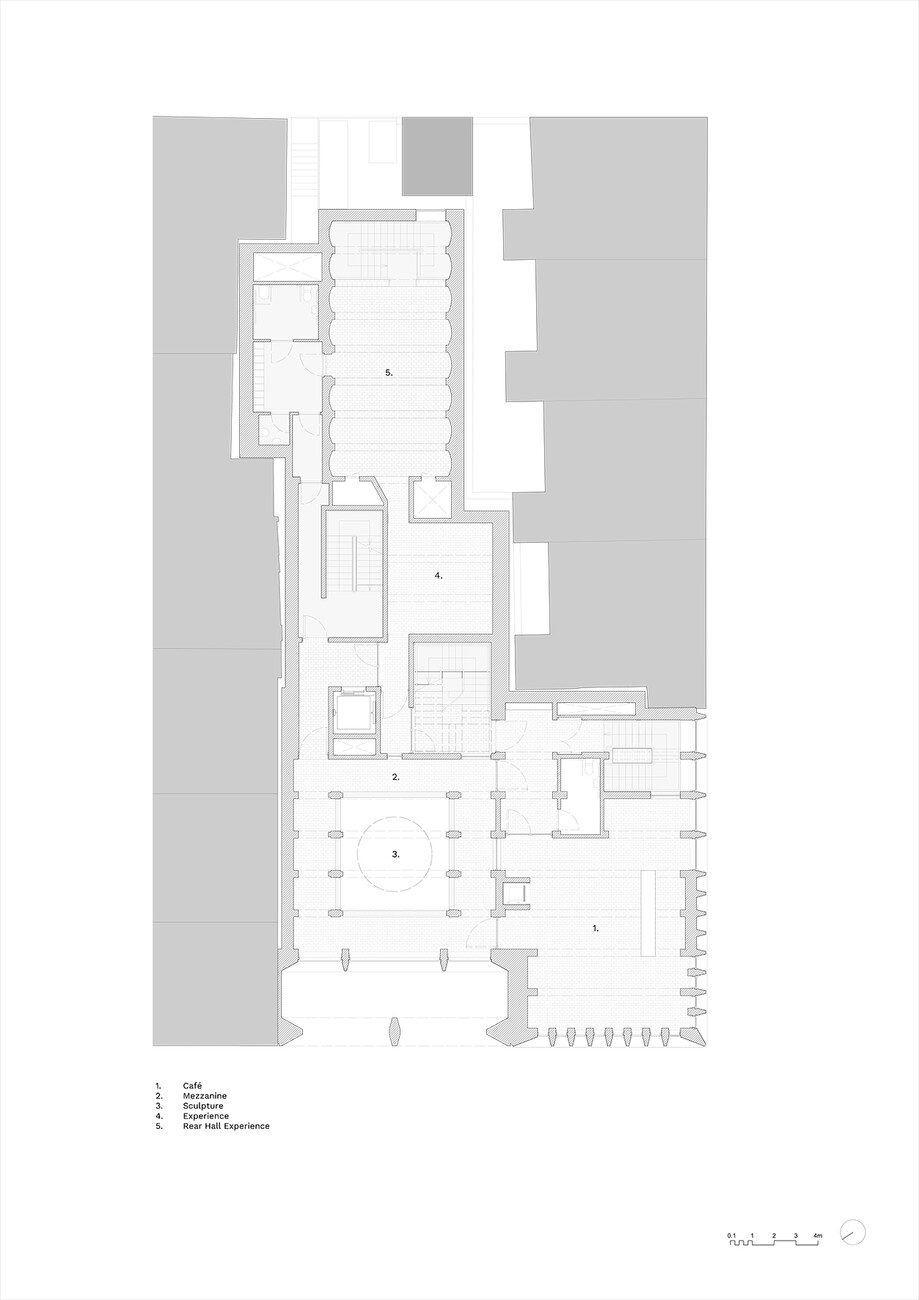

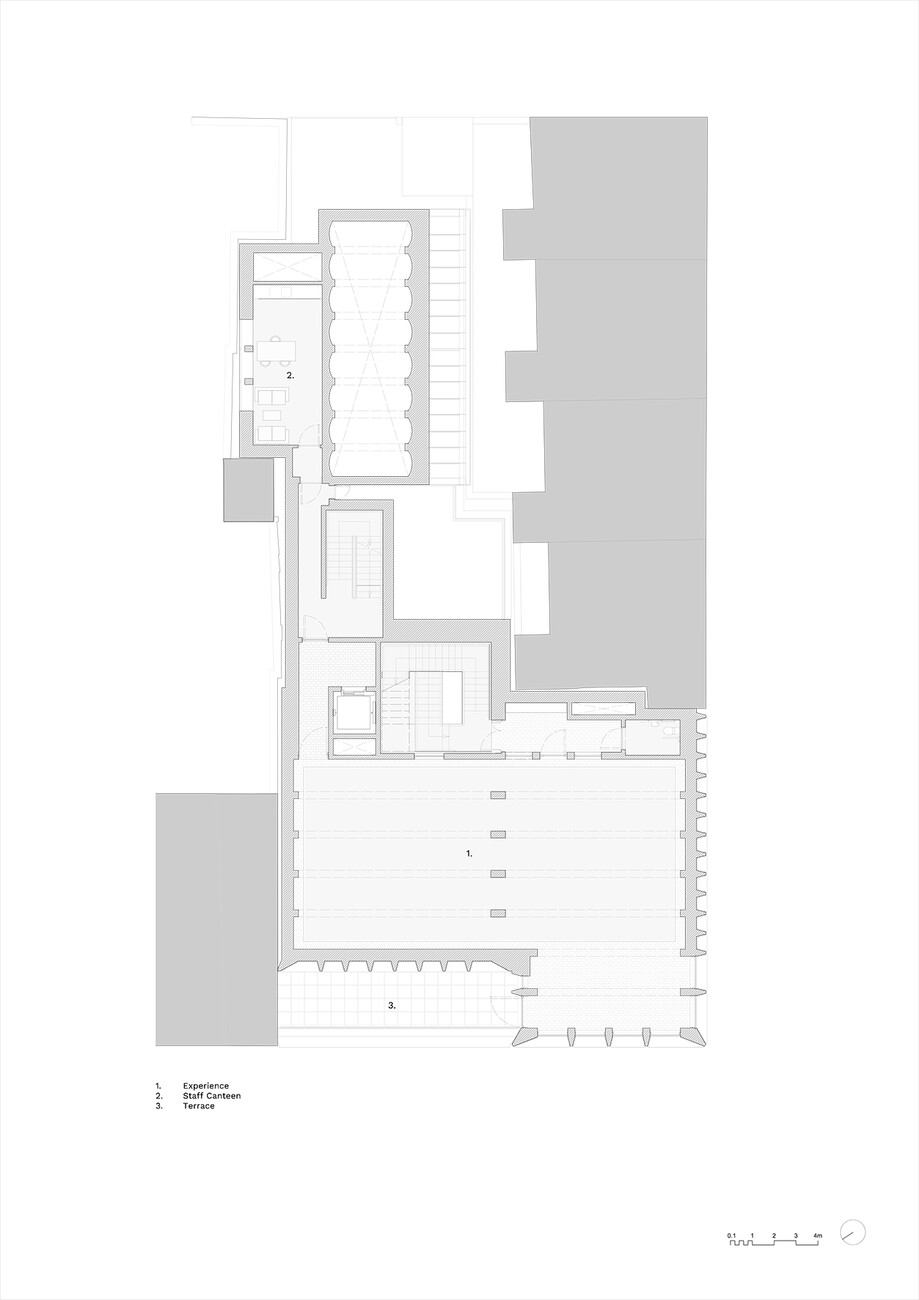

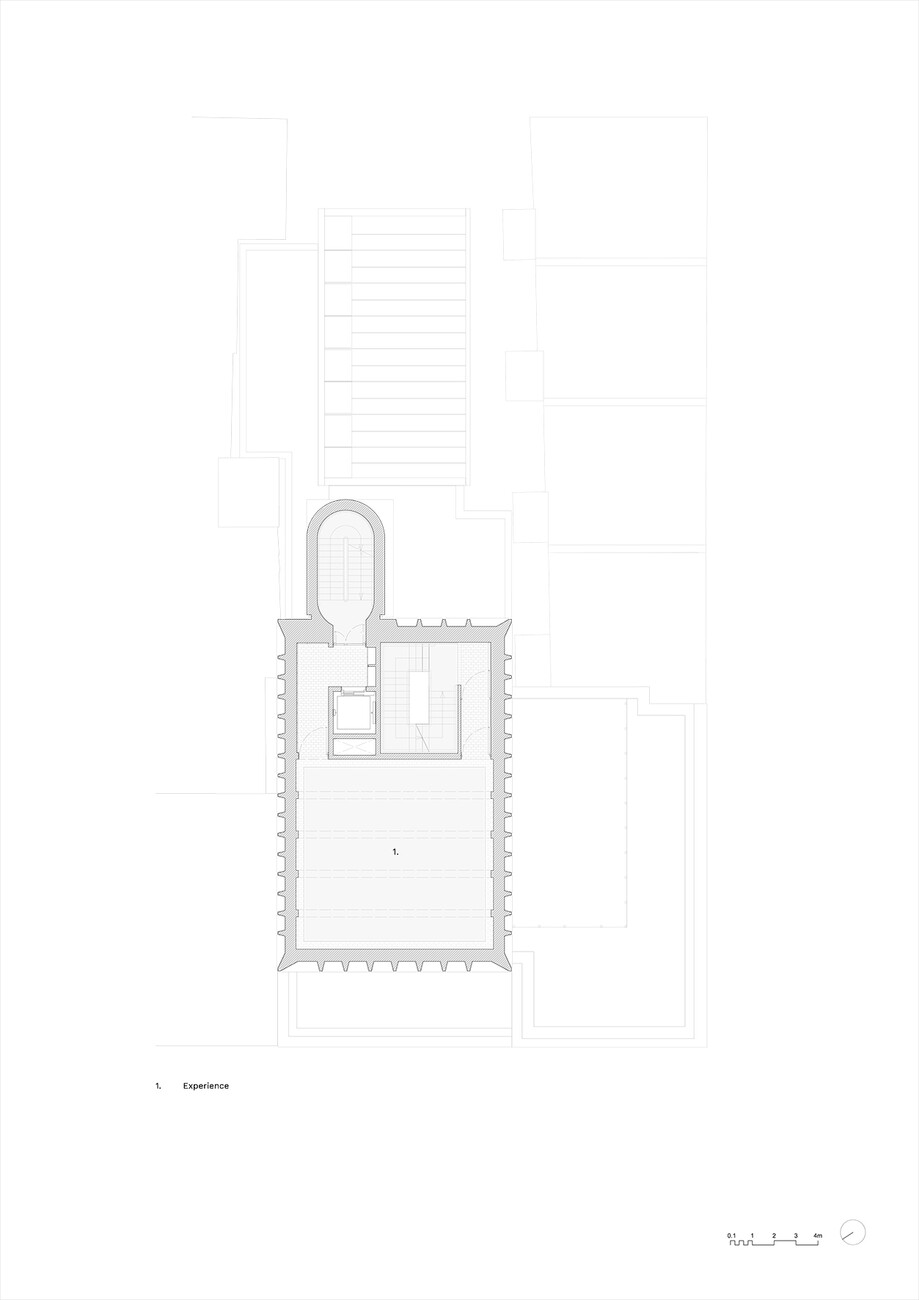

Indeed, the building’s interior is well-nigh labyrinthine. On the outside, it continues the eaves height of the 4-5 story neighboring building and their brick façades, a characteristic feature of the city. Setback stories of differing heights, sometimes opened up by windows, sometimes closed off by brickwork, are structured vertically by means of tapering pillars and pilasters, and horizontally bordered by delicately placed segments of arches made from prefabricated concrete parts. On the O’Connell Street side, the northern half of the edifice is set back as of its second floor, thus forming a kind of urban balcony – as if it had been purpose-built for fans to show off any trophies they may have acquired. Behind this a tower rises up, one that is significantly higher than most of the surrounding buildings and is crowned by a story spanning two floors and glazed on three sides. This story towers over the city like a piano nobile. The corner of the building, in turn, maintains the block’s eaves height, defining the street area in its own right. The building mass makes for a genuine, authentic feel, just like the bodies of the players during a line-out.

The interior of the building is equally down-to-earth in approach. Níall McLaughlin views the latter as the indoor staging of a play or a short story. Rooms are arranged in upward sequence like individual episodes. Dark areas are followed by lighter ones, there are repeated obviously staged vistas over the next area or out over the street. Here, areas that are partly used for virtual realities alternate with rooms that are seemingly entirely devoted to the brick aesthetics of old Georgian Limerick. This is most impressively demonstrated in the entrance hall, the back hall, which tapers upwards under vaulted ceilings, and at the top of the sequence of rooms decorated with brick and fair-faced concrete which surveys the roofs of the city. Here, the construction is shaped by its materials, their decisive shape rendering space itself tangible. And it thus becomes apparent why this building can do more, in formal terms, than its neighbors – after all, its rooms have something to offer the community. The piano nobile is not only part of the exhibition, it can also be used for weddings and private functions. With its urban balcony, the building can serve as the kind of setting in front of which fans and the local team can meet up and celebrate together. Anybody familiar with the sports museums and what is known as their “fan worlds” can only gaze enviously in the direction of Limerick.