Fox tossing, octopus wrestling and other madness

No sports! Anyone who has hitherto felt Winston Churchill’s insistence that physical exercise be avoided at all cost was the quirk of a cigar smoker who was as clever as he was melancholic will probably sit up straight in his tracksuit after reading Edward Brooke-Hitching’s “Fox tossing, octopus wrestling and other forgotten sports” and ask, unsettled: So what actually constitutes a sport? Much of what has existed down through the centuries by way of activity and entertainment and which from today’s viewpoint can be rightly or wrongly termed a “sport” proves to be so utterly brutal, dangerous or risible that you simply cannot believe it existed and start worrying about how humankind can be so irrational. And if your read the detailed and superbly researched entries here, you will often find the tears streaming down your cheeks, either from laughing or in disgust.

Take, for example, the custom of tossing people into the air with a blanket. Or the tortoise races practiced in the early 20th century in pubs in south Dorset – competitor Herbert was trained by the owner’s son singing to him, whereas Tischy really got going is his owner enticing him along with a piece of bread coated in marmalade. Or there’s the popular 1950s pastime of “telephone box squashing”, which the Americans adopted as “phone booth stuffing”, or the mass spectacles such as the “naumachiae” – huge replays of famous sea battles performed in flooded Roman arenas presumably as early as the 3rd century B.C. A trend sport among rival colleges was for a time “goldfish swallowing” (just to show those Harvard boys that they’re weaklings), not to mention those diehards who in the 19th century loved “waterfall-riding” on barrels.

Is all that really sports? The word “sport” was actually understood for centuries to simply mean any form of active pastime that was fun. The author quotes from Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary, where sport is defined as “play, diversion, game; frolick and tumultuous merriment” and in an alternative entry as “diversion of the field”, which included “fowling, hunting, fishing”.

You may not believe it, but this book collects, describes and explains not only many a strange, more or less enjoyable pursuit, but is also a veritable manual on the power of the Enlightenment, the strange paths history takes, and the blind spots in officious historiography. One example shows this with great clarity: Anyone who is today surprised by what football hooligans are capable of should simply look back at the history of the game, which started with “Mob Football”. It is no coincidence that in England the early versions of football (and other games) were frequently prohibited by the powers that be because they feared these might keep people from pursuing militarily useful activities such as archery or sword-fighting. For example, a decree in 1363 stated: “We ordain that you prohibit under penalty of imprisonment all and sundry from such stone, wood and iron throwing; handball, football or hockey; coursing and cockfighting, or other such idle games.”

Needless to say, in order to simply get out a kick a pig’s bladder filled with air around at any opportunity, not only the laws and church rules, such as were intended to protect excessive exertion on the day of rest, got ignored, but the activities were intensified such that for a game of football entire villages competed against each other, and had to try and get the ball into the graveyard of the opposing village to score a goal. This diversion was very violent: damage to property, injuries, even fatalities were a matter of course. Puritan writer Philip Stubbs thus raged in 1583 against the brutality of ball games as follows: “Sometimes their necks are broken, sometimes their backs, sometimes their arms, sometimes one part is thrust out of joint, sometimes the noses gush out with blood... Football encourages envy and hatred… sometimes fighting, murder and a great loss of blood.” The author adds: “Little changes.” The later insistence on fairness would thus appear in a quite different light.

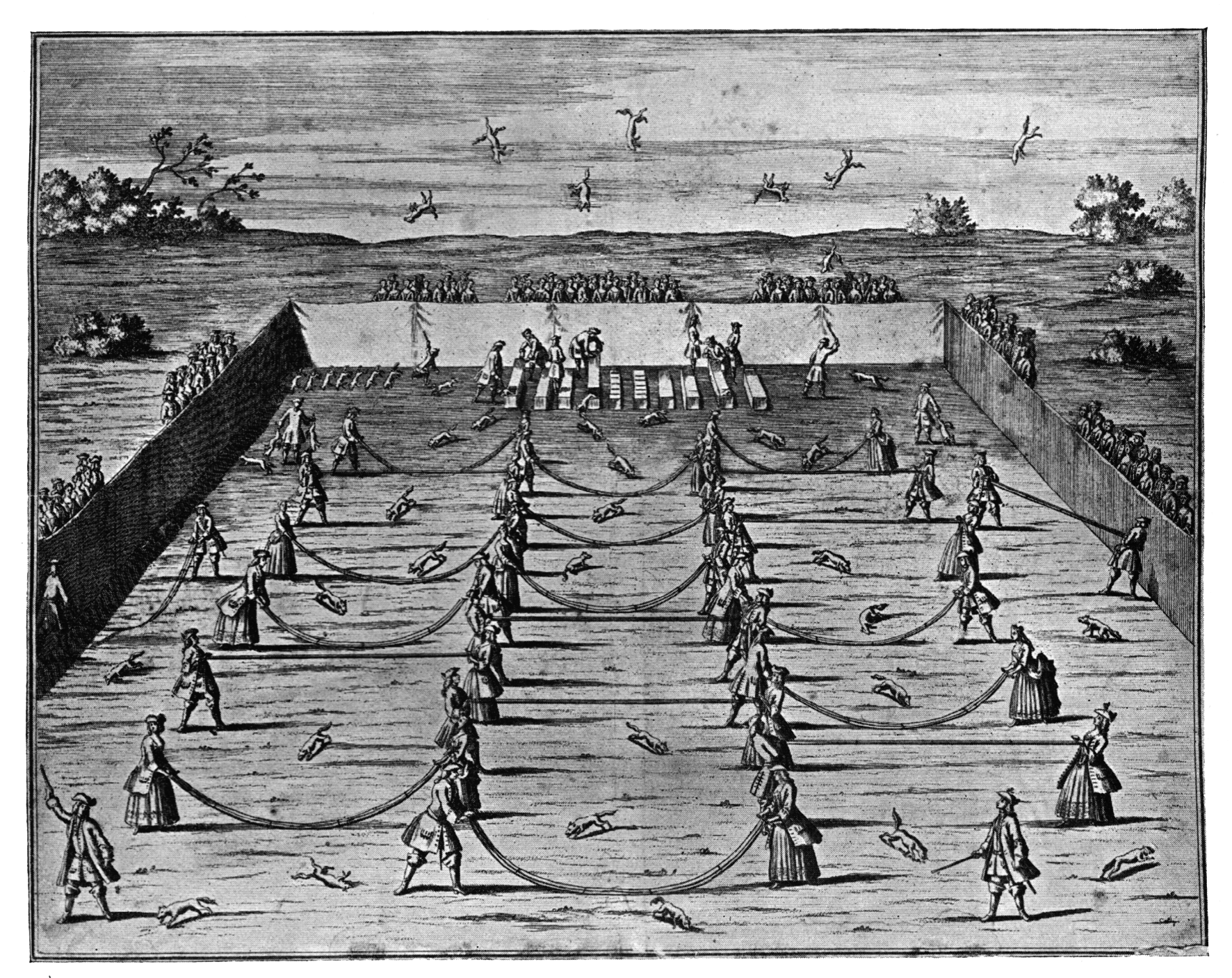

In his introduction, Brooke-Hitching explains not only how he came across a leisure pastime called “fox tossing” in an 18th century German book in the form of a puzzling illustration, where “well-dressed nobles (were) casually slinging the splay-legged creatures heavenwards,” but also how he realized that it had to be a sport that “seemed to have slipped through the net of mainstream historical record and yet is one of the most fascinatingly eccentric aspects of Teutonic hunting history.”. “The fact,” Brooke-Hitching continues, “that ‘Fuchsprellen’ has maintained such a low profile over the years begged the question: how many other sports like this have been forgotten?” In his repeatedly astonishing book he therefore sets out to explore the “hidden pockets of history to find the answers.”

The entries draw on a broad variety of sources, from Suetonius to Shakespeare, from the Icelandic sagas to 14th-century Florentine manuscripts. The author discerns essentially three reasons why with the benefit of hindsight often seemingly strange sports have ceased to be attractive and got forgotten: cruelty, danger and ridiculousness. With the largest role played by senseless cruelty, above all to animals in sports such as eel-pulling, pig-sticking or ratting, bear or lion-baiting.

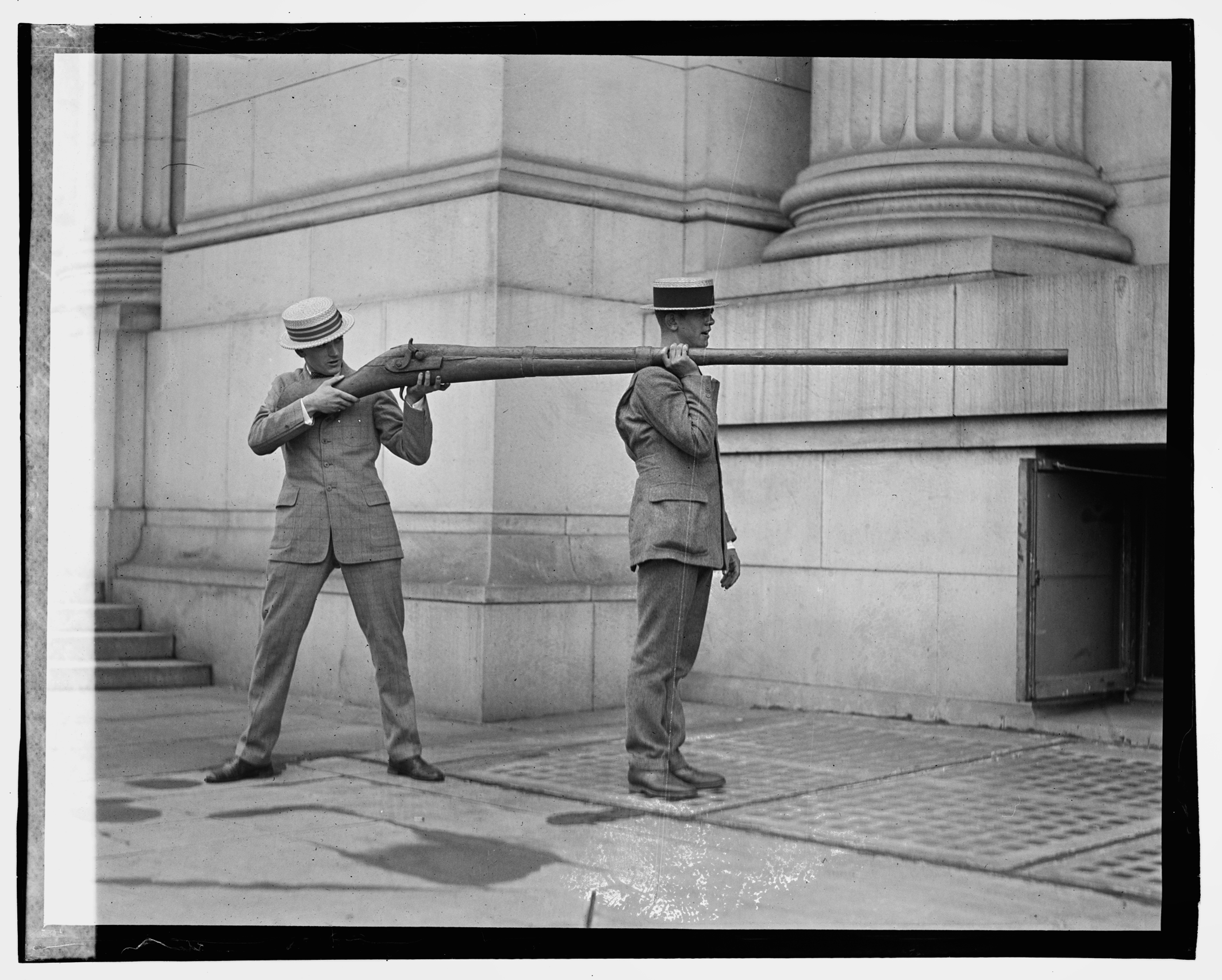

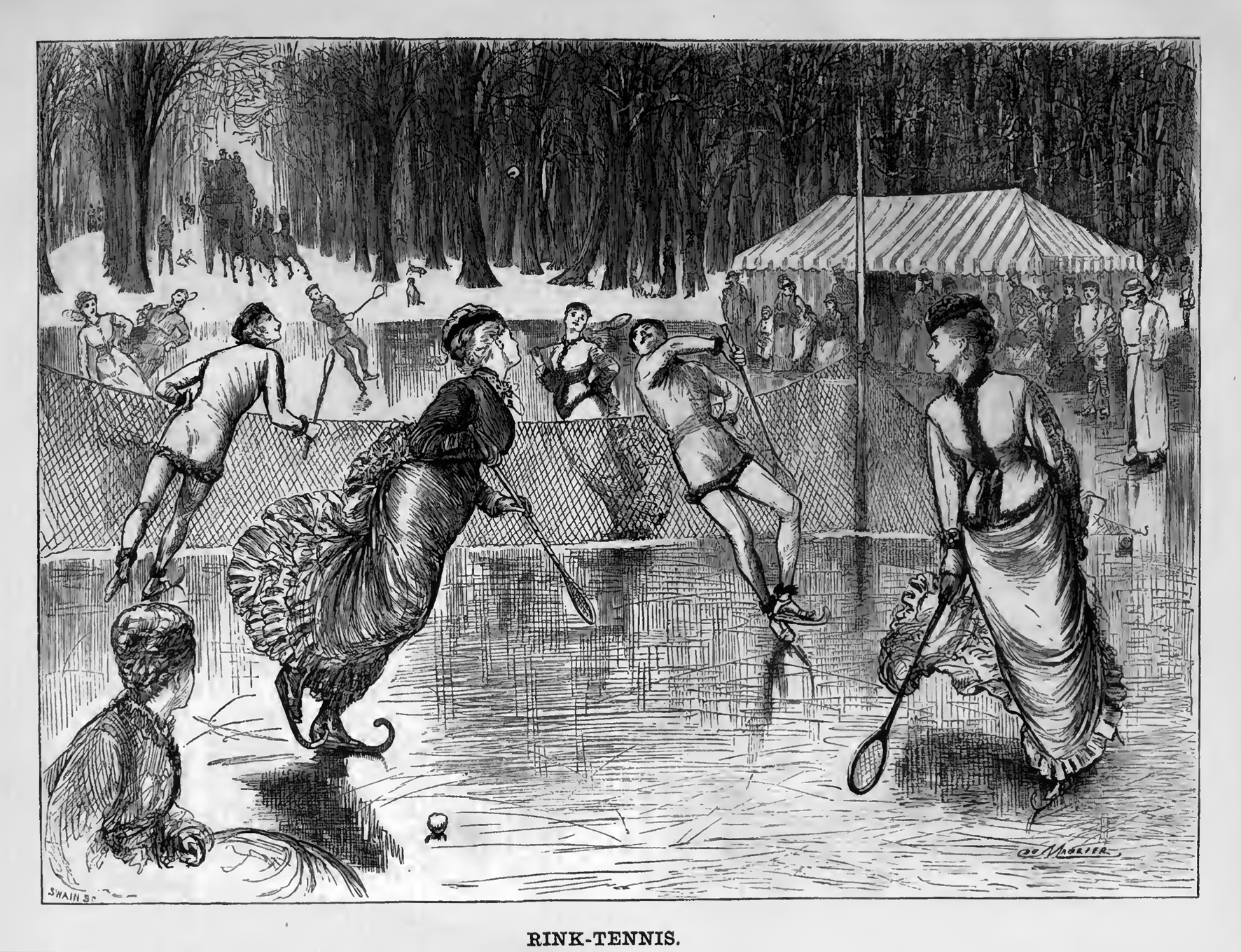

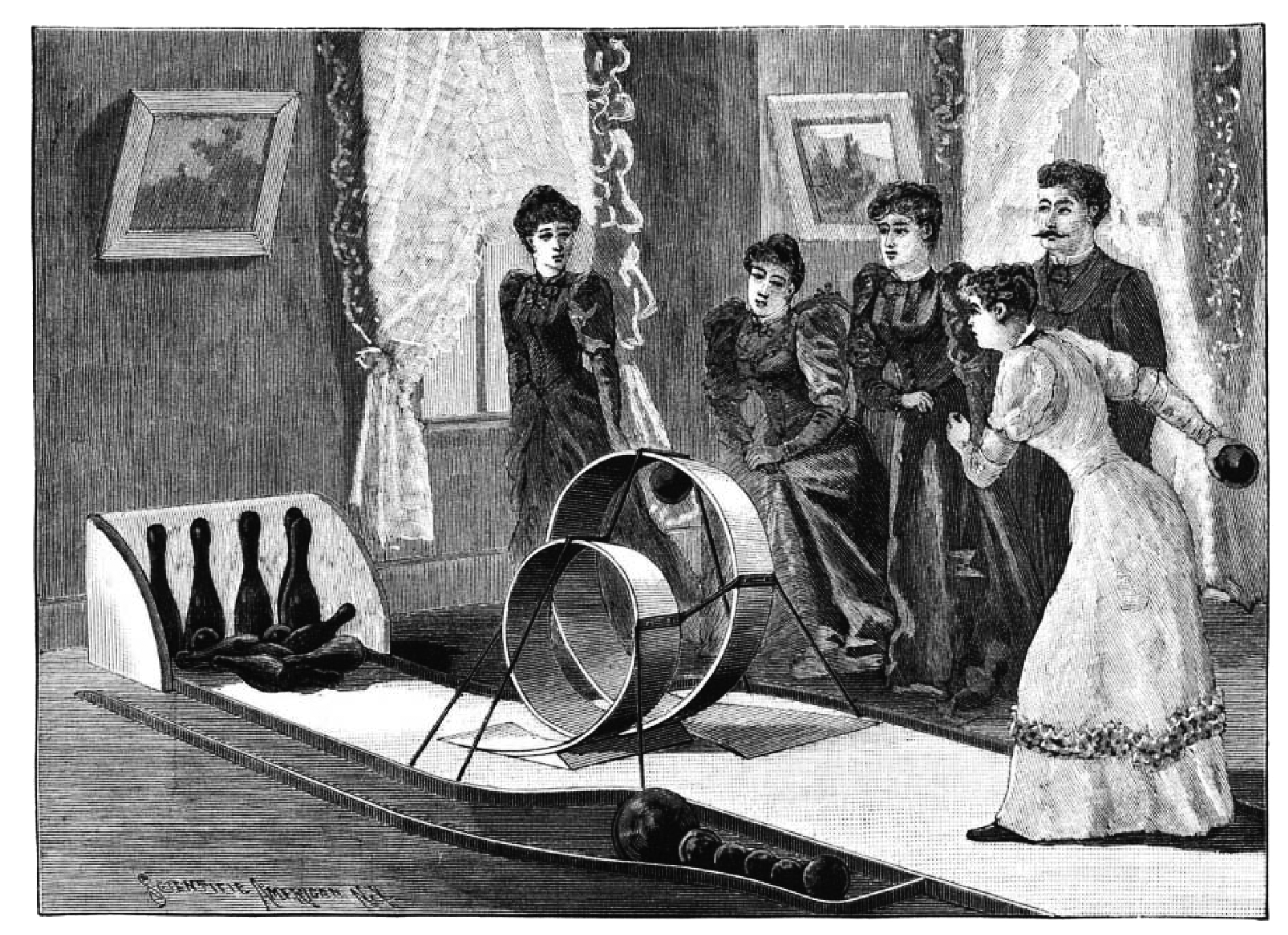

Alongside sports that seem to have been invented specifically in order to damage the human spine such as “barrel-jumping” or dangerous variants such as Auto Polo or Balloon Jumping (clearly an early form of paragliding), there were any number of fairground games, such as Hot Hasty Pudding Eating or Jingling. Not to forget the dwarf- and then chicken-chucking on Frankfurt’s Bernemer fairground. And the book narrates what was behind “Chunkey”, the ur-American, and why Ice Tennis was so popular in New York in 1912.

Popular in Norfolk in the 1960s, Dwile Flonking must have been especially amusing: to the sound of an accordion people danced, whereby the “flonker” armed with a “driveller” (a broomstick to which a rag drenched with beer was attached) slowly rotated in the opposite direction to the dancers, and (often with his eyes bound) the moment the music stopped tried to hit the dancers closest to him with the rag. A face hit was worth three points, two for the upper body and one for a hit between knee and hip. Every “flonker” had two tries per round; if he missed, he had to “take the pot”, meaning drinking a large amount of beer from the “gazunder” (chamber pot), while the dancers sung “The Dwile Flonkers Lament”. A player was docked a point if still sober at the end of the game.

At the end of the day, only one thing is certain when it comes to sport: Anyone who has read this book will no longer be baffled by the bizarre stunts people still attempt for the Guinness Book of Records or the ghastly games in TV shows.

Edward Brooke-Hitching

Fox Tossing, Octopus Wrestling and Other Forgotten Sports

272 pages, paperback

Simon & Schuster, 2016

ISBN 978-1471148996