Back to Relevance

With regard to architecture, for a long time the Catalan capital was primarily known for its huge and arduous projects. As such, the city’s architectural history over the last 100 years is full of architectural icons for which space was somehow created in this densely built-up capital – from Gaudì’s Sagrada Familia via Mies‘ Barcelona pavilion, the extensive urban redevelopment for the 1992 Olympic Games, Richard Meier’s MACBA Museum (1999), Jean Nouvel’s Torre Agbar (2005) or Herzog & de Meuron’s strange blue triangle for the ambitious "Universal Forum of Cultures" (2004) which failed so spectacularly.

Yet these great efforts seemed just that: a little too strained to provide good architecture that would contribute to making Barcelona a livable city. And the economic crisis in 2008, which also hit the real-estate market, also put paid to these grand developments. Now the city is finally considering what is really important in terms of architectural development. The city administration itself initiated a turnaround a few years ago, the first fruits of which can now be seen. It is an astounding story to which two completely independent books are devoted, each in its own way.

Urban architecture and community since 2010

Recently, Munich publishing house "Detail" began to present a series dedicated to the latest architectural output in various European cities. Following on the heels of Copenhagen and Berlin, it is now Barcelona’s turn to be presented in detail by way of 30 projects. But anyone looking for new icons will be disappointed. Certainly, as long as iconic architecture is still regarded as meaning glittering, curving sculptures like Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. It is already evident from the titles of the book’s three chapters that the current trend in Barcelona is to realize architecture for the community and everyday life. The chapters are namely called "Community Spaces", "Culture and Education" and "At Home in the City". They feature sports complexes, civic centers, community centers and flower markets, schools, libraries and nurseries as well as small-scale housing projects for senior citizens, refugees, people on low incomes or cooperative housing models. If you were to combine these 30 projects to create one large panorama, the picture would be of a vibrant, livable city full of small-scale and modest buildings which are no longer aimed mainly at tourists – but at the local inhabitants.

Nonetheless, the architecture is spectacular and exciting. At first sight, the sports center in the Nou Barris district (masterminded by Anna Noguera and Javier Fernandez) is just a simple, rectangular box over which freshly planted climbing plants will soon have cast a dense net. Inside, however, you find a municipal swimming pool on top of which a sports hall has been stacked. This saves space, which is in such short supply in Barcelona, and creates a lively interaction between the local sports clubs. Or take the beautiful, slightly curving building which Benedetta Tagliabue designed for a cancer support foundation. With its brick facades into which large floral decorations have been inserted it could almost pass for an iconic building, if it did not merge so wonderfully inconspicuously into the grounds of the historic Sant Pau Hospital with its buildings in the Catalan Art Nouveau style.

New architecture first seen at second glance

Other changes are barely visible from the outside such as the civic center in the Montjuïc district, inserted by Harquitectes behind the facades of an old building from 1928. Just a few changes sufficed to transform a splendid primary school building from the 1950s into a library (Oliveras Boix Arquitectes), while the municipal film school EMAV and another library have been given a fitting new home in what was once a factory. Moreover, the new offshoot of the MUHBA municipal museum for which one might perhaps at one time have built a spectacular ostentatious architecture has been magnificently housed in a 100-year-old factory building. The conversion was supervised by local practice BAAS Arquitectura, who at least included a few additions and fixtures of gold-galvanized steel, making a tongue-in-cheek reference to the lavish icons of the more recent past which is both sturdy and inexpensive.

The fact that the 30 projects include many conversion projects resonates with the image of architecture designed to be economically and ecologically smart with an additional focus on the public domain and creating greater social value for the neighborhood. Existing buildings are no longer demolished to make way for something new and radical but rather the structures retained and then altered to suit a new purpose – creating the impression that this fresh architecture at the start of the 21st century had finally put an end to all the radical new beginnings which were proclaimed in the 20th century in ever new waves. Instead, contemporary architecture is happy to combine its strategies with pre-modern traditions, in which it was quite natural to build using what was available locally or was already there. This applies equally to conversions and new buildings, whereby the latter are often made of prefabricated modules of wood or concrete and combined with bricks and glass. After all, this revival of the pre-modern is not romantically motivated but pragmatic, although not spartan but at times luxurious, spacious, and cheerful. Even the arguments regarding sustainability which accompany every project in this book, by no means prohibit the use of any of these industrial materials; it is rather a matter of where they come from, what they are used for, and how they can be combined.

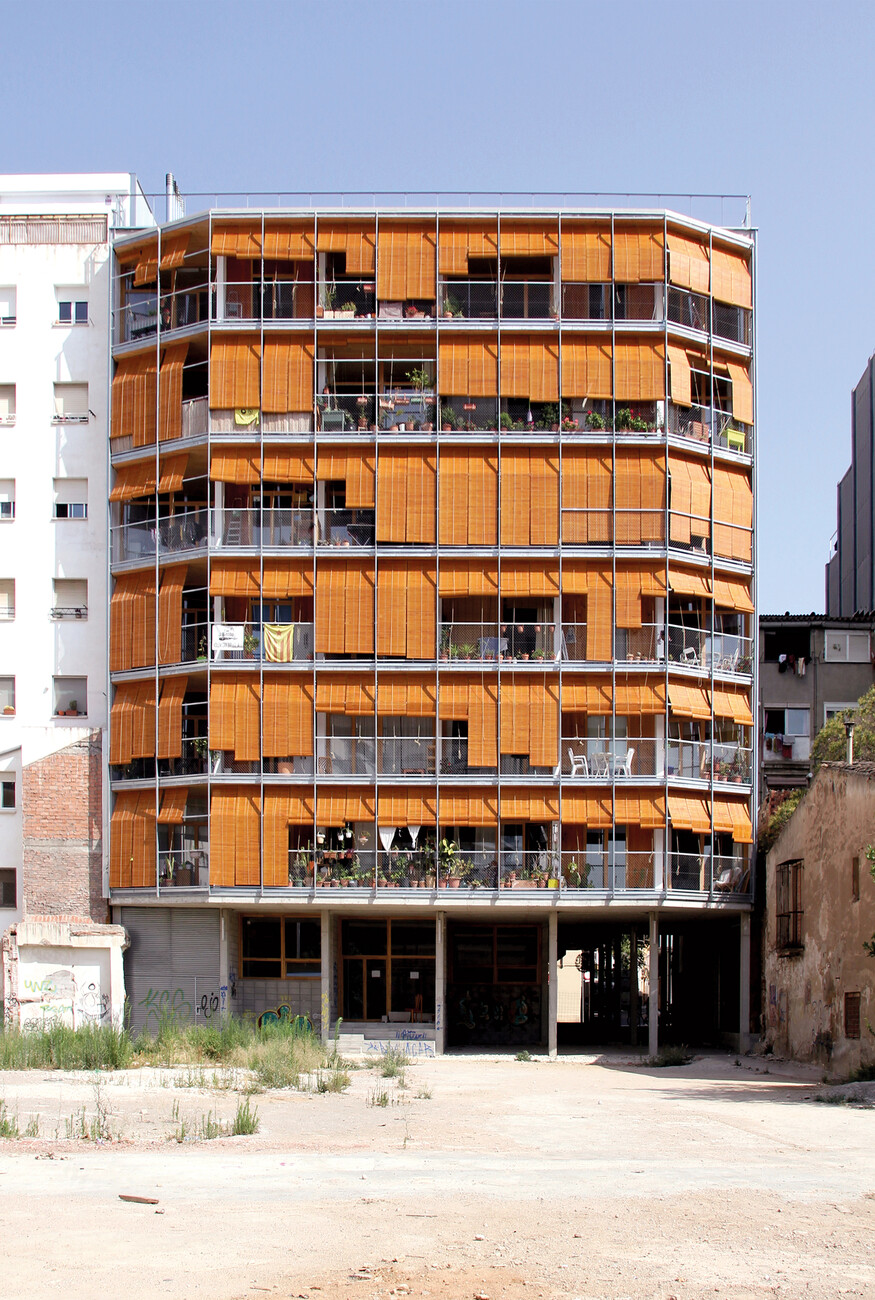

The surprising residential buildings in this book also stand for such ideologically unencumbered, innovative building – from the cooperative building La Borda (designed by architectural collective Lacol) via the wooden building for the housing cooperative La Balma (also by Lacol) or the 49 social housing units for single seniors in Eixample (Arquitectura Produccions, Pau Vidal and Vivas Arquitectos) through to the subsidized housing units on a narrow plot in the Gothic Quarter made from 12 discarded shipping containers (Strddle3, Eulia Arkitektura, Yaiza Terré). Here, each example seems more impressive than the next. Incidentally, it is striking that the architects organize themselves in collectives or in constantly changing work teams, but this fact is not addressed separately in the interviews and essays. What certainly does emerge from these 30 projects is that a Barcelona which is finally young again offers solutions and ideas that could be transferred to many other cities in Europe.

Architecture from/for the community

For anyone especially interested in this conspicuous boom of housing cooperatives in Barcelona and wanting to find out more, we strongly recommend a book that has just been published by Barcelona architectural publishing house Actar. The background to this trend is revealed in “Cohousing in Barcelona”, a book characterized by a love of details and discussion. Specifically, 2015 saw an important change in politics in Barcelona 2015, when "Barcelona en Comú" – a leftist alternative platform of social movements led by social activist Ada Colau, surprisingly came to power. Colao remained mayor until 2023. Already as an activist she had campaigned for more social housing in Barcelona and to strengthen civic cooperative construction efforts.

As early as 2014 there were already two initial pilot projects, for example, in which municipal real estate was leased long term to housing cooperatives: the conversion of an old rundown building from 1896 in the city center was handed over to a cooperative specifically for this purpose, which lovingly fitted out five apartments in it by 2018. The second project was the previously mentioned La Borda, which was much larger in scale; boasting 28 apartments in a new building it that even received the European Mies van der Rohe Award in 2022. In other words, there is already an interest throughout Europe in these new buildings in Barcelona that not only set high standards aesthetically but also in economic and social terms. Reading the book, it is easy to understand how this high quality comes about: it stems from the innovative framework conditions set by the municipal administration.

The two pilot projects were followed by the awarding of municipal plots of land to interested cooperatives each of which brings its own architects on board. For the construction of apartments to be used by the makers the city provides the cooperatives with land it owns or old buildings on a leasehold basis for 75 or 99 years. This means that the initial investment pays off for the developers thanks to the assured years of low-cost use they can look forward to. Currently, 150 families already live in such apartments. According to a memorandum of understanding between the city and the social housing developers a further 1,000 apartments are to be created in ten years, 600 of them as subsidized housing and 400 as cooperative apartments. The simultaneous increase in subsidized housing is intended to reach those people for whom even the comparatively inexpensive cooperative apartments are unaffordable.

No doubt about it, an ambitious goal. But why shouldn’t a city like Barcelona set itself goals? In the book the six cooperative projects completed to date are shown in as much detail as are the 12 which are currently in the planning stage – through photos or renderings, through plans and above all through interviews with those involved. Crucially, it is here and in the essays that architecture is ultimately not simply presented as a static object whose rooms and materials are up for discussion but as a constantly changing form which arises from a discourse with many participants – and which will continue to be shaped in the future.

In the highly diverse conversations with cooperative members topics that crop up include group organization, the tough discussion processes, the issues surrounding materials, the huge importance of shared spaces for achieving a practiced community – which can also extend “beyond the heteronormative core family”, the problems with financing or providing legal protection for the joint project.

What surely played a role here is that the four editors themselves live in one of the cooperative buildings. It meant they could ask the right questions, even though there are places where the book does not really develop the “critical view” of its topic which is promised in the introductory interview. Perhaps, ultimately, the participants lack the necessary detachment to achieve this. And in the introductory interview the four editors explain themselves that they decided on the interview format for the very reason that the entire Barcelona model is still “under construction”, is constantly moving and changing. As such, the book does not claim to provide a final evaluation but rather seeks to accompany a process that is still being shaped and which needs to be carefully monitored following the recent political changes.

So after reading both books the main thing that remains to be said is that the city of Barcelona has managed to bring about a change, which gives cause for hope, hope namely of making the stranglehold resulting from the financial crisis and mass tourism more bearable for the locals – not through one sweeping plan but step by step, house by house. This change is already visible in all its facets in the city’s latest small-scale and wonderfully diverse architecture. This is definitely good news for and from Barcelona.

Cohousing in Barcelona: Architecture from/for the Community

Publisher: David Lorente, Tomoko Sakamoto, Ricardo Devesa, Marta Bugés

Softcover, 220 pages

Separate English or Catalan edition,

Actar Books, June 2023

39 Euros

Barcelona. Urban Architecture and Community since 2010

Publishers: Sandra Hofmeister, Heide Wessely

Softcover

Separate English or German edition,

Detail Publishers, June 2023

59.90 Euros