Pop and urban space beneath heavy concrete

We meet the curators of the exhibition “Böhm 100: The Concrete Cathedral of Neviges”, Miriam Kremser and Oliver Elser, in the Church of St. Ignatius in Frankfurt’s Westend. It’s a gray winter’s day. Entering the church, we are shrouded by cool darkness. Passing the baptismal font, steps lead to the nave, which is only slighter brighter and where stained-glass windows bring a glitter to your eyes. The Frankfurt church is closely related to the Pilgrimage Church of Mary, Queen of Peace in Neviges, the focal point of the DAM exhibition. Both structures were designed by Gottfried Böhm in the 1960s, with St. Ignatius being consecrated in 1964 and Neviges in 1968. And there are also numerous architectural parallels. Which means that for the interview we are surrounded by Böhm’s architectural language.

Adeline Seidel: One hundred years of Gottfried Böhm and in the exhibition you focus exclusively on the pilgrimage church in Neviges. Why?

Miriam Kremser: Deutsches Architekturmuseum already staged an extensive Gottfried Böhm exhibition back in 2006. But naturally enough we also wanted to celebrate his 100th birthday. The pilgrimage church is most certainly one of Gottfried Böhm’s outstanding projects. And given that his pre-death estate is kept in our archive we are able to shed light on aspects of the structure that previously have not been addressed this way in an exhibition.

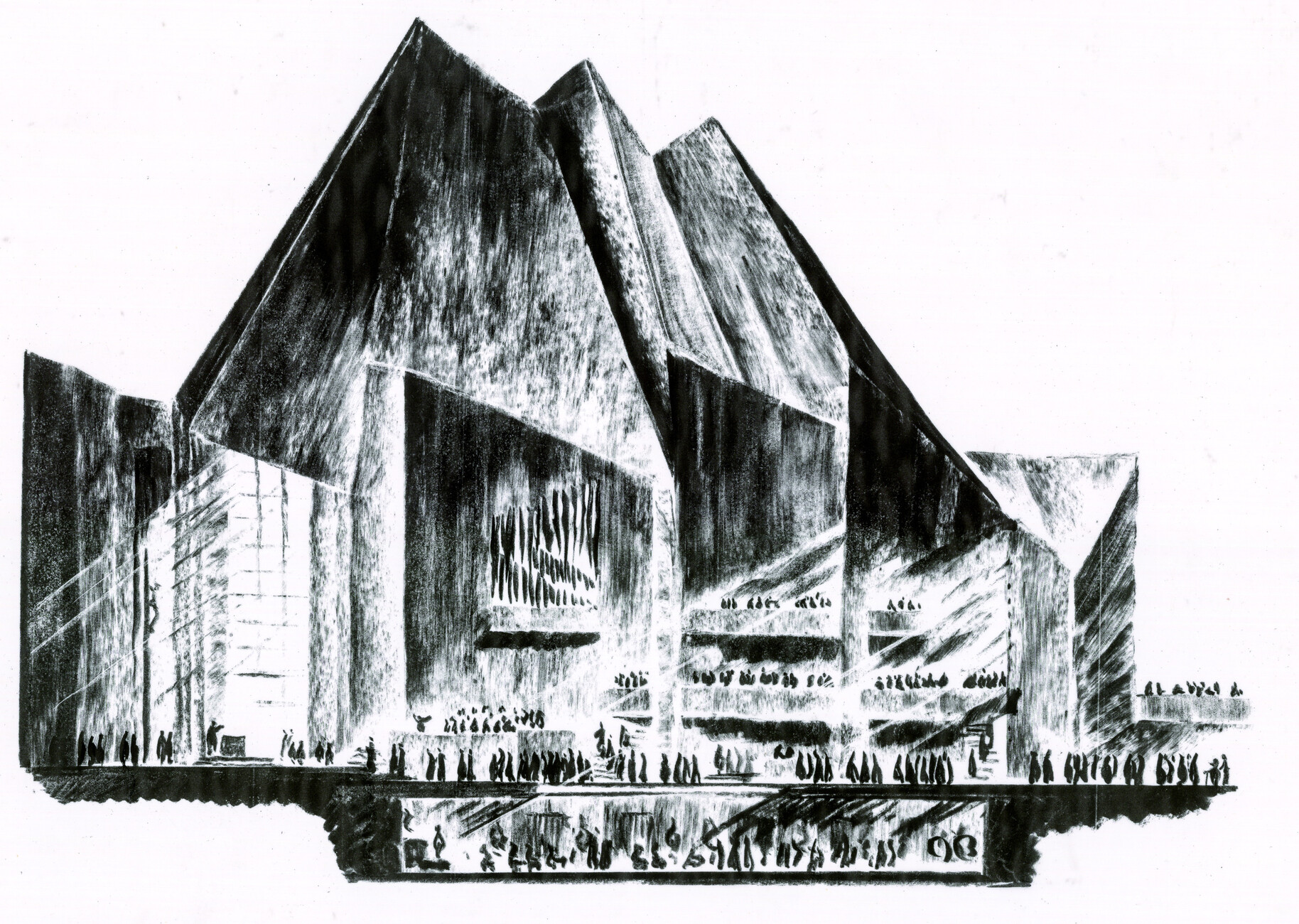

Oliver Elser: We are using a space in the building that Oswald Mathias Ungers designed for DAM that is not usually used for exhibitions, namely the auditorium. We are covering the almost six-meter-high walls of the lecture hall with black-and-white photo wallpaper, which make visitors feel as if they were in the church’s interior. Böhm meets Ungers! The graphic artists at Rahlwes.Pietz have developed a collage technique with which they superimpose historical photos such that you actually get an impression of the interior. We also reveal the various uses to which the church has been put. The nave could be altered at will, the furnishings could be moved –on the inside the character of the concrete cathedral was that of a public plaza.

Looking around here in St. Ignatius: Which elements are extremely “Böhm” and are also to be found in Neviges?

Miriam Kremser: The concrete roof with its folds is one element that is just as in evidence here as indeed it is in various other churches by Gottfried Böhm. But it has to be said: In terms of complexity none comes anywhere close to Neviges. You can also discover countless parallels in the design of the windows, but the colors differ enormously! St. Ignatius has much darker - violet and claret - tones. In Neviges the colors and their brightness can be described as nothing short of loud.

Well, it is the afternoon, it is January, and it’s raining – how is anything going to look bright today?

Miriam Kremser: Astonishingly, the windows in Neviges shine a bright red even when the light is not particularly good. The tones here in St. Ignatius give rise to more subdued light. In Neviges, Gottfried Böhm succeeded in doing something very special. He created a high, dark cave. Depending on the time of day the wall windows bathe the concrete in differently colored light. At times it is red, at others blue – depending on how it shines through the windows.

Oliver Elser: Both churches show a great sensitivity towards the use of the materials: The surfaces of the concrete were finished and combined in different ways, and there are counterpoints everywhere. Like here, the white marble altar – huge blocks, that are joined precisely but visibly.

As we mention surfaces, we keep on reverently running our hands over the different textures of the concrete walls and balustrades. We pass by the stained-glass windows, where Oliver Elser and Miriam Klemser point out another peculiarity:

Oliver Elser: Here – just like in Neviges – you can see names and even company logos on the windows.

Miriam Kremser: In Neviges you find, among other things, the names of family members hidden in the window motifs. As well as little drawings – like comics.

Oliver Elser: In St. Ignatius benefactors and construction companies were immortalized in the windows – the building contractor Philipp Holzmann for example. Talking of windows: Entering the exhibition in DAM, visitors are welcomed by a blue wall with green leaves that shine brightly in loud colors. This is certainly not the first thing you associate with Neviges, but Gottfried Böhm’s painting accompanies visitors along the pilgrim path. If you take a closer look the church is just as defined by 1960s Pop aesthetics as it is by the aesthetics of concrete so popular at that time. This is reflected in the colors, but there is also evidence of it in the furnishings: the light metal chairs with their plastic backrests could only have been made in the 1960s.

With Gottfried Böhm’s architecture one often thinks of his heavy, substantial religious buildings. In the 1980s, on the other hand, Böhm designed light, transparent structures made of steel and glass, such as the Maritim Hotel in Cologne and the Züblin headquarters in Stuttgart: In his long period of creativity is there one particular aspect that features in all his works throughout the decades?

Oliver Elser: Gottfried Böhm headed the Department of Urban Planning at RWTH Aachen University. Topics such as living together as a community and creating neighborhoods were important even back then. That is also evident in his designs, for example for Prager Platz in Berlin, which actually looks markedly postmodern. In his diagrams however he brings it to life with a circus, showmen and jugglers. Böhm had a longing for public spaces that are not just passageways but in which there is life. Edifices such as the Maritim and the Züblin HQ have incredible interiors that intended to ensure that the people in a building form a sort of community.

Gottfried Böhm the urban developer? Where is there evidence of that in Neviges?

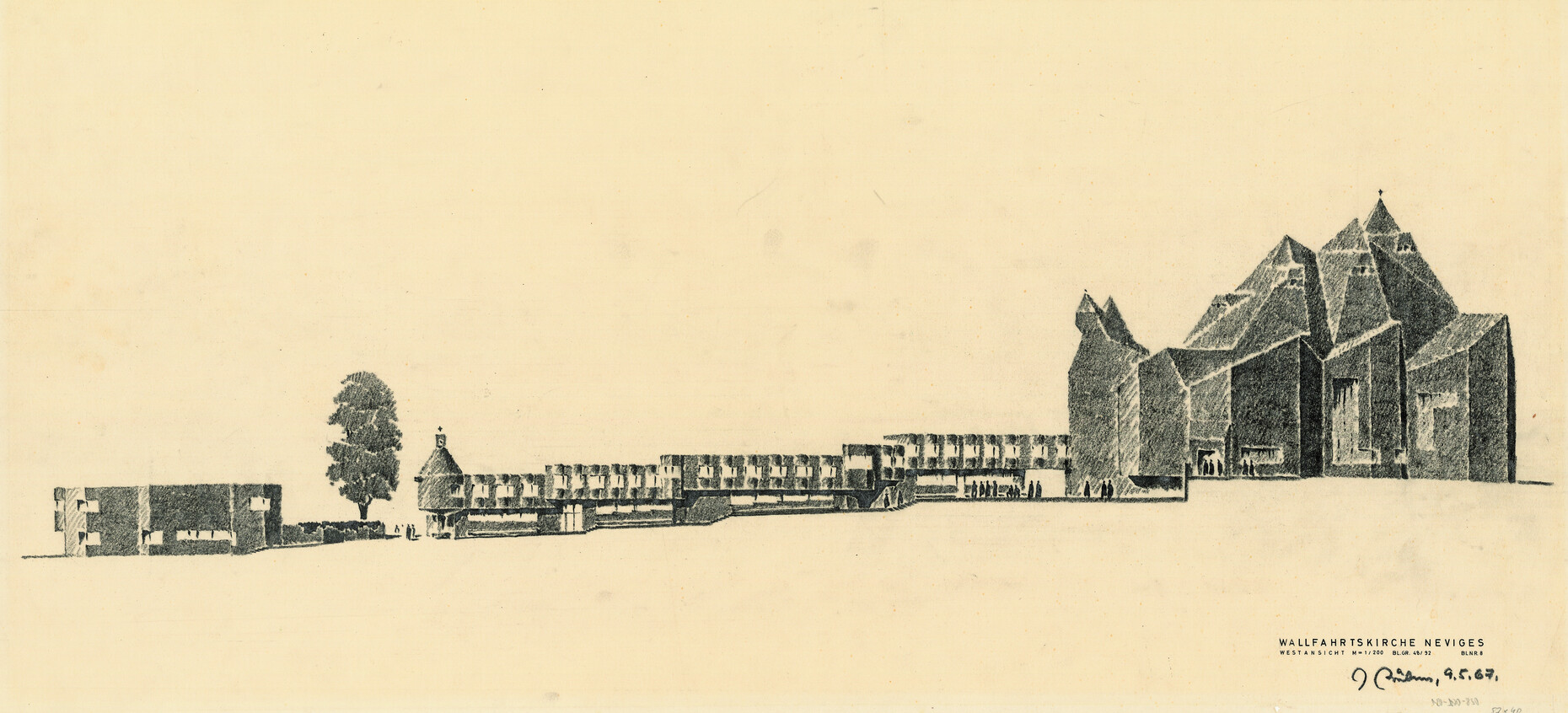

Oliver Elser: At the time Gottfried Böhm won the competition because he was the only person to have any idea about urban space! Everyone else was just designing sculptures. The most absurd sculptures: giant coffee machines, funnels, hearts, nuclear reactors, and cooling towers. The Catholic Church wanted the pilgrimage church to have a clear “expression”. That was a directive from on high. And those taking parting in the competition tried to find this expression in borrowed designs. Böhm was the only one not to resort to a readymade shape, proposing instead a sort of tent with a large space for the community.

Miriam Kremser: And instead of just putting a copy-and-paste shape on the building site, he also considered the surroundings, integrating them in the overall design. He orchestrated the pilgrimage church in Neviges, for example, as the end of an ascending pilgrim trail, thereby creating a link from the road to the sacred space. Gottfried Böhm used the terrain here to determine the specific position of the church – he interwove the surroundings with the pilgrim trail, with the small curve, before one reaches the church.

Oliver Elser: And it is this interest in urban space that pervades his entire oeuvre.

Böhm 100: Der Beton-Dom von Neviges

DAM Deutsches Architekturmusuem

Schaumainkai 43

60594 Frankfurt am Main

18th January till 26th April 2020