The New Class

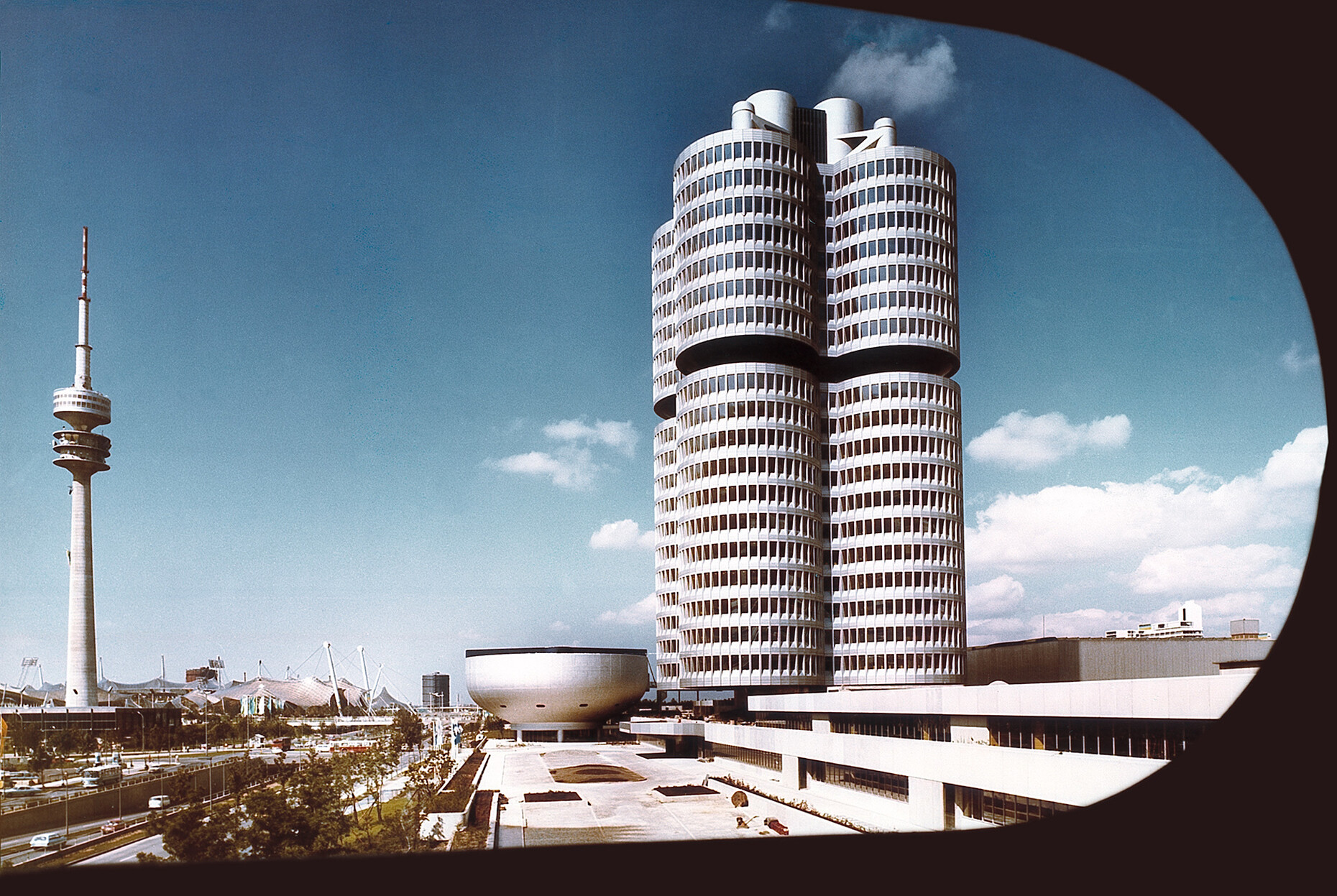

A modern office building boasting space that could be divided up flexibly, a building with an awesome façade, but one that would also fit in well with the surrounding buildings – this was the brief when BMW launched an architectural competition in 1968. In response, Vienna-based architect Karl Schwanzer submitted a design for a building that was a feat of engineering – a futurist suspended construction almost 100 meters in height and with four main cylindrical elements which given the unique construction looked firmly set to become a landmark building for the automaker. “For Schwanzer, the BMW HQ job came at the right moment in his architectural career. He had already designed and realized several such buildings and headed Vienna Technical University’s Dept. of Building Theory and Design since 1960,” reports Leonie Manhardt, an employee of his for many years. The tender text stipulated that there be clear architectural links between the new office block, a data processing center, and a multistory car park. And the buildings were also expected to form a harmonious whole with the off-site administrative buildings. Moreover, there was a need for a carpark because until then BMW employees had used the grounds to park their cars.

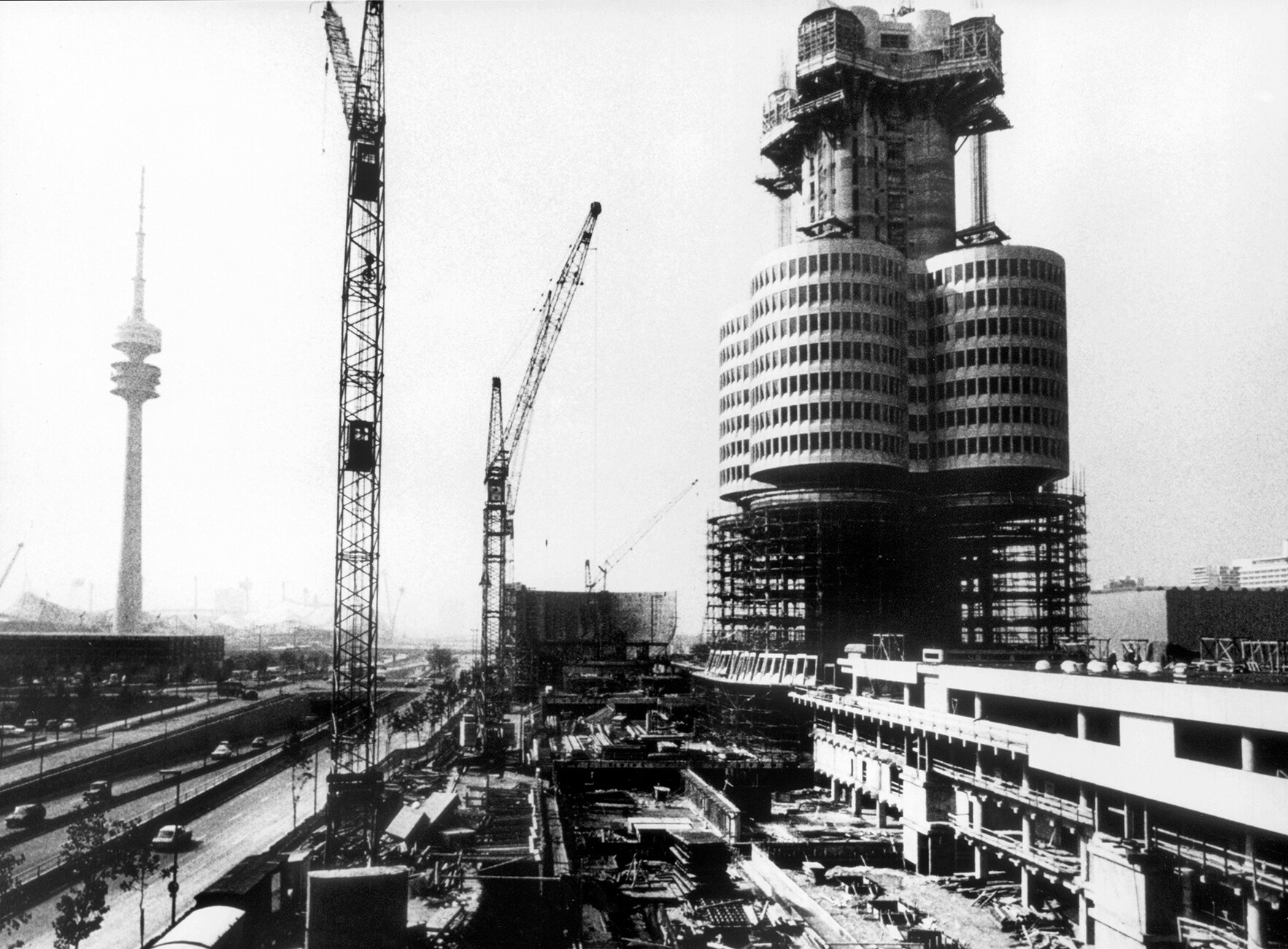

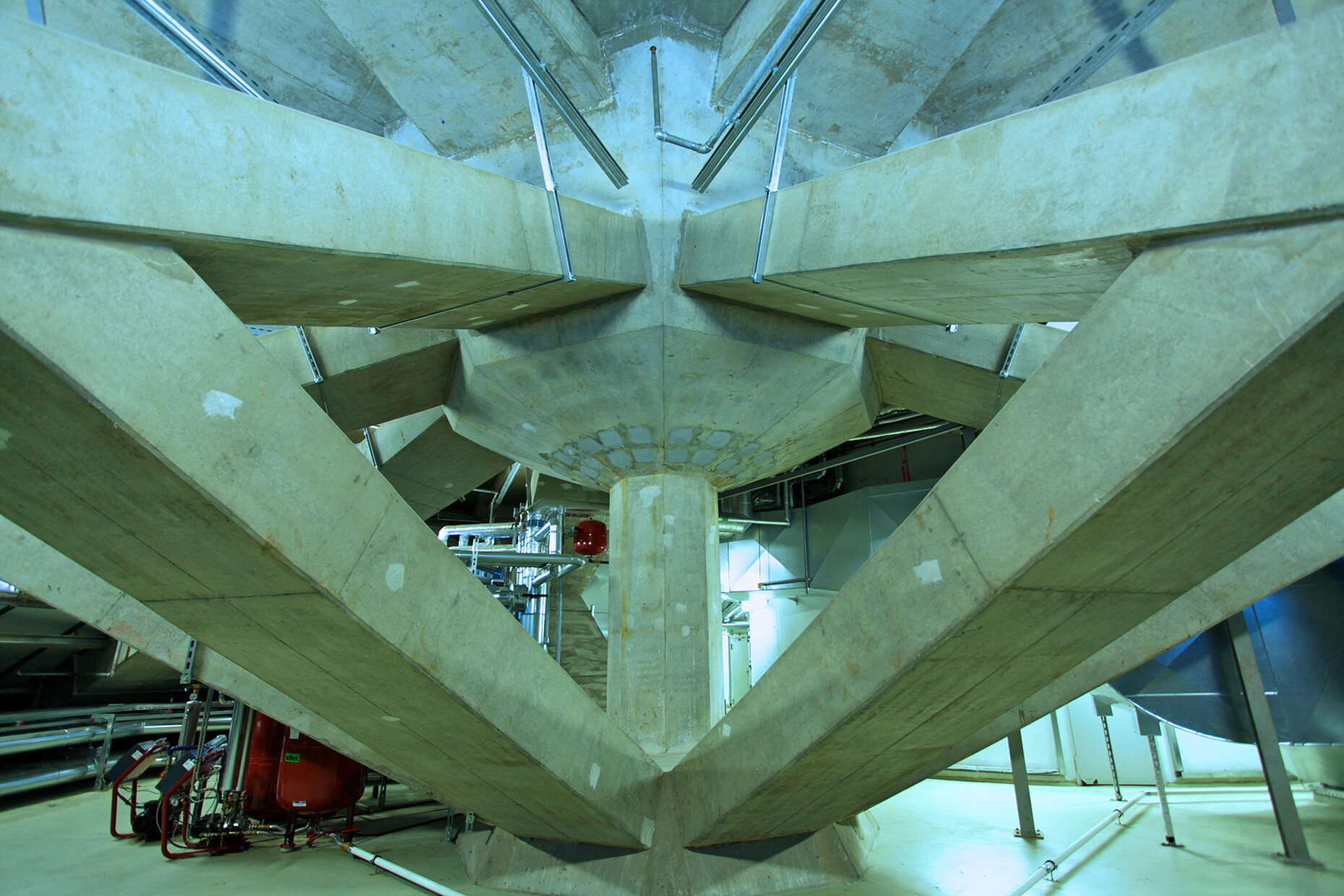

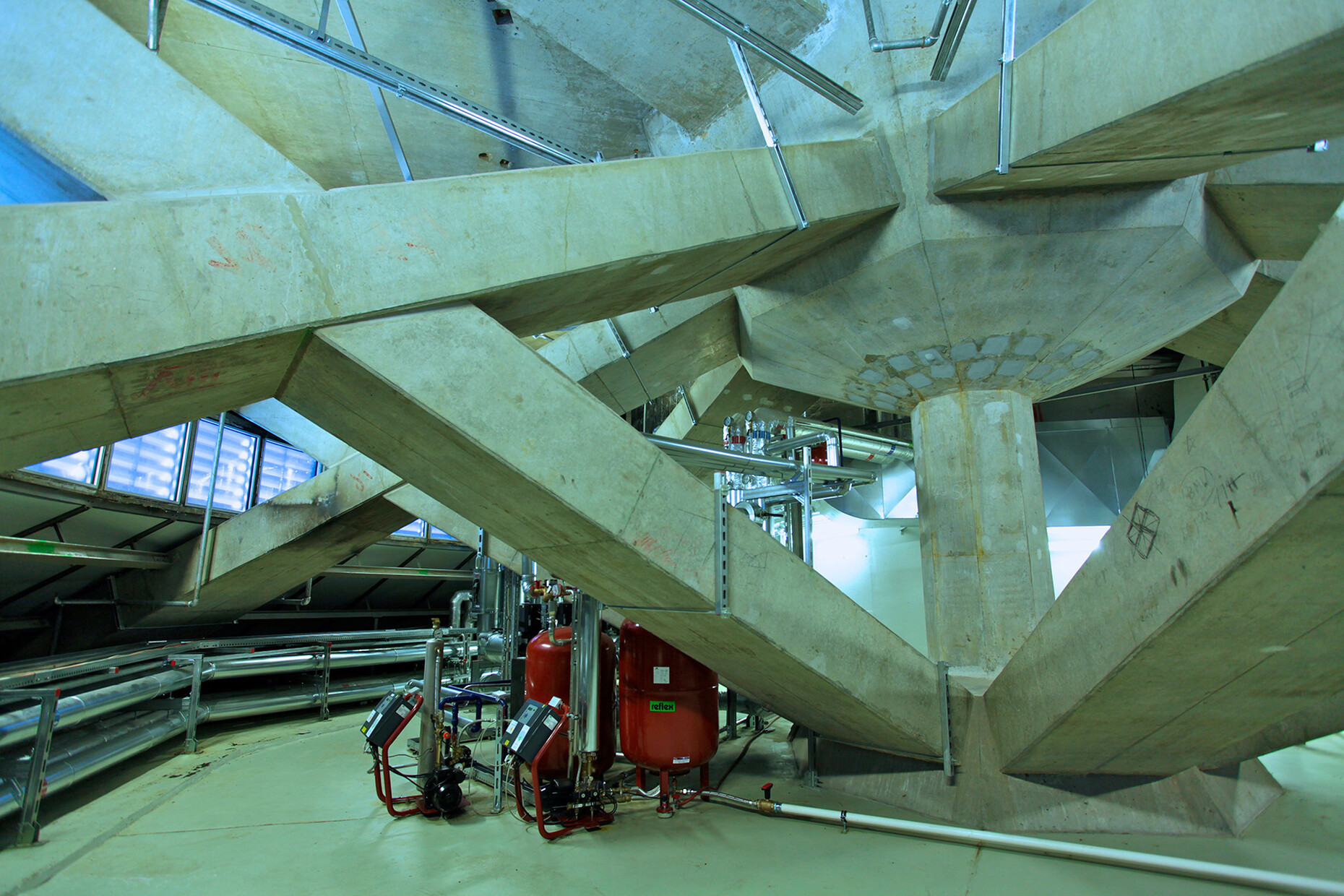

Schwanzer’s experimental design with its round offices and space that could be used flexibly polarized opinions. At the end of the day it was BMW Sales Director Paul Hahnemann who won over the company’s management. He had an accurate working model produced showing exactly how one of the cloverleaf-shaped stories functioned. He thus allowed people to get a good idea of the design with his model which was realized at the Bavaria Film Studios. Given that the plans for the BMW high-rise were so progressive, Schwanzer’s brainchild set new standards in modern office architecture. At a height of 99.5 meters and with 22 stories, to this day the high-rise represents the ensemble’s crowning glory. In point of fact, these cylindrical towers were suspended from a cruciform steel structure. To this end, the upper stories were the first to be produced; further elements were manufactured in parallel at ground level. The building could was thus erected in several segments, with each new set moved slowly upwards along the reinforced concrete core hydraulically and in small stages. “The project was characterized by an extremely tight building schedule as the complex’s exterior needed to be completed in time for the Olympic Games in August 1972. It was with this in mind that the decision was taken in favor of a suspended concrete structure that allowed for slender supports and the simultaneous realization of the building shell and the interior,” Manhardt remembers.

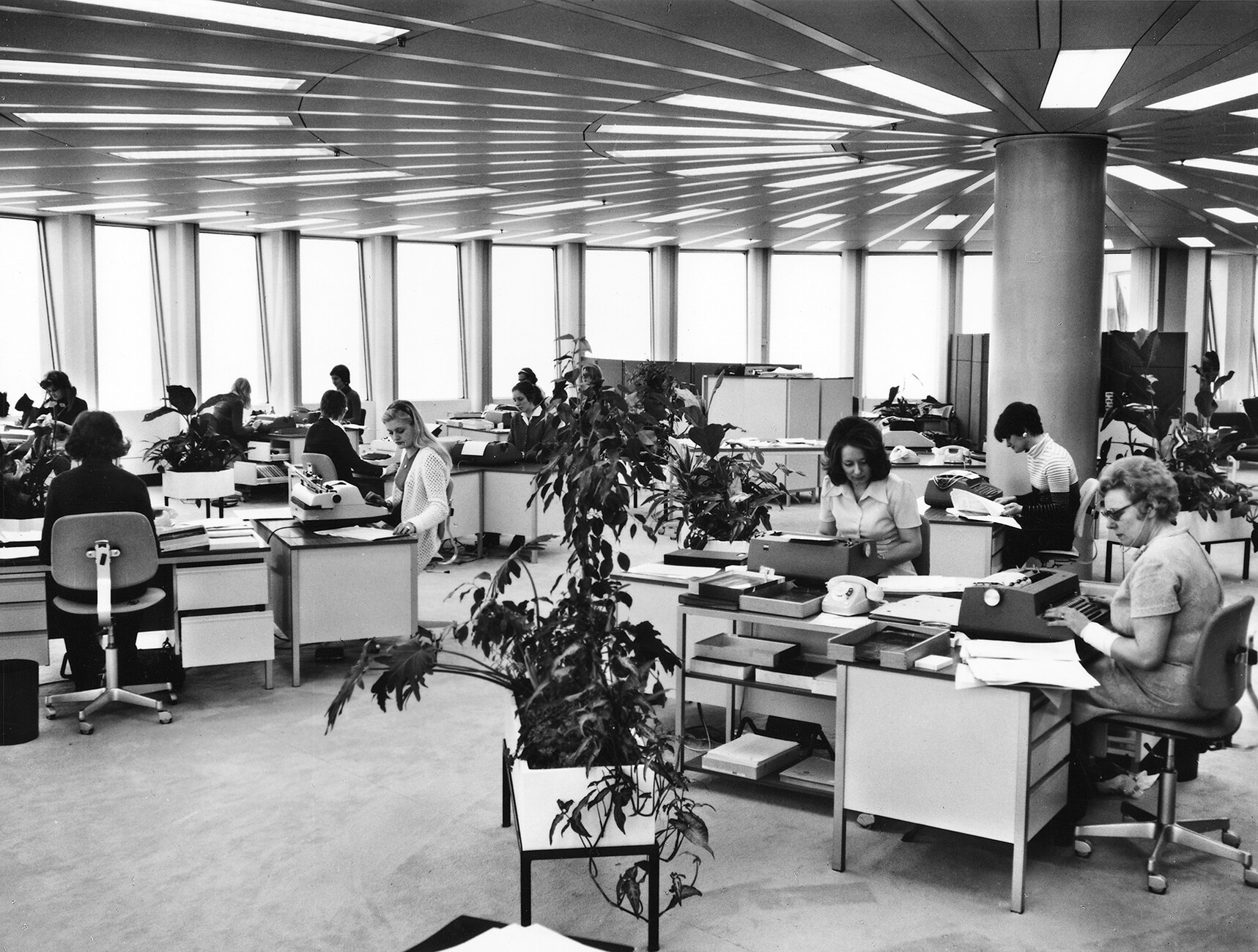

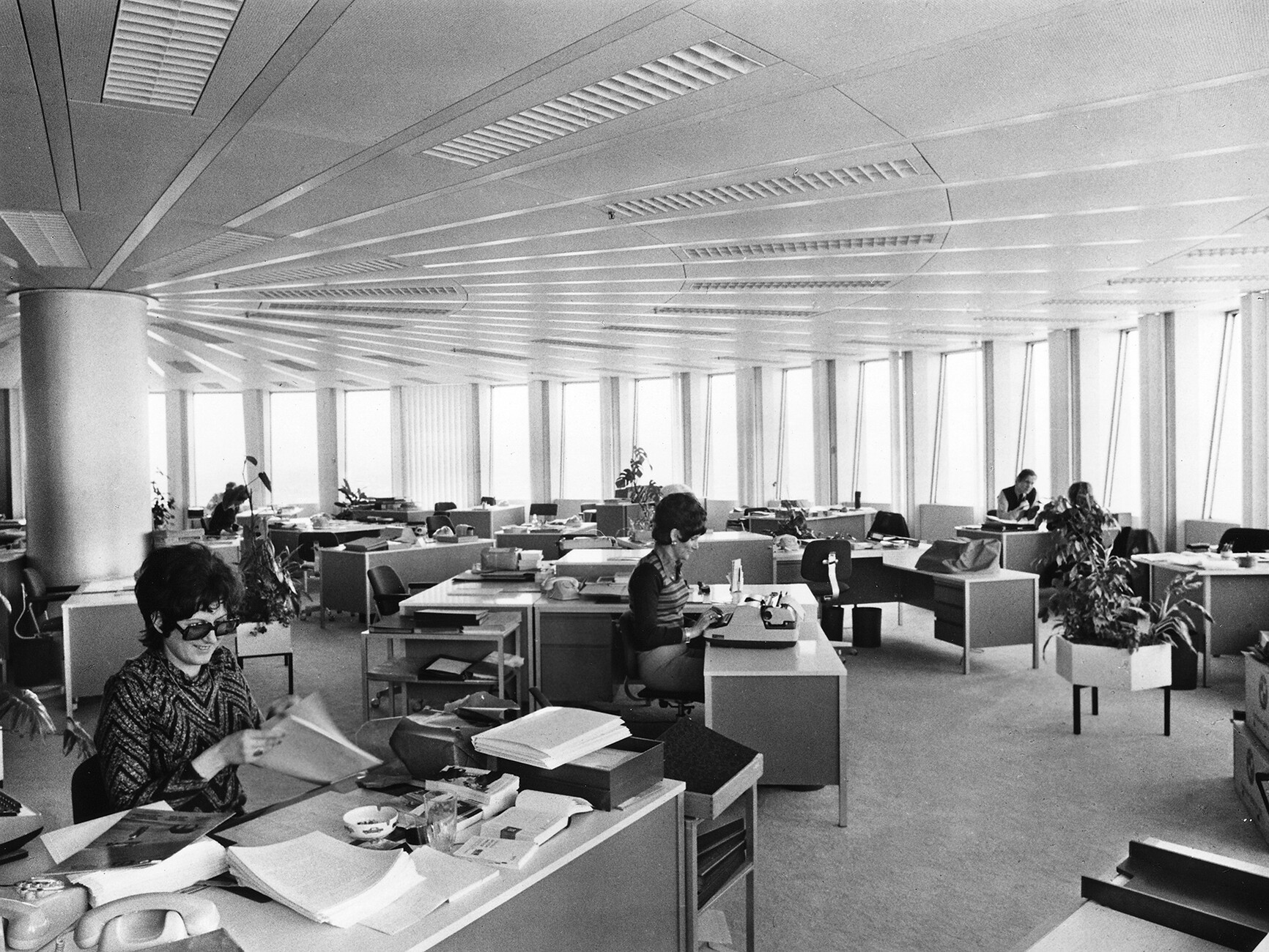

With Schwanzer’s innovative concept for the Four-Cylinder’s façade and its interior, the architect was pursuing the concept of “constructed communication”, aimed at achieving a symbolic end product and at promoting productive work processes. To this end, two corridors lead crosswise across the core of the individual stories, connecting the various team offices with one another. Almost all employees share the same space and executive offices are a rarity. “As of the 1950s, administrative buildings had clearly moved away from cubicles to open-plan offices or a combination of the two. It was foreseeable that the advance of cybernetic organizational principle would only further this development. Experience had shown that long horizontal paths were something to be avoided and that vertical mechanical communication channels were more efficient in both operational and business terms. Large and coherent office spaces allowed for a kind of office organization where distances were short and offices not only easily altered but also clearly arranged. In other words, the resulting office world was organically structured, with a central contact area allowing for in-depth discussion in the area around the central core, where the elevators are located,” summarizes Manhardt. BMW put things in a nutshell when it unofficially dubbed it “Ein Bürohaus der Neuen Klasse” (a new class of office building), when describing the standards set by the building. Admittedly, when it became necessary to refurbish it in 2004 the company carrying out the work, Peter P. Schweger, needed to clean and reinsulate the façade as well as to replace a large number of its windowpanes, but fortunately the structure’s dynamic feel remained unchanged. Today, both the impressive company headquarters and the BMW museum, also designed by Karl Schwanzer, are heritage-listed and are considered one of Munich’s landmarks. This year marked the 50th anniversary of this iconic building and BMW is celebrating the fact with a special ceremony in July.

Multifunctional approach

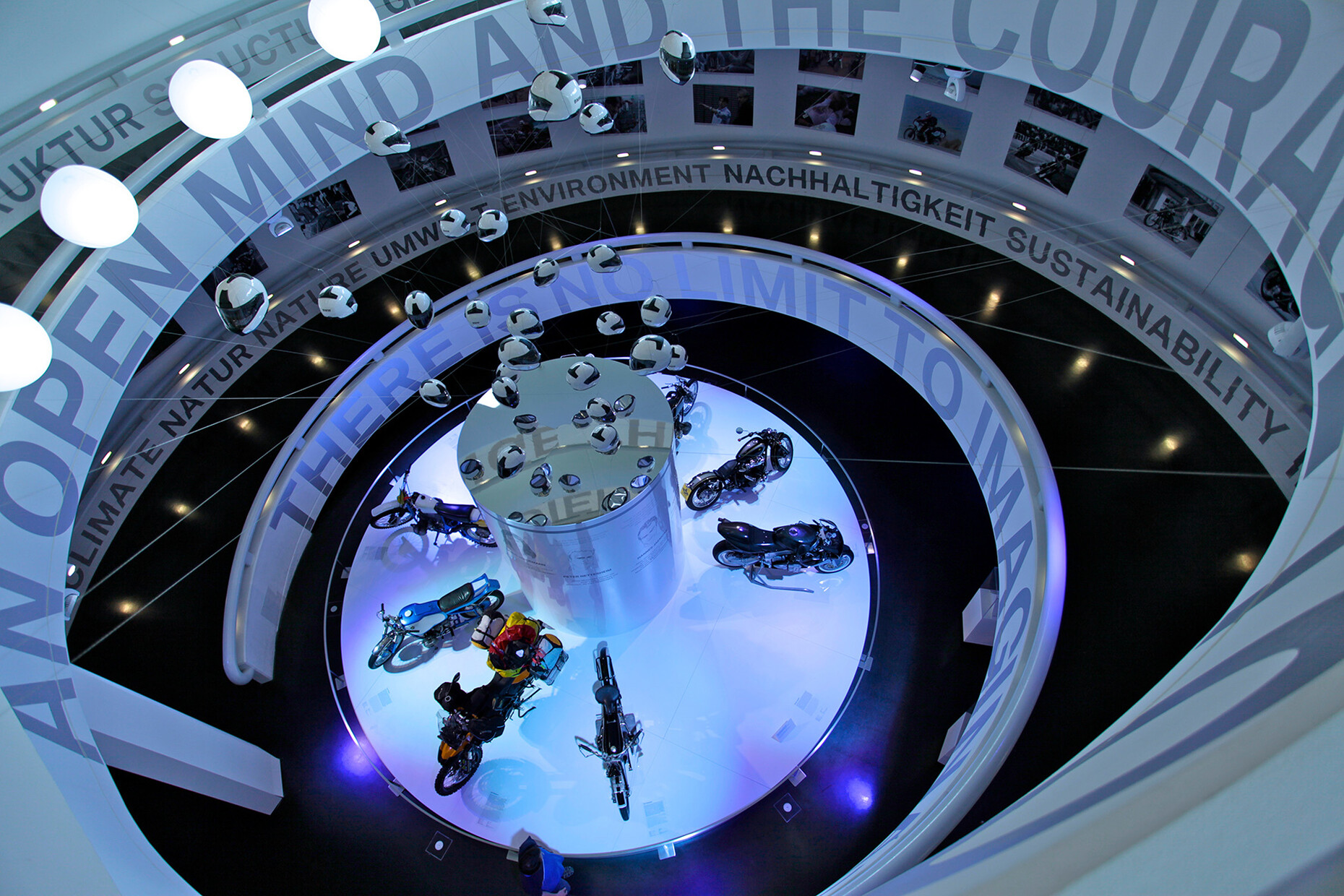

Since the end of the 1960s, the site itself has also become considerably more built-up. Indeed, with Austrian architect Wolf dPrix of Coop Himmelblau adding a brand experience and delivery center to the “Four-Cylinder” in the form of “BMW-Welt”. “At the start of the competition the specifications for the building had not been decided, apart from the fact that it was to be multifunctional. Then I started thinking about a roof that would function not as a space-determining element but as one that distinguished the space. As the project evolved, it was possible to put in place all the desired functions. This is a hybrid entity, a cross between an urban arcade, market square, and the stage in a playhouse. What we have created is more than just a showroom,” is how dPrix puts it. Coop Himmelblau’s architecture harmoniously complements the existing BMW icons. “What has come into being is an urban ensemble with a double cone serving as its visual turning point at the adjacent crossing. In addition to its proximity to the ‘Four-Cylinder’, the building’s multifunctionality was a decisive criterion,” explains dPrix.

Plans for further developing the site are also already afoot. The design by architecture practices OMA Rotterdam and 3XN Copenhagen recently won the “BMW Munich – urban manufacturing” international architecture competition. BMW is now looking at further holistic development projects taking account of the district around the plant. “The first two major projects will be the new buildings for vehicle assembly and body construction. With them we will be laying the foundations for innovative, sustainable and competitive production processes. We are gearing our factory up to produce the models of the ‘new class’, our first step into the third phase of electromobility. The architecture competition marks our aim to open the factory outwards and embrace downtown Munich. The thinking behind this transformation of our plant is that it is a means of safeguarding the future of the location and the jobs there,” reports factory manager Peter Weber. in other words, a new chapter has now started in Karl Schwanzer’s vision of "building to shape tomorrow”.