From Big Bang to BIG

A warm Friday in June 2019: Two clearly distinguishable groups of mostly young people are crowded together on a Copenhagen city bus. One group is clad in T-shirts commemorating metal bands and sports martial-looking tattoos, while the other has brought skis and snowboards along. Both groups are on their way to two major crowd-pullers in town, located but a stone’s throw from each other: the rock music festival “Copenhell” and the new ski slope “Copenhill.” While the festival has been bringing music fans to Copenhagen’s city borders since 2010, the artificial ski slope is a brand new attraction. It belongs to a new power station that was built according to designs by BIG Architekten and that turns Copenhagen’s refuse into electricity and district heat. The building with its two functions is typical of the architecture created by Bjarke Ingels and his team. For his project “Bjerget” (Mountain Dwellings), completed in 2008 in Ørestad, a few kilometers from the “Copenhill” site, Ingels had already stacked an apartment complex onto a parking garage: This was to be his breakthrough as an architect.

The new power station is a landmark that can be seen from many places in the city, despite being located several kilometers outside of the city center. Just as well then that it is compelling to look at. As it stands, it allows skiers of different abilities to wedel down the plastic foil-clad piste at well over 20 degrees ambient temperature, accompanied by the bass tones drifting over from the “Copenhell” festival.

Heaven and hell lay closely together in other ways too as the power station took shape. Originally, the design was to include another sensation alongside the ski slope. Instead of a permanent trail of smoke, its chimney was to emit smoke rings from time to time – whenever the power station had emitted another ton of CO2. The idea was to be implemented by a team headed by inventor Peter Madsen, Denmark’s own Gyro Gearloose so to speak, who among other things was working on a rocket project. In 2017 Madsen achieved unhappy notoriety when he murdered the journalist Kim Wall in a submarine he had built himself. The smoke ring project is currently on hold for financial reasons – and so the 120-meter-high chimney today emits clouds of rather conventional-looking smoke instead. According to BIG, however, there is an intention to retrofit it if sufficient funds become available at some point.

The new waste-to-energy plant is however not entirely uncontroversial. Opponents have called it too large for local requirements. The accusation has been leveled not least at the architects for supporting this in order to have enough space for their ski slope. Local politicians on the other hand are said to have wanted to create a clearly visible landmark as a crowd-puller. The thought is not entirely far-fetched in an era in which star architects are often consulted for flagship projects. BIG now has around 550 staff and has long since found its place in the league of the likes of Zaha Hadid, Norman Foster or Herzog & de Meuron, the “usual suspects” for tasks such as this.

With its new exhibition “Formgiving” at Dansk Arkitektur Center DAC too, the architecture studio has taken on one such prestige job. Last year the architecture museum moved into the new multi-purpose building BLOX in central Copenhagen – built after a design by Bjarke Ingels’ former employer OMA. For the second year in the new location the institution was planning its first blockbuster show. It was only natural to ask BIG to step up for the job, after all, smart Ingels is not just without question Denmark’s most famous and sought-after architect de jour, but true to his name he also has the self-confidence to think big. Which in this case means: on a world-historical scale.

Visitors walking up the stairs leading to the exhibition space are accompanied by a timeline spanning from the Big Bang to the present day. With this, BIG and Ingels want to point to change as the eternal constant. But we might also arrive at a different reading, namely that the result and current preliminary apex of evolution is BIG’s architecture. Ingels does indeed present his buildings with impressive graphic diagrams, showing us that each design is objectively the best of all possible solutions. His meteoric ascent – Ingels is still only 44 years old – is based on precisely this power of persuasion. His unconventional way of thinking, combining functions and enhancing his buildings with unusual experiences for their users have without doubt made him the figure with the biggest impact on our modern-day architecture. But by the same token he has also turned the communication strategies of his craft upside down, for example, with his comic book “Yes is More,” in which he explains his design principles in speech bubbles. Ingels is omnipresent in the media – in the cinema, on Netflix, in countless articles and of course in his exhibition, where we encounter him life size on not one, but two monitors.

In contrast to the last monograph “From Hot to Cold,” which took place only three years ago, the further expansion of the firm cannot be overlooked. And the focus of the presentation has shifted, too. The previous show endeavored to provide proof of the BIG architects’ principles by reference to each project presented individually. The thrust was: We find a solution beyond what has been considered thus far for any place of your choosing in the world, from Middle Eastern desert to Arctic Circle – and our solutions optimally take all requirements into account while further creating surprising value added. “Formgiving” relies much more heavily on visually overpowering its audience. The high-ceilinged exhibition space with its countless models and image panels suspended from the ceiling – hung one in front of the other, three to four panels deep – appears kaleidoscopic. The flood of information seems to be saying: BIG is so successful it is almost impossible to imagine. Presenting each project individually? Inconceivable, there are just too many! Instead, all designs are grouped into ten overarching topics: “Pool,” “Show,” “Lift,” “Host,” “Respond,” “Adapt,” “Merry,” “Grow,” “Bond,” and “Productize.” They are color coded and are each assigned an area in the exhibition hall which is marked out in the respective color on the floor.

The heading “Merry,” for example, involves the idea of combining different functions. Here we see an impressive model of the gigantic flood-protection system that the architects are currently building around Upper Manhattan and that will at the same time be a new park with numerous leisure offerings. The gallery building “The Twist,” currently under construction near Oslo, also belongs to this section. It doubles as a bridge across the river Randselva and so links two parts of a sculpture park. And of course, “Copenhill” also falls into this category.

“Lift” is concerned with buildings in which a special focus is placed on vertical dimensions – first and foremost the various high-rise projects BIG is currently working on. One example is the Two World Trade Center at Ground Zero, 400 meters in height, which was to house the media groups 20th Century Fox and News Corporation. The design includes open areas in lofty heights created through protruding or receding architectural elements, in a similar fashion to that of the design for the Omniturm tower currently being completed in Frankfurt. However, the future of the Two World Trade Center project has been cast into doubt, with the two media giants having withdrawn as tenants. The residential complex “AARhus” on the other hand has just been inaugurated, and is made up of two arrow-shaped apartment buildings in the direct vicinity of the lido also created according to a design by BIG. For “AARhus,” the studio has further developed its typology of high-rises. The new construction thus belongs to the same family as lower-rise buildings such as 79 & Park in Stockholm and the “Courtscraper” VIA 57 West in Manhattan. The architects conceived an alternative for the Sluishuis on the edge of Amsterdam. For the building, likewise located on the waterfront, BIG juxtaposed its characteristic roof line, drawn down on one block corner, with a “pulled-up” corner, thus creating an enormous gate to the courtyard. Boats may enter through this gate and anchor in the small marina in the courtyard. In the exhibition the architects assigned this project to the topic area “Host,” alongside the recently completed MÉCA in Bordeaux, a cultural center on the river Garonne. The characteristic feature of that project is a huge passageway in its middle, which may also be used as a sheltered stage and exhibition space.

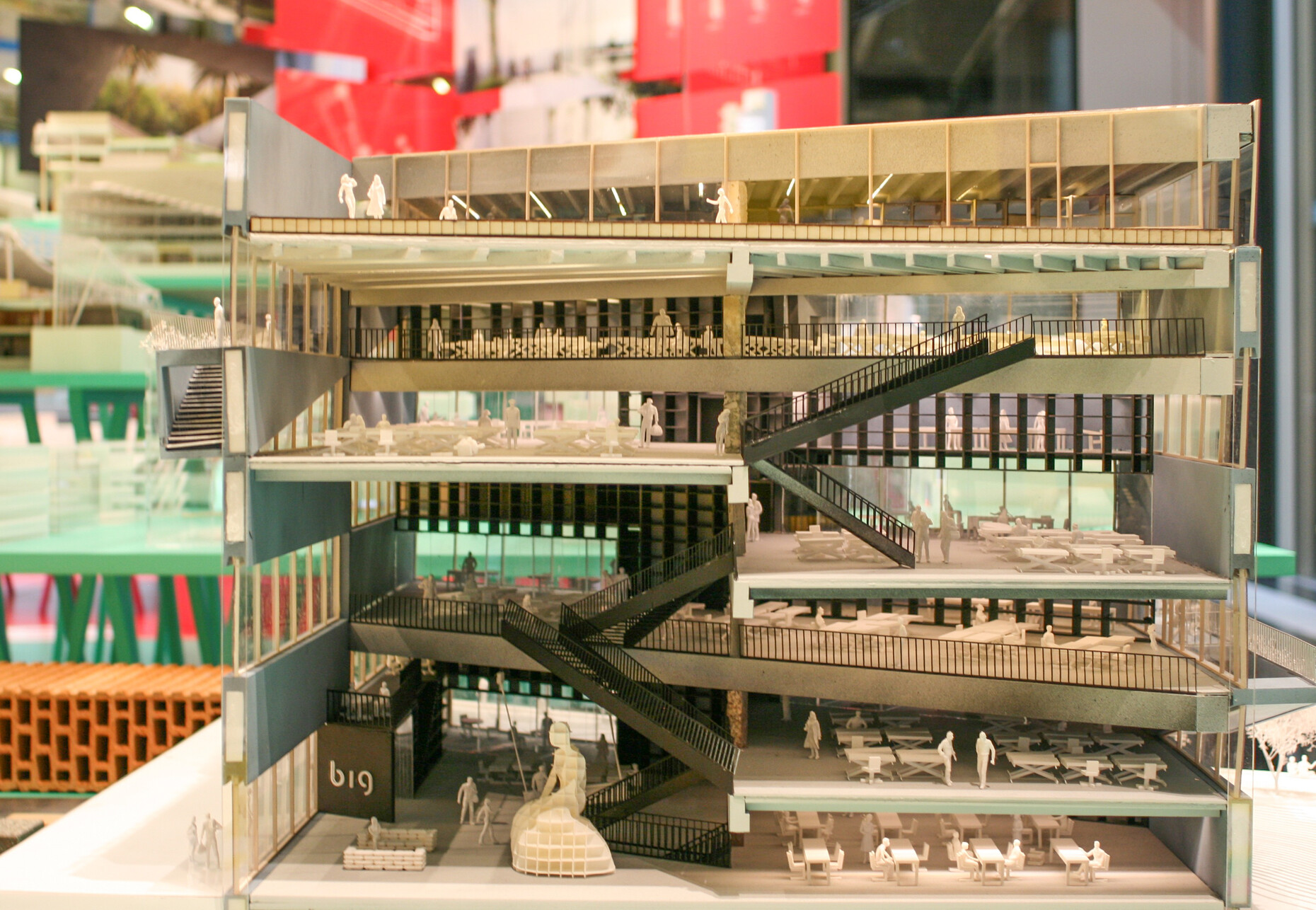

What is perhaps the most exciting topic area in the exhibition can be found under the heading “Pool” – a chapter that isn’t, as you might think, concerned with bathing, but in fact with the pooling of ideas and creative forces. Here BIG presents its various office projects for Google, as well as a first glimpse at the new BIG headquarters currently in planning. For themselves, Ingels and his team have devised an interior made up of overlapping mezzanine floors, intended to allow for a great number of visual axes. In relation to the complex spatial experience set to be created here, the architects point to the famous architectural inventions of Piranesi as a role model – a historical reference that is unusual for BIG and a rare indication of the fact that of course not even Bjarke Ingels’ architecture is developed purely from its function.

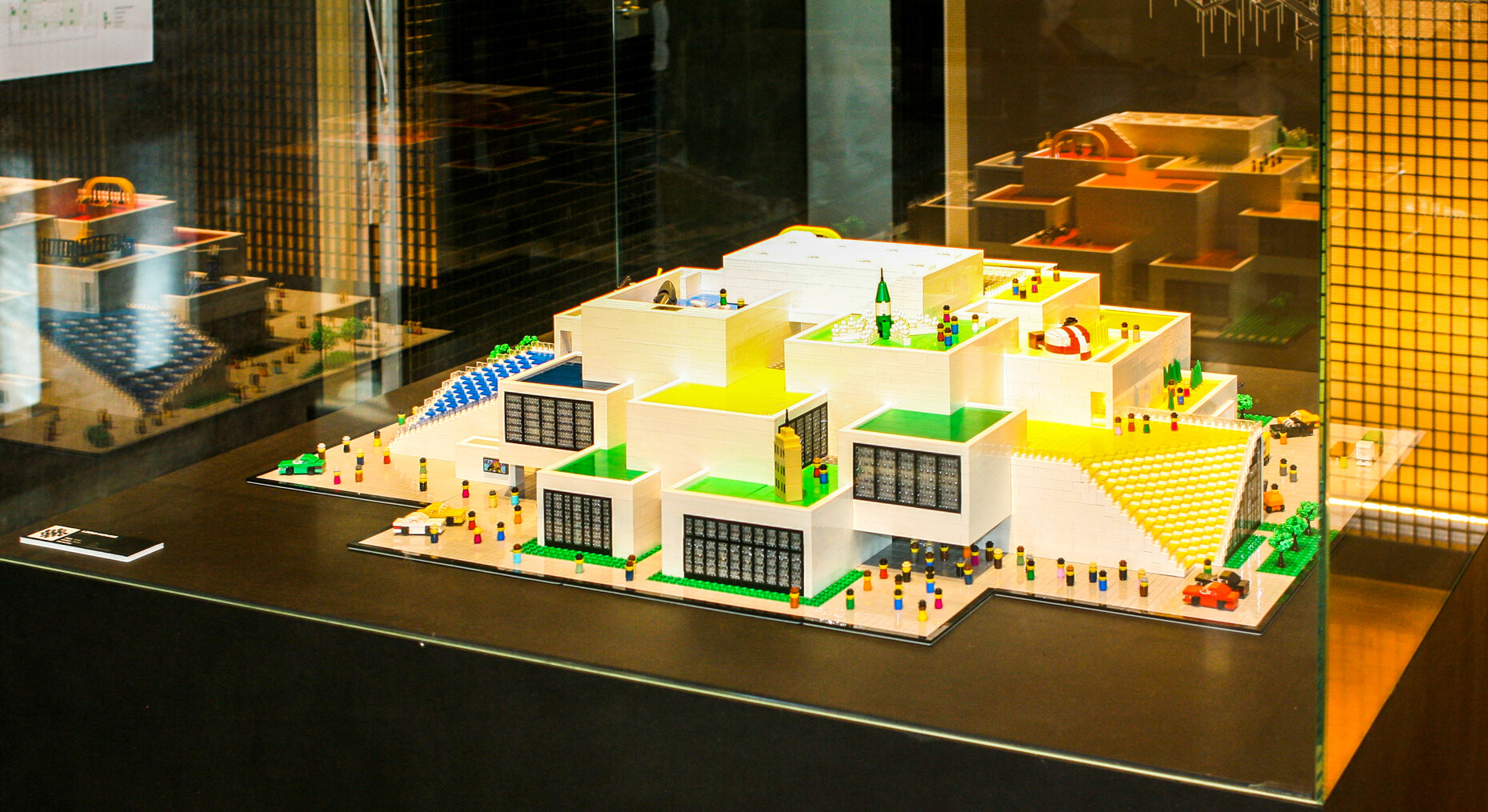

It goes without saying that aesthetic convictions play a crucial role in his formal language. Depending on your point of view it might appear honorable or somewhat insincere not to emphasize this aspect a great deal. However, viewers will find it hard not to acknowledge that BIG’s force of innovation remains remarkable, despite the sheer number of projects the office is planning or implementing at the moment. The existing typologies are being further developed and are still able to surprise us with truly new solutions at regular intervals. If anything, a danger of stagnation seems to stem only from the constant repetition of the “pixel aesthetic” of misaligned cubes stacked up to form pyramidal, arched and curved figures. We encountered this aesthetic in Ingels’ 2016 Serpentine Pavilion in London, in various high-rise designs, of course in Billund’s Lego House and now also as a shoe rack for Parisian department store Galeries Lafayette. There’s a danger here of BIG lapsing into formalism, especially because the demand for signature architecture is great and clients want their own typical Bjarke-Ingels building.

Ingels certainly doesn’t seem to be sharing these concerns. His gaze is set far on the future, in which he believes new technologies will inevitably lead to new architecture. And so BIG has already begun planning an extraterrestrial settlement, the model of which concludes the tour of “Formgiving:” from the Big Bang to the stars. Some time is sure to pass before Ingels is able to build on other planets. Maybe he’ll go skiing in Copenhagen in the meantime.

Formgiving

Dansk Arkitektur Center

Bryghuspladsen 10

1473 Copenhagen

Through January 5, 2020

Opening hours:

Daily 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Thursdays 10 a.m. to 9 p.m.