The misunderstood utopian

Andrea Eschbach: Mr Joanelly, how did it come about that you teamed up with Monika Annen to curate an exhibition on the work of Elemér Zalotay?

Tibor Joanelly: I first met Elemér Zalotay some five years ago while doing some research. I called him and traveled to Ziegelried near Schüpfen, a charming rural hamlet in the canton of Bern. And what I saw standing there on the fringes of a conservative residential area of detached houses radically overturned the one or other assumption. And from that the idea evolved of an exhibition that would present his work in Germany, Austria and Switzerland for the first time.

Why?

Tibor Joanelly: Architect Martin Klopfenstein put it in a nutshell in his obituary: Zalotay’s house reads like a cross section of everything that is conceivable and feasible: Essentially rationally organized and over the years overlaid with a layer of objets trouvés it rolls primeval hut, Modernism and romanticism all into one. It is impossible to detect where planning ends and improvisation begins.

Zalotay’s house is reminiscent of a kind of brut gesamtkunstwerk.

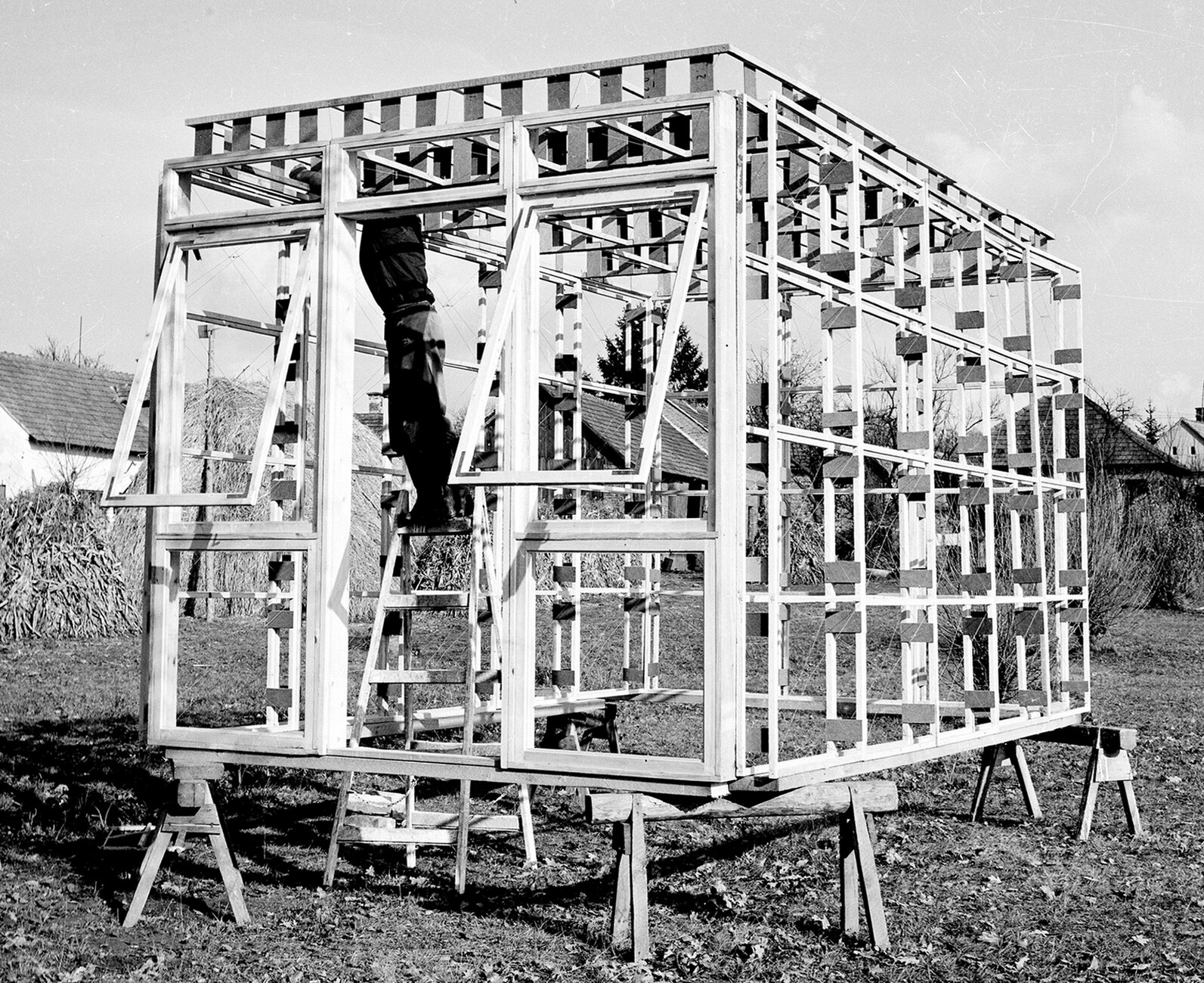

Tibor Joanelly: Yes, he worked on his house for 40 years, a sloping glass facade, steel cables, chains, wooden components, sheet copper, stones and recycling material were combined to create a marvelous potpourri.

But there is much more to it than that as you found out.

Tibor Joanelly: Yes, underneath this rampant decorative layer there is a regular, lightweight structure that speaks volumes of its creator’s inventiveness. Zalotay developed a structural system for it that he then had patented. Steel cables were drawn over a wooden frame to produce a sturdy base. Zalotay considered his construction to be an experimental house, it was the nucleus of a town for him.

What was his intention in realizing such an experimental house?

Tibor Joanelly: Its roots can be traced back to the 1960s in Hungary. In 1961, straight after graduation he planned a three-kilometer long “linear house” for a suburb of Budapest. The block was 30 stories high and intended to accommodate 70,000 people. A unique city housed in a single structure complete with a theater, cinema, nursery, school and restaurants. And each of the 20,000 units was to offer the same view of green countryside. A democratic concept.

What was Zalotay’s goal?

Tibor Joanelly: He saw building as a social undertaking: Suitable accommodation should be affordable for everyone. After the Hungarian Uprising in 1956 there was a severe housing shortage in Hungary. He wanted to solve the problem in one fell swoop.

And in the process he anticipated in a radical and farsighted manner some things that are in current use today.

Tibor Joanelly: Absolutely. He conceived of prefabricated apartments featuring lightweight structures that would be delivered intact to the building site. Moreover, he also had the idea of a vertical curtain of plants in front of the windows – a vertical forest such as the one Stefano Boeri would realize in Milan over 50 years later.

What was the reception of his project like?

Tibor Joanelly: It caused a huge sensation; a British architecture magazine entitled an article on Zalotay’s evolving habitat “Corb plus” – arguing it was the logical extension of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation. His idea was the subject of a controversial debate In Hungary. But then Zalotay fell out of favor with the functionaries. By emigrating he hoped he would be able to realize his vision elsewhere.

Did he succeed?

Tibor Joanelly: No. His ideas proved too radical to actually be implemented. With the exception of his own home, his designs in Switzerland remained ideas on paper. Up until his death he focused almost obsessively on issues of affordable housing. For example, he also developed a non-elitist do-it-yourself approach. Within the skeleton of a high-rise that he called a “megastructure” the inhabitants were to install their own houses. Similar to furnishing a house with items from Ikea, based on the patented system of his own house.

A man with big visions.

Tibor Joanelly: And these megastructures became more and more extreme. He developed ever more audacious structures, most recently with a design that at a height of 4,000 meters would have been over twice as high as Frank Lloyd Wright’s The Illinois One Mile Skyscraper.

What would you say is typical of Zalotay’s oeuvre?

Tibor Joanelly: He always trod a narrow line between pragmatism and utopia. Order and chaos collide in his ideas that are between constraint and surplus. The manic meets something meticulously thought through.

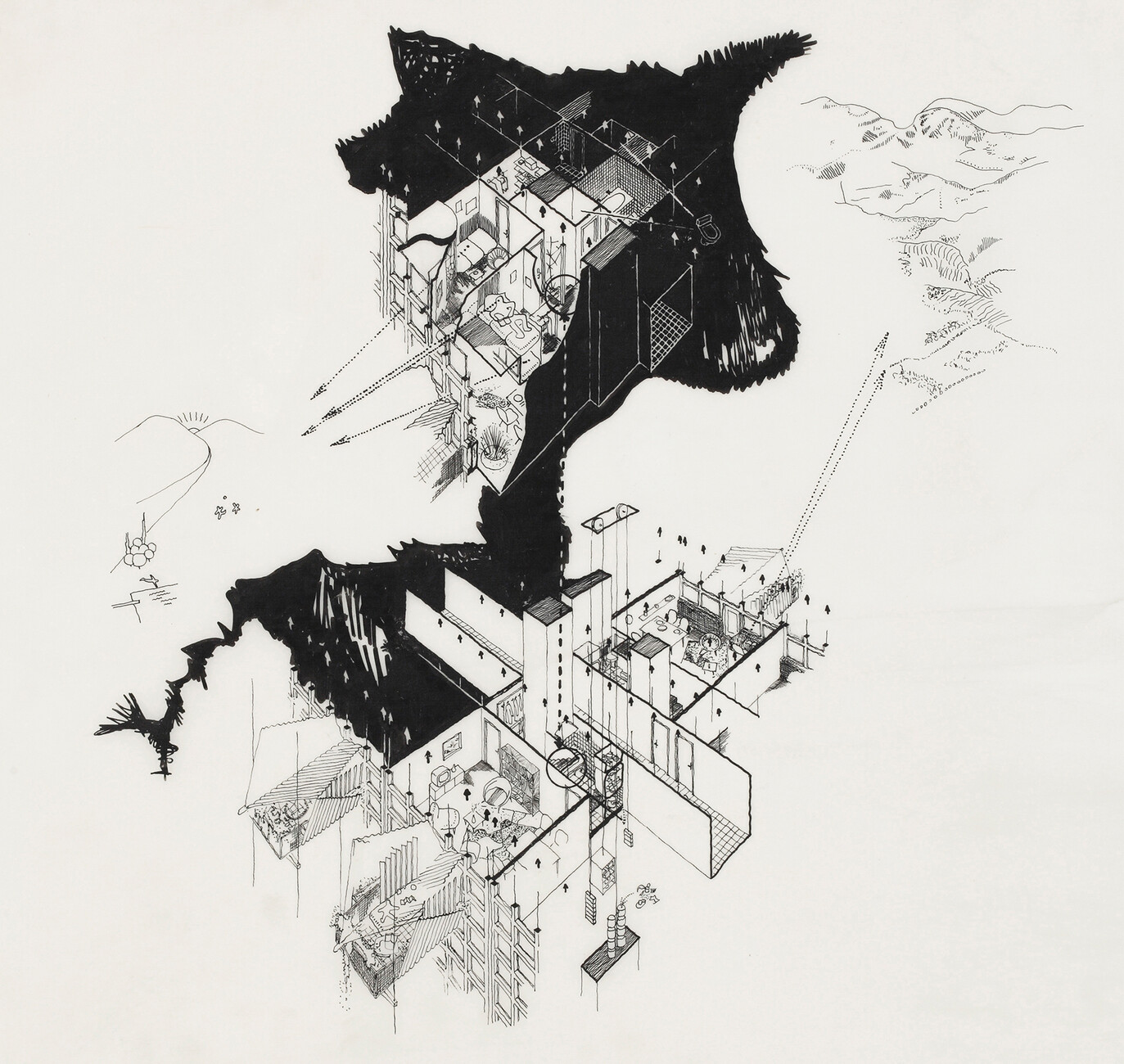

Something else that seems manic to me: his late drawings, large-format, artful hidden-object drawings, in which hand-written postulates meet building constructions.

Tibor Joanelly: They are building instructions for a better world – construed and thought through down to the last detail. I like to imagine him maybe sitting on a jib of his DNA spiral tower and elaborating threads of ideas.

Elemér Zalotay: Manic Modern

Runs until May 15, 2021

BALTSprojects

Bernerstrasse Nord 180, 1st floor

CH-8064 Zurich

Elemér Zalotay (born 1932, Szentes, Hungary; died 2020, Worben, Bern)

Elemér Zalotay studied architecture and in 1957 graduated from the Budapest University of Technology and Economics. Shortly after his studies he became known for a three-kilometer long “linear tower block”. Before eventually emigrating to Switzerland in 1973, he designed several sensational buildings in the west of Hungary including the Sputnik Observatory in Szombathely. In Switzerland, Zalotay worked for several renowned Bern architects before setting up on his own studio. He became known in Switzerland for the house he built himself in Ziegelried and that he continued to work on from 1979. It was placed under a heritage preservation order in 1993.

Apart from this building there are no other works in Switzerland that can be ascribed to Zalotay alone. The architect refined his design concepts on paper. His projects were published in internationally acclaimed specialist journals and much discussed. Zalotay was the winner of the Molnár Farkas díj (the highest distinction for architects in Hungary), an honorary member of the Széchenyi Academy for Literature and Art. He died after a brief illness in an old people’s residence close to Biel. A comprehensive monograph on his work is due for publication in 2022.