READING EDUCATES

Too late for sedate

A few years ago Arte screened the hit Danish series “Borgen,” beaming the ins and outs of politics and intrigue in Denmark into our homes – and with them a view of the office of the fictitious Danish Prime Minister Brigitte Nyborg – with sofas by Børge Mogensen (1914-1972).

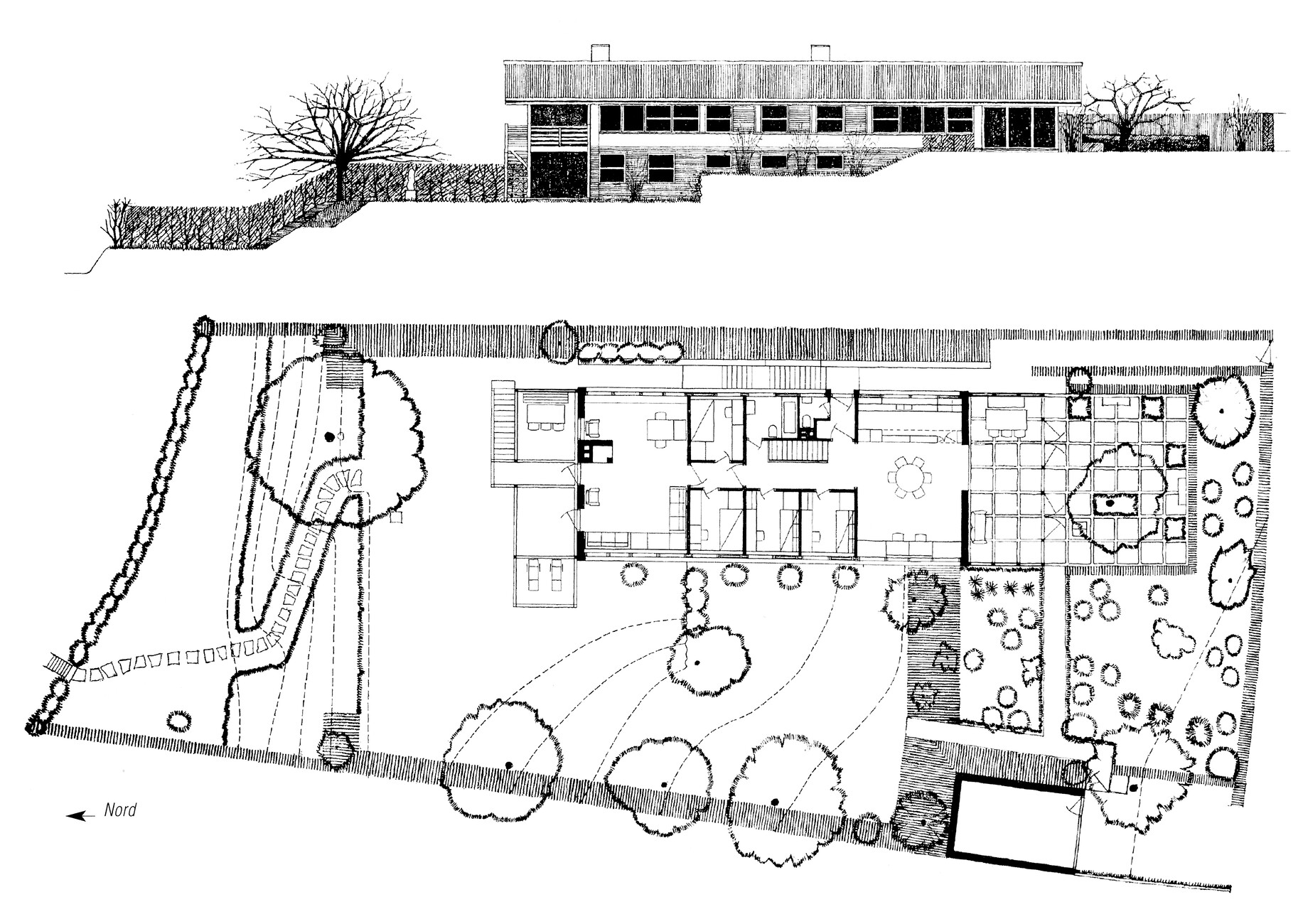

The architect and furniture designer is a veritable institution in Denmark and it is no coincidence that his “2213” sofa is fondly called the “embassy sofa,” as it is indeed to be found in the Danish State Chancellery, in ministerial offices, and in countless Danish embassies the world over. Mogensen designed it in 1962 for his own living room at his home in Soløsevej, but it has long since emerged as one of his best-known pieces. On closer inspection you notice that even this late design contains elements of Mogensen’s early work; his plain, functional and unpretentious approach to design which was so strongly influenced by his teacher Kaare Klint. For example, the “2213” is reminiscent of Klint’s box-like “Barcelona sofa” which he created for the 1929 World Expo in that city.

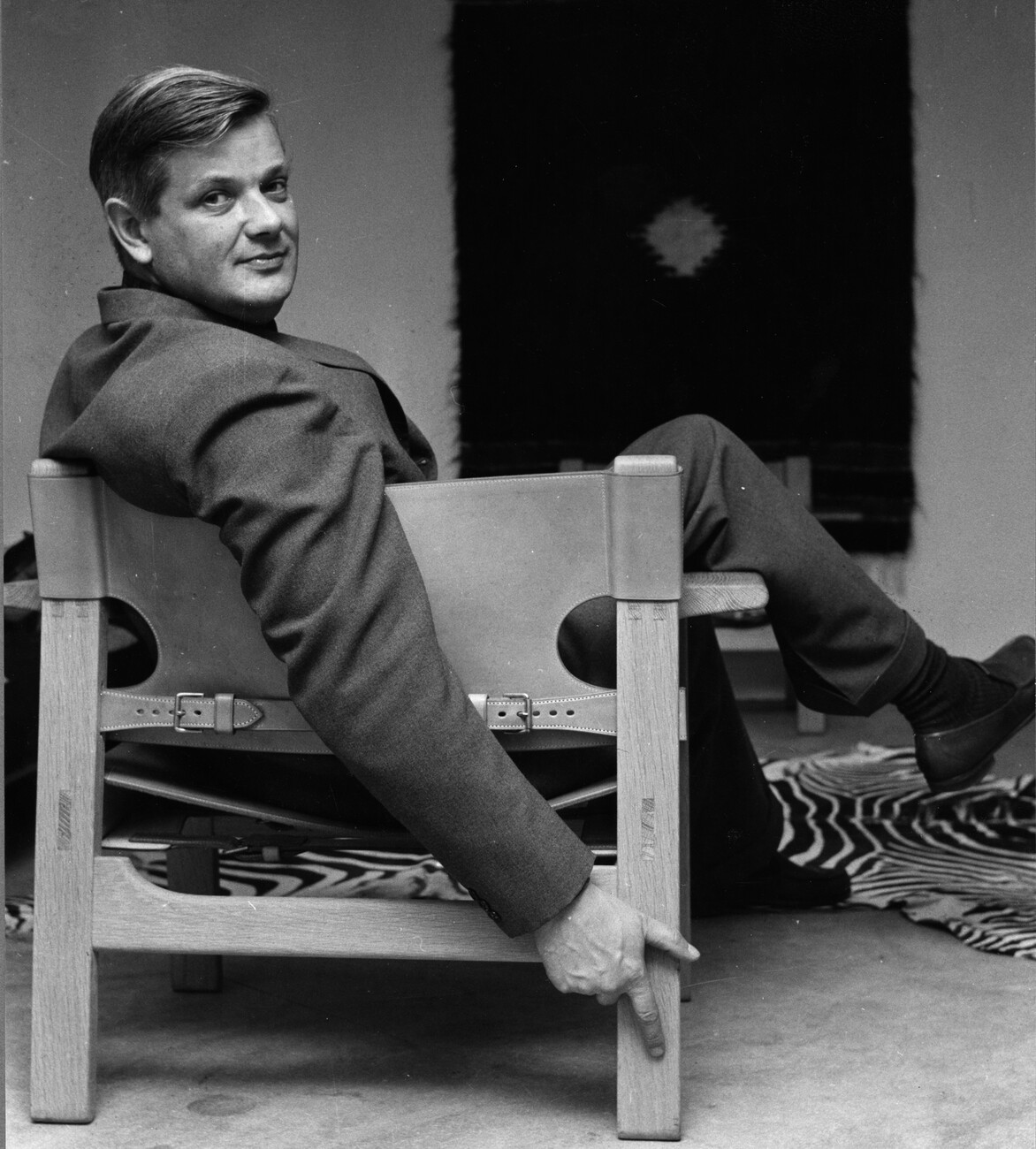

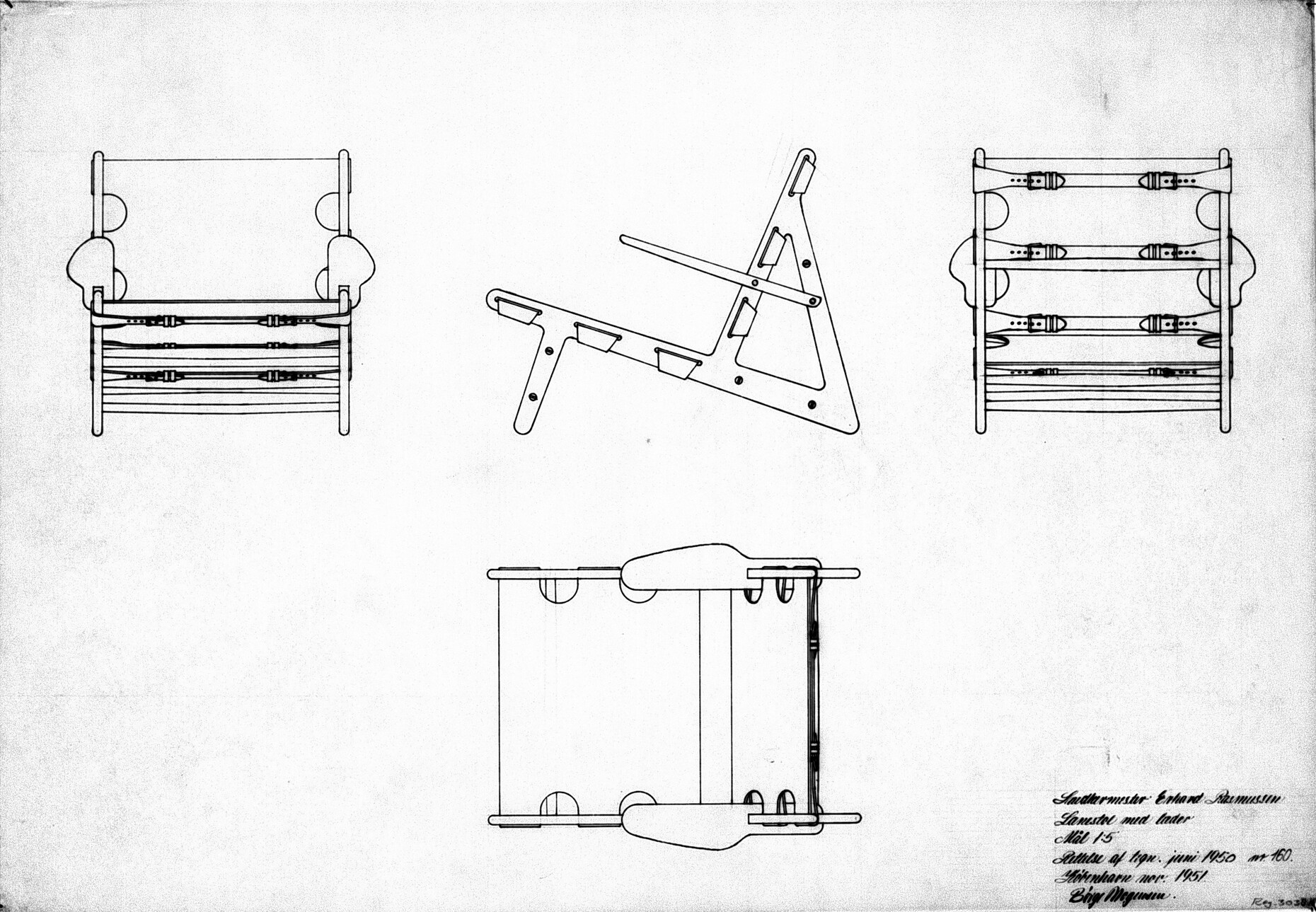

Michael Müller’s monograph “Børge Mogensen: Simplicity and Function,” which came out in the wake of the jubilee exhibition at Kunstmuseum Trapholt marking the 100th anniversary of the designer’s birth, goes a lot further however. It offers an outstanding overview of the oeuvre of this important furniture creator and places him in the Danish context between industrial production and cabinet-making. Workshop drawings, sketches and images of furniture as well as photographs of Mogensen’s house and his everyday life provide an insight into the world in which he moved.

Functional and flexible instead of sedate

Mogensen attended an arts & crafts college from 1936 to 1938 and there met cabinet-maker Hans J. Wegner, who was almost exactly his age; they worked very closely together for the first few professional years and were to become friends for life. After his time at college, Mogensen moved on to the Art Academy, to the furniture class in the Architecture Dept. One of the lecturers and later professor there was none other than Kaare Klint, the man who was to influence an entire generation of Danish furniture designers, among them Hans J. Wegner, Finn Juhl and Mogensen, who collectively created what we today call “Danish Modern.” They all set out to replace the heavy, opulently upholstered furniture of the sedate “Klunke style” of the late 19th century with perfectly crafted, light, flexible and often modestly priced furniture.

When reading the forever informative and objective description of Mogensen’s career and his designs, five aspects strike the eye that shaped his oeuvre: the adherence to a strict form of functionalism, such as that Kaare Klint taught; the idea that design should improve on historical examples; the strong sense of the quality and beauty of wood as a material; his advocacy of plain, affordable and often multifunctional furniture; and the clear system of proportions Klint tried out as early as 1917 with industrially manufactured furniture and which Mogensen adopt

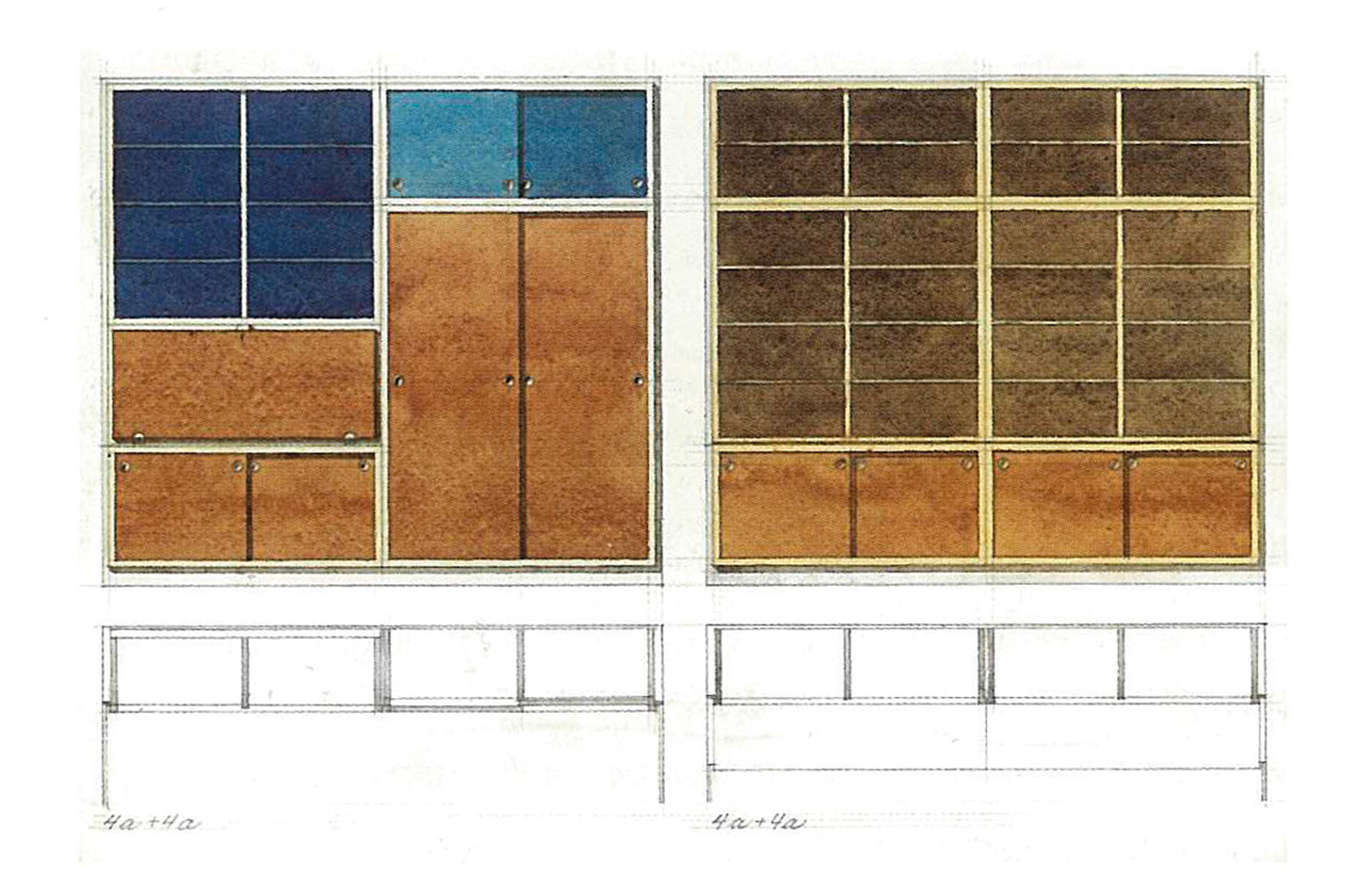

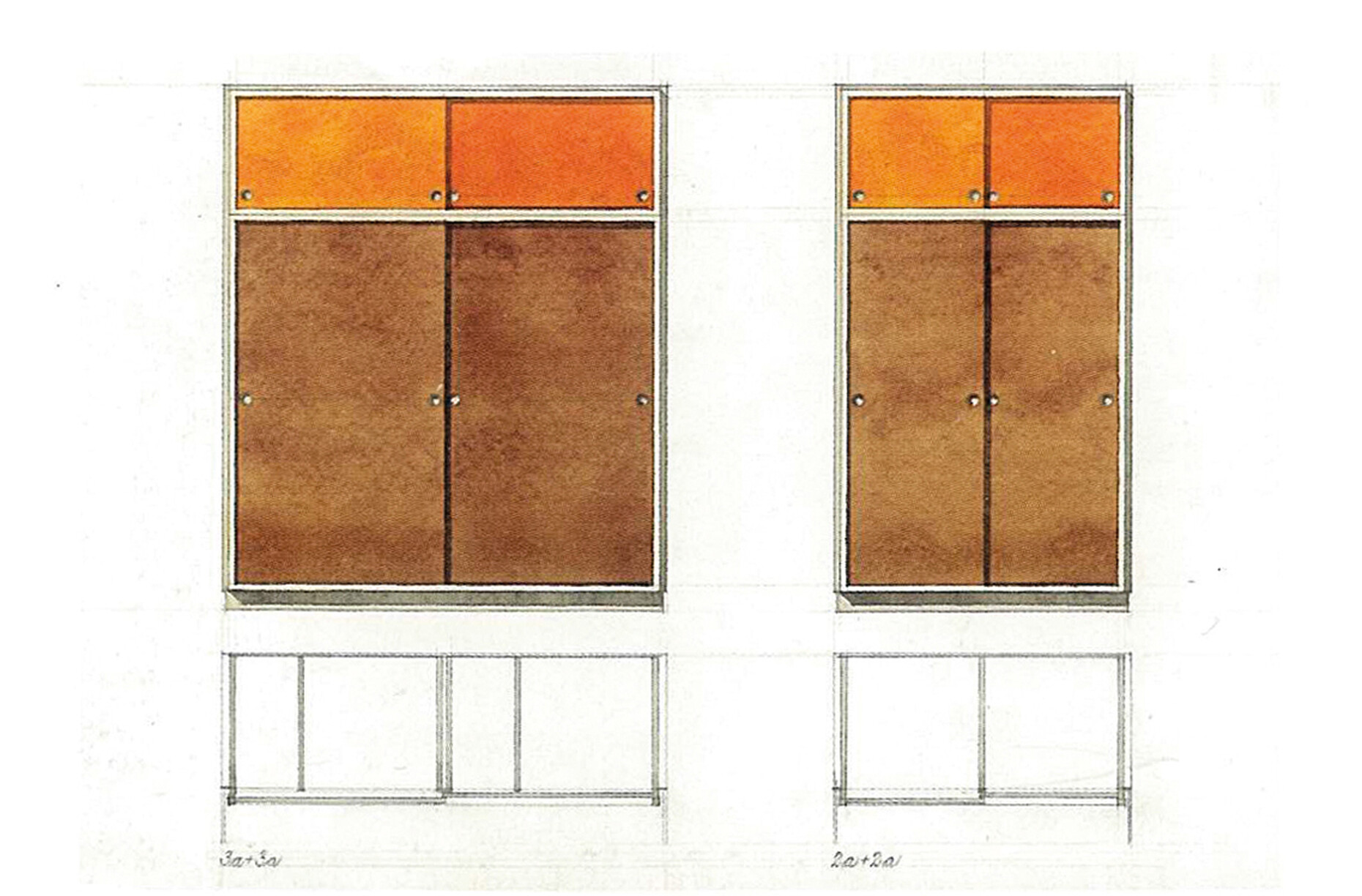

Every spoon and every shirt was carefully measured

When it came to detailed studies with measurements, while still in the furniture class at the Art Academy Mogensen proved to be an especially conscientious student when it came to precision measurements of cutlery or a tableware set such that the measurements, transformed into standardizing units, could then form the basis for the size of a sideboard or cabinet for the dishes. As late as the 1950s, when he was busy with architect Grethe Meyer working on the “Boligens Byggeskabe” cupboard system, Mogensen’s exact and detailed drawings show how carefully he calculated each drawer and each distance.

Finis for frills

Børge Mogensen’s career started in 1942 at the tender age of 28, namely as director of the furniture design office run by FDB, the association of Danish consumer cooperatives, for which he then proceeded to devise an entire furniture range. “Like many other functionalist furniture designers,” Müller writes, “Børge Mogensen turned his back on the old Klunkestil furniture and what he called ‘meaty furniture sets,’ those bureaus with all manner of frills, the massive dark sofas that took up precious space and were not designed with human proportions in mind. ‘There is no reason why a sofa set must look like a ham pumped full of water,’ he chided and added: ‘Why should a small apartment be filled to bursting with ham-fisted, impractical furniture if one can instead invest in cupboards and tables that are less massive and are so ingenious that they provide more space and can be used in many more ways?’ With their plain and rationally combinable items instead of massive furniture sets, Mogensen and FDB sought to focus the design work on the users, the people.”

Improving what already exists

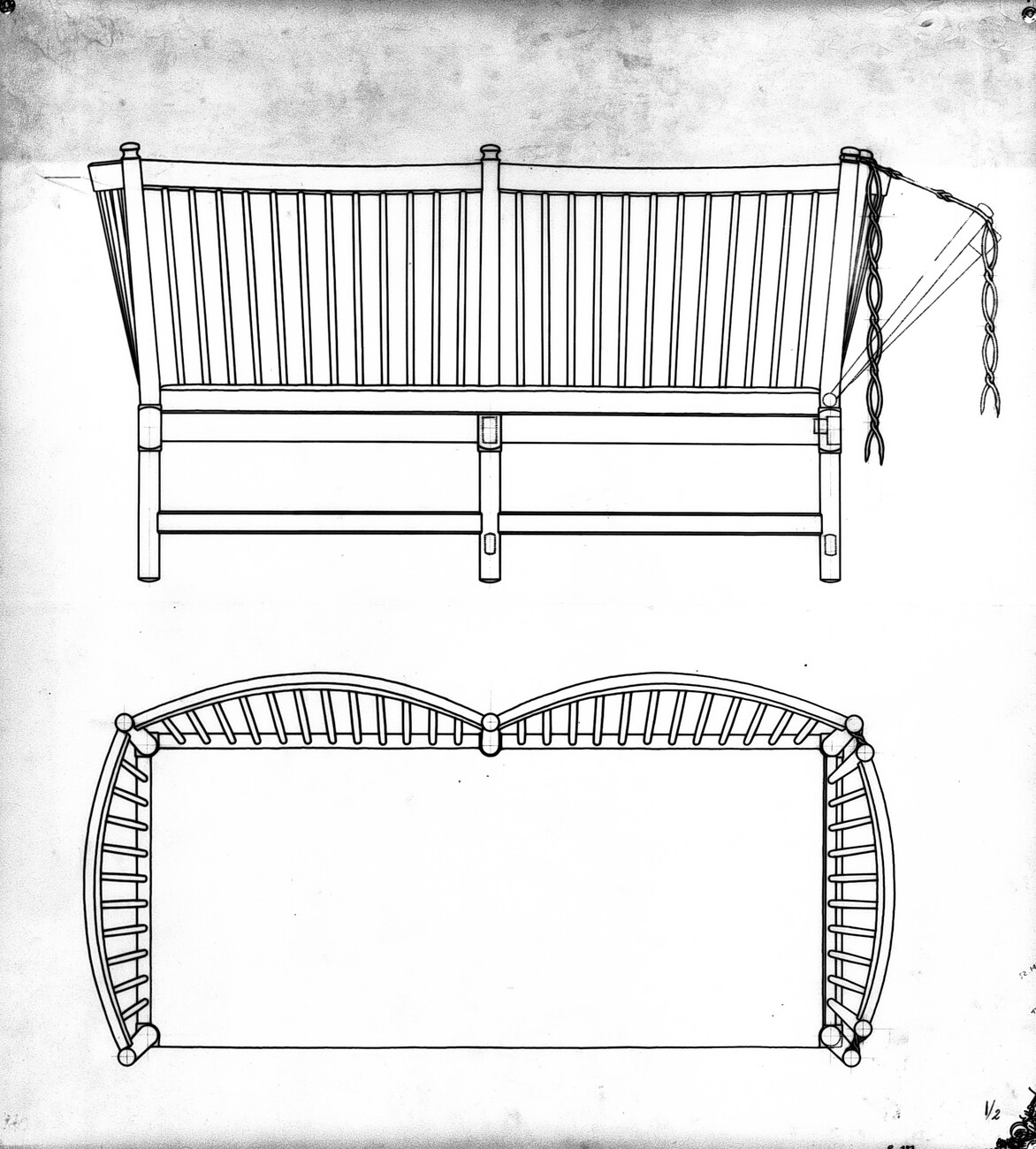

Throughout his career, Mogensen drew inspiration from historical furniture types, advanced them and improved on them, as can be seen, for example, from his “J39” dining room chair, which he designed in 1947 for the FDB and which constitutes a simplified version of Kaare Klint’s 1936 “Church chair.” Simplification was the maxim when in 1945 he and Hans J. Wegner together designed the interior of a two-bedroom apartment for the annual Guild Show. Among other things, Mogensen contributed a two-seater “spoke-back sofa” made of mahogany that was later to become one of his best-known pieces.

Inspired by chaise longues, daybeds and Windsor chairs

The “spoke-back sofa” is remarkable for several reasons. First, Mogensen drew his inspiration from French chaise longues, English daybeds and Windsor chairs, combining their respective properties. Second, the settee shows how much the Danish taste in interiors was still defined by sedate furniture. The Fritz Hansen furniture factory started producing the sofa, but swiftly discontinued it when only 50 units sold. The sofa only really became a success when Fritz Hansen relaunched it in 1962: The general public’s taste had since changed. And now the “spoke-back sofa,” usually with woolen checkered upholstery covers courtesy of Lis Ahlmann (with whom Mogensen loved collaborating) became a permanent fixture in many Danish homes. It was especially popular among teachers and academics, who found it not only comfortable, especially when the one arm was folded down, but also because of the mindset that the design expressed.

Junk and trash at outrageous prices?

Mogensen, Müller asserts, “also had a very engaging, albeit very direct manner. He chatted and discussed things with charm and verve, be it about professional or personal matters. However, his pragmatism and occasional fierce temper masked a very sensitive and complex personality. He never disguised his opinions, especially when it came to furniture.” In 1962, he turned his ire on the entire Danish furniture industry. In a lengthy text co-authored with his friend the architect Arne Karlsen and entitled “Absurd utilitarian art,” he not only polemically criticized the latest products but named names in the process. He accused the design scene of having turned its back on that Danish design tradition which had coined the term “Danish Modern” and of having neglected function in favor of sculptural forms.

The accusatory tone of the text was set by starting with the following quotation from Poul Henningsen from 1927: “Dear Friends of Arts & Crafts! How can you expect that we continue to respect you if art is used as a cover behind which swindle and sham are rampant? As long as all modern tasks still wait to be solved? We do not possess a single rational water beaker, plate, washing-up bowl, spoon, knife or fork. Yet the homes of the better-off in society are dripping in junk and trash sold at outrageous prices. (...) Pull yourselves together and tackle things, create things that people enjoy using in everyday life! Throw away your artist’s hats, throw away those artist’s cravats, get into your overalls!”

The examples Mogensen and Karlsen gave for such “junk” are: cutlery by Jens H. Quistgaard, not to mention furniture items by Verner Panton, which Mogensen felt were “simply gimmicks.” Panton’s “Heart Cone Chair,” with the backrest reminiscent of a heart, and also Mickey Mouse ears, was suitable, Mogensen said, perhaps as a joke for a few hours or for a drink at the bar, but not for everyday use. The authors did not have to wait long for the responses.

It is quite astonishing that now this controversy is definitely topical again. Today, designers and design students face the same dilemma, although the zeitgeist now loves to think you can switch back and forth between function and art.

If one browses the monograph, which is replete with insightful photographs and drawings, and examines furniture such as the “Øresund” series storage system Mogensen developed for Swedish company Karl Andersson & Söner, or the “Boligens Byggeskabe” (which basically means “fitted cupboards for the apartment”) that were, thanks to exact measurements, perfectly sized for everything to be kept in them, then one fact sticks out: The perfectly developed cupboard system sold well, but, since Mogensen refused to compromise on materials and finishing, was too expensive for young people to be able to afford. “Would it not have been possible,” Müller asks with a view to Mogensen’s championing of social and democratic design, “to give young people something practical that they could also afford?” What he fails to mention is that precisely that is what IKEA later did with similar, but far cheaper systems.

This did not deter Børge Mogensen. What he set out to achieve in all of his designs, as he said in an interview, was to “create things that serve people, that focus firmly on people, instead of forcing people to adapt to things at any cost.”

Børge Mogensen – Simplicity and Function

By Michael Müller

240 pages, hardcover, 201 ills.

Verlag Hatje Cantz, Berlin 2016

ISBN 978-3-7757-4211-5

EUR 49.80