BIENNALE ARCHITETTURA 2018

Ten little exercises in metaphysics

The Church essentially withdrew from the island of San Giorgio Maggiore in the Venetian Lagoon 200 years ago. Yet up until it was disbanded during the Napoleonic occupation, a rich and powerful Benedictine convent was located here. After the end of the Venetian Republic, all that remained in terms of places of faith was Palladio’s enormous church. The rest of the monastic island was soon used as military barracks and increasingly fell into decay until the complex was restored and turned into a research center at great expense by the cultural foundation of industrialist Vittorio Cini in the 1950s and 1960s. In doing so, Fondazione Cini had a number of 19th-century buildings demolished. The resulting construction rubble was used to enlarge the island. A small amphitheater, now unfortunately in a state of disrepair, was built on the newly created land according to plans by Luigi Vietti and Angelo Scattolon, and a small wood was planted. This grove is where the Apostolic See has erected ten chapels as its contribution to the 2018 Architecture Biennale, curated by Francesco Dal Co and Micol Forti and in collaboration with some of the most renowned living architects.

“Locus amoenus” is actually a term that comes to mind in the small woodland on the lagoon. Trees cast their shadows on the paths, at the ends of which the blue water glimmers. The Lido can be made out across the water, as can the islands of San Sérvolo, La Gracia and San Clemente, the Giudecca. The small woodland is a place of refuge for all those making their way across from the Giardini, the grounds where the Biennale is held. Here you will find no onslaught of information as greets one in many national pavilions, no pushing and shoving in order to cast a glance at the contributions, and no kilometer-long treks are required in order to gain an overview. And yet, having completed the stroll across San Giorgio Maggiore, one leaves having seen the ten perhaps most important contributions to the Architecture Biennale of 2018.

Sculptural structures

Instead of limiting the architects with a motto, an exact definition of task or objective, the curators took a different path – they named a role model: Gunnar Asplund’s woodland chapel (Skogskappellet), which the Swedish architect built at the beginning of his career between 1918 and 1920 on the new Stockholm woodland cemetery (Skogskyrkogården). It is a simple, small building, and many of its elements draw on the Romantic Classicism of the early 19thcentury. The curator pointed in particular to Asplund’s inclusion of the forest into his design as something worth emulating. And indeed, the interplay between chapel and environment is the decisive element to many of the ten new constructions on San Giorgio Maggiore and is at times taken so far that the boundaries have become entirely blurred.

Carla Juaçaba, for example, has reduced her design to a large-scale metal sculpture – a chrome-plated steel girder, bent at a right angle, the leg of which juts out vertically from the ground. Two projecting traverse struts create an upright and a horizontal cross; seven concrete sleepers provide both support for the large steel girder and seating for visitors. Here, nature is the house; while the ostentatious presence of the cross and the benches installed in front of it make the sacred character of the simple construction clear.

Javier Corvalán from Paraguay departs from the notion of a house of God even more radically. In reference to the small rotunda in Asplund’s Stockholm cemetery chapel, Corvalán hangs a ring spanning almost eleven meters in diameter and three meters in height freely from a tripod of steel tubes. The ring hangs at a slight angle, allowing visitors to walk below it on one side while it hovers but a mere half meter above the ground on the other. It creates a space that is both open and enclosed, while it is only the three-dimensional timber-beam construction mounted on the tripod, a riff on the cross symbol, that implies its clerical use.

Gold duct and wooden lattices

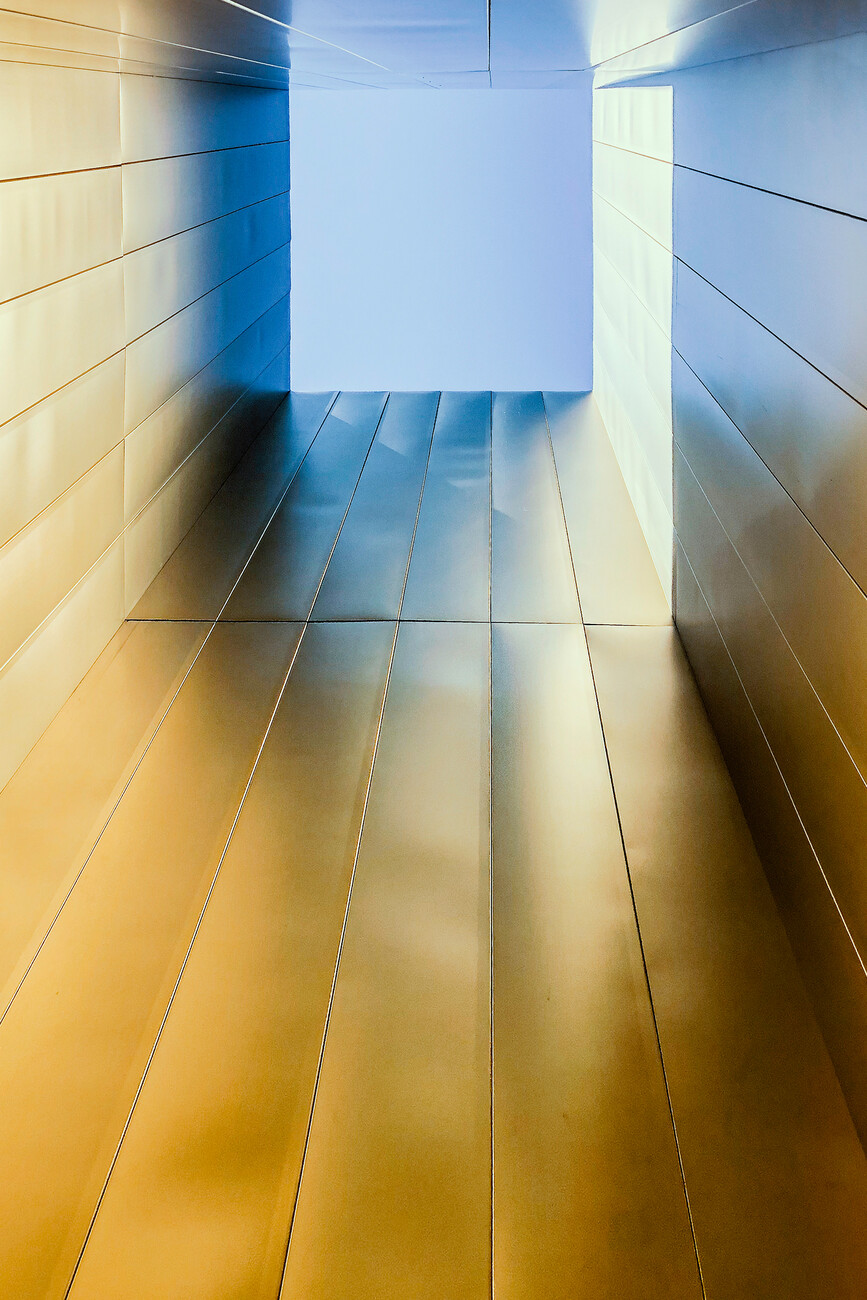

The design by Sean Godsell is much more closely linked to Christian rites. The Australian has created a lockable field altar of sorts for Venice. Like a market stall, it can be fastened using latches on the four outward-facing sides. The altar sits below a rectangular duct lined in gold, which steeps the altar and celebrant in a golden light – creating a small Baroque sacral spectacle that requires just a few simple actions in order to be packed up for travel. Francesco Cellini’s design appears similarly portable. It consists of two intersecting metal bracket shapes, of which the larger defines the space, while the smaller encloses altar and ambo in the center of the chapel.

Norman Foster’s chapel takes the shape of an elongated and winding room. Constructed using cross-shaped steel girders and braced wooden lattices, it leads visitors towards a wonderful view of the lagoon. Here, the wooden latticework of the walls opens up, and all that stands between viewer and nature is the altar – a built reflection on shelter and openness, space and environment.

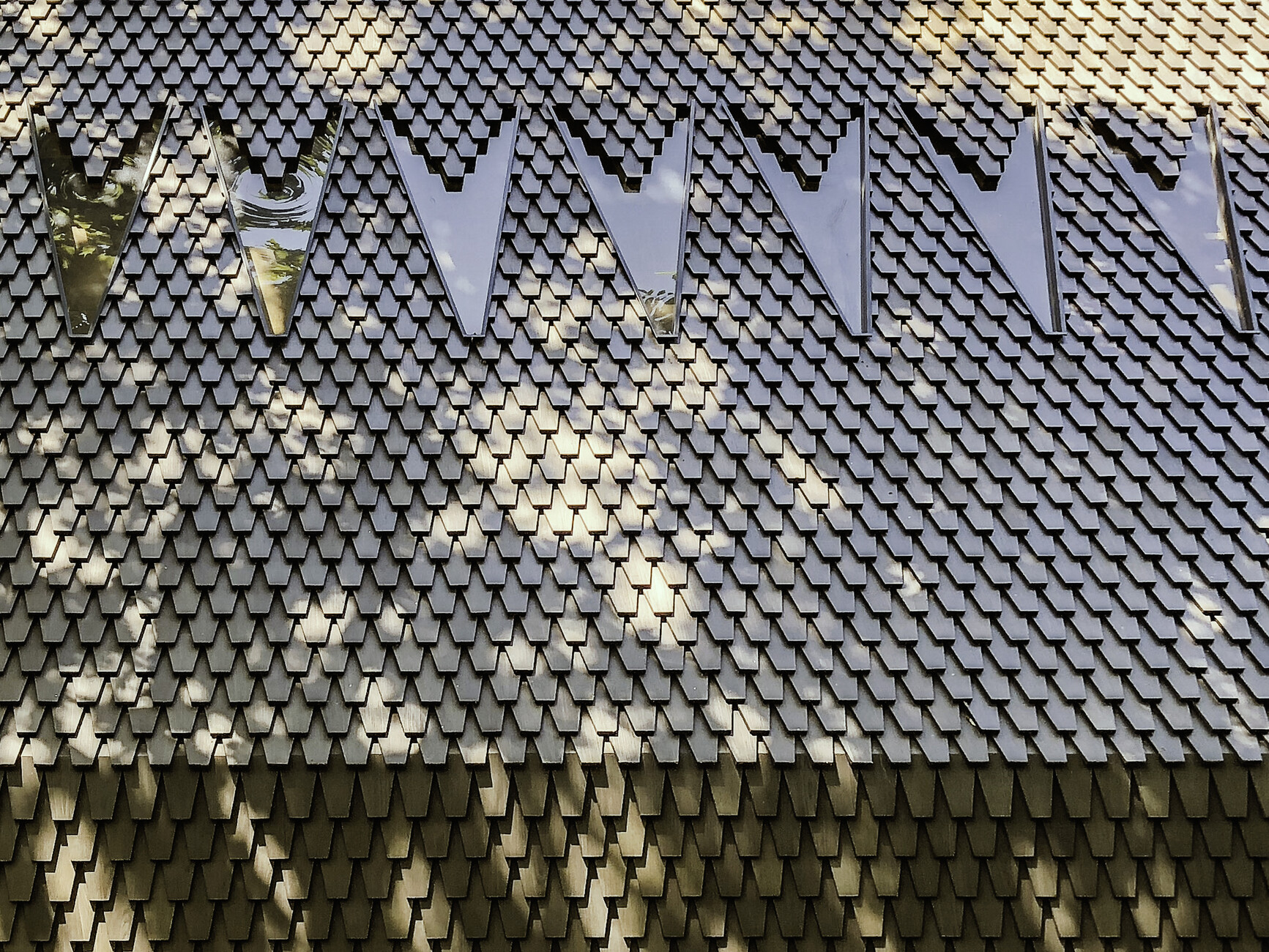

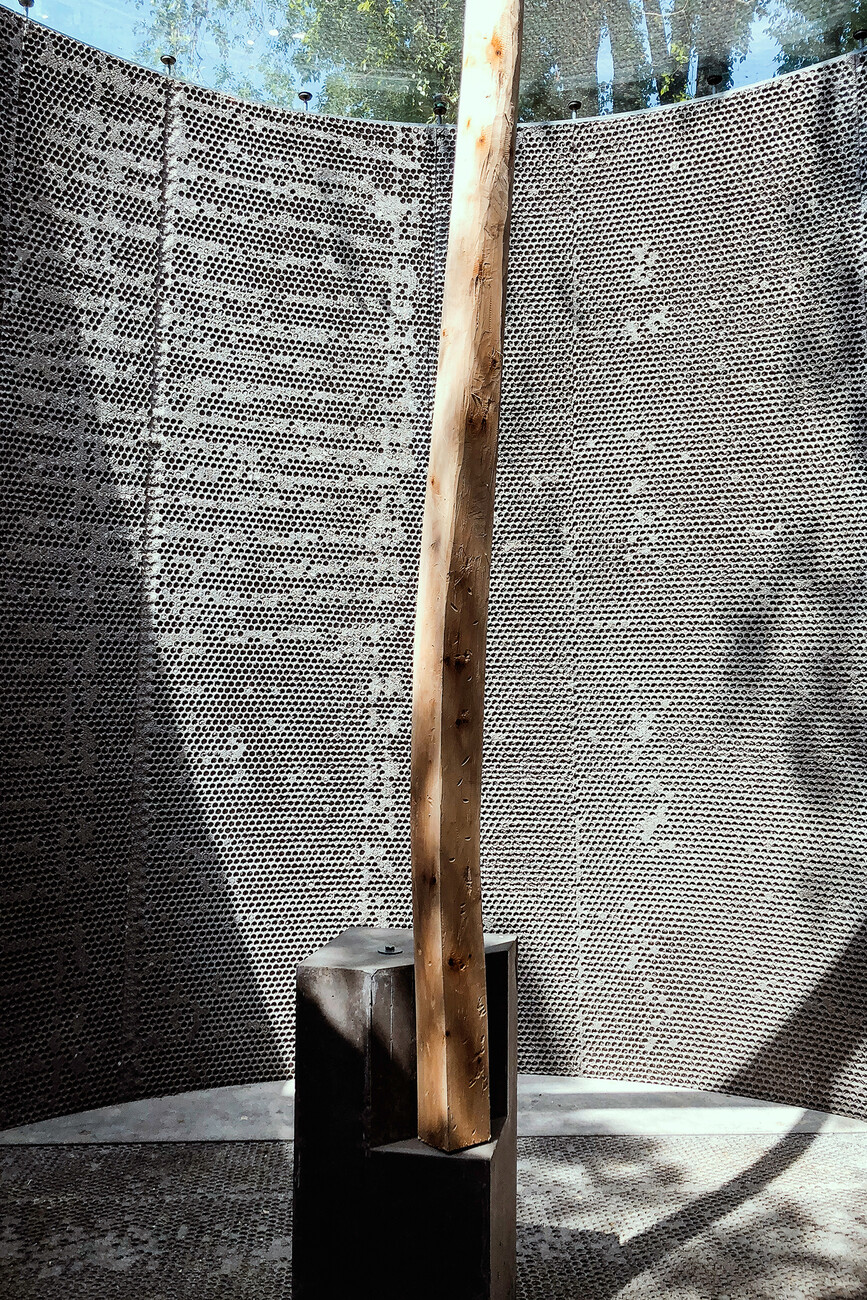

Other designs conform more strongly to the character of a solid building, even if they are, as in the case of the terracotta architecture by Ricardo Flores and Eva Prats, more of an oversized piety column (however featuring a circular window cut-out instead of an image of a saint). Closest in type to the classical chapel are the small buildings by Andrew Berman, Smiljan Radic and Terunobu Fujimori. Berman has created a chapel with a triangular floorplan. The actual prayer room, lit only through a skylight at the very tip of the room, is preceded by a small portico that serves as a lounge for visitors. The special charm of Radic’s small, glass-roofed rotunda comes from the materiality of its interior walls, where a cellular foil was placed in the cement. Fujimoto created the typologically most conventional building: A small wooden house with benches in front of a large cross. Yet drawing on his formal and material repertoire developed over many years and lighting design that is as simple as it is impressive, he might have just managed to produce the space best suited for contemplation.

Edouardo Souto de Moura, in conclusion, has realized an archaic-looking cell made of large blocks of Vicenza stone. These form the walls with a circumferential bench inside the space. The roof is fashioned out of two enormous stone slabs and covers part of the interior. Different processing techniques have been employed to treat the surface of the honey-colored stone, enlivening the simplicity of the monumental structure, the interior of which appears removed from the world through the enormous solidity of its walls.

Churches or meditation rooms?

This is not the first time San Giorgio Maggiore has been used as a location for radical architectural experiments. The audacity of Andrea Palladio, who created the plans for a new build of the monastery chapel for the convent of San Giorgio in 1565-66, is hard to overestimate. Being at the peak of his career at the time, he had of course produced numerous palaces and villas on terraferma, the estates owned by Venetians on the mainland, as well as the façade of the church San Francesco della Vigna in the city of Venice. But with his construction on San Giorgio Maggiore, opposite the Doge’s Palace, he set out to fundamentally change church-building not only in Venice, but in the entire Western world. He eschewed the detail, polychromy and rich ornamentation of the Venetian Renaissance, along with Mannerist extravagancies as put forward by the likes of Michelangelo or Giulio Romano. The façade based on ancient temples instead exudes rigor and majesty. The classical shapes are used on a far more monumental scale than before – also because Palladio wanted to achieve an impressive long-distance effect for his building when seen from the city. Yet the master builder was not nearly as free, so able to design without restrictions, as his successors: the architects of the ten chapels.

Of course, religious architecture always had to follow the strict rules of liturgical practice. Nowadays we are unfortunately prone to forgetting that the structural elements of a church – sanctuary, chancel, side chapels, ambulatory, galleries – were not original inventions by architects, but built for precisely defined functions. The same holds true for every chapel. Palladio, for example, had to take into account in his design that the church would be housing the monastery’s most important treasure (and main source of income), namely the relics of protomartyr St. Stephen. This made it not only an important pilgrimage site, but also the location of a large procession led by the Doge on the Feast of St. Stephen. It was important to guide these streams of people through the building, and to lead them to their respective destinations. Had he not fulfilled this task, his revolutionary structure would not have been built.

It is then perhaps all the more surprising that Gianfranco Ravasi, the Curial Cardinal, President of the papal Culture Council and spiritual father of the Biennale project, completely factors out the liturgical aspect in his introduction to the accompanying catalog. In fact, the building type of the chapel appears in his text as an interdenominational, even trans-religious place of reverence and contemplation of sorts. Ravasi sees light and nature as an ideal symbol of the divine, while the allegorical, narrative communication of specific messages of faith evidently no longer plays a role. This is remarkable also insofar as the holy figures found in so many Catholic chapels point to the patrons in question as mediators and advocates for believers with the Almighty. As previously mentioned, the veneration of saints and the associated veneration of relics is the second-largest determinant of Catholic sacral architecture alongside the liturgy. The buildings now erected on San Giorgio Maggiore have been liberated from all of this. In the most official of contexts, the Catholic Church releases “its” architects from essential conditions developed over centuries by theological theory and practice. Whether this constitutes a fundamental change in direction remains questionable. Maybe the Church is simply following the zeitgeist? After all, some of the best-received chapel buildings of recent years, such as Peter Zumthor’s Bruder-Klaus-Feldkapelle in the Eifel Mountains, can no longer be unambiguously identified as Christian structures. And in the short accompanying text for his design, Francesco Cellini describes himself as an atheist, and his building less as a chapel and more a reflection on a chapel. All of this goes to show just how fundamentally the question of Christian-Catholic religious architecture is being negotiated in the early third millennium after the birth of Christ. This alone makes the Vatican’s contribution the most important of this year’s Architecture Biennale.