‘Photography works like a window into our memory’

Katharina Cichosch: Mr Ortiz, can you remember the very first building you ever photographed?

Aitor Ortiz: Yes, I remember it very well, it was in the early 90s, an abandoned hospital that was never completed.

You are an architectural photographer in two senses: classic documentary, for example for architectural publications, and with a strongly artistic approach. How do the two approaches come together for you - or are they two completely separate bodies of work?

Aitor Ortiz: The professional intention is not the same, but they are close in their common intention to show the feeling in a space. In professional work, the building is information to be documented, a work that has usually been recently completed, with its motivations, its context, etc.; a whole series of requirements to which the architect has responded and which I must try to represent; whereas when I work on my own works, I usually choose buildings that are anonymous or whose authorship is more or less diffuse. These are structures that are entirely at my disposal to create a new meaning that often has nothing to do with their original function. However, there is a kind of promiscuity, sometimes I use images from professional works to develop them in the others. The intention may be different, but the eye looking at the space is the same.

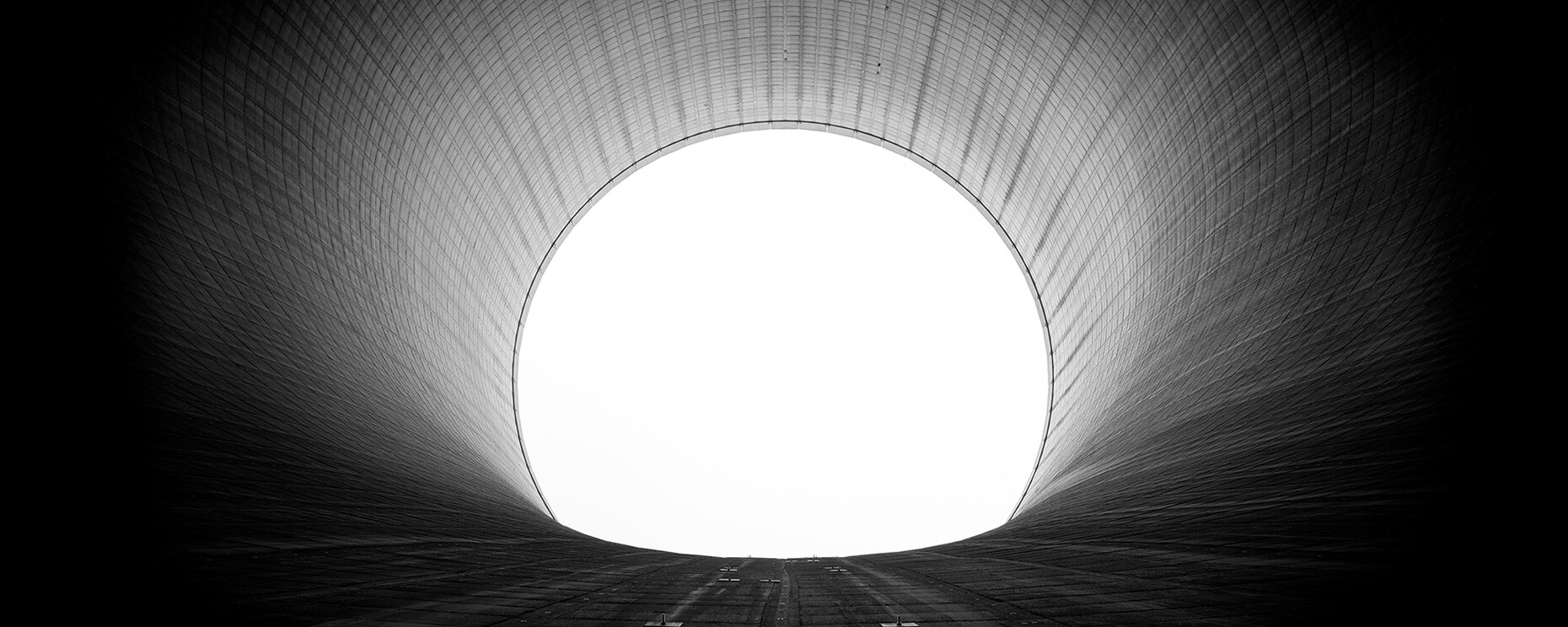

In your photographs, as recently shown at your gallerist Heide Springer House of Galleries in Frankfurt, you get very up close, focussing on individual structures, components, details or viewing them from an unusual angle.

Aitor Ortiz: Resolution is closely linked to scale. The part of architecture that interests me the most is the structure, the skeleton, the essence and related aspects such as modularity, sequence, fragmentation... These aspects have no scale, and I have photographed them in large buildings and in small pieces of metal left over from the machining of an industrial element.

This could be seen as a demystification of architecture. The images refuse the grandiose long shot.

Aitor Ortiz: The isolation and decontextualisation of the architecture I photograph questions its functional and constructive meaning, and the avoidance of long shots is intentional. In photography, what the image shows us is just as important as what we don't see and have to reconstruct with our imagination. If you photograph a ten-storey building in its entirety, it is a ten-storey building. But if you limit the image section to the 9th floor, your brain will try to imagine a 10, 20 or 50-storey building.

Your images are therefore free of anecdotal knowledge. Or rather, we can't know that much about them. As a result, something specific happens when we look at them: in the limitation, the view seems to become free - the correct resolution, as you say, doesn't matter.

Aitor Ortiz: A photograph works like a window into our memory, so that each of us reconstructs the image from what is seen in the picture, incorporating our own memories and experiences to complete the scene. My work is not strictly documentary, and I don't usually give any information about the places I photograph because I consider that anecdotal in each image. But in my creative process, working in Bilbao, a city with a strong industrial past, has determined my photographic work as a whole.

Similarly in your current exhibition ‘Between archetypes and artifacts’ in Madrid, whose pictures show detailed shots of aluminium, steel, spirals and structures. People are not visible in your photographs. Is it a dystopian, post-human world - or are they present in the artefacts you mention in the title?

Aitor Ortiz: This exhibition takes us back to the industrial past that characterised the world in the 20th century, but also to the discarded materials that this work produced. So what is shown here is not the visible face of the techniques and technologies, nor the finished products or the language of design, but what happened behind the scenes: the aesthetics not of the consumer goods, but of the processes themselves, the forces, shapes and surfaces that moulded them. Plates and frames, parts and cogs, chips and splinters - removed from their original context and function - are now presented as objects that evoke perceptions and challenge them at the same time.

With your work, you naturally move in three-dimensional space, which is flattened into the second dimension. Until the photograph is then exhibited. What role does this space, the setting of an exhibition, play in your work?

Aitor Ortiz: I believe that two-dimensionality is a limit to the perception of a space, but the greatest limit of photography is the point of view, it is unique. My work is always about the relationship between the photographed space or building, the scale and position of the photograph in the exhibition space and finally with the viewer. The photographs are about architecture and are sometimes inscribed in the specific architecture of the exhibition space. My intention is to make the photographic works ‘grow’ in a three-dimensional space; by introducing real scale and real light, the works change our perception of architecture.