Every now and then photographers might resort to their antiquated pinhole cameras to capture the stylized geometric shapes of a new architectural trend. At times these simple devices, which offer little precision and hence lack focus, can be of advantage – because they serve the photographer’s intention. For several decades now Josef Koudelka has been an avid advocate of this technique. Be it his portrayal of Eastern European brownfield landscapes in “Black Triangle” or his coverage of gigantic industrial monuments in “Chaos”, the Magnum photographer has always been fond of seeing the world through wide-angled lenses. A panoramic camera is quite heavy and each film produces just four 6 x 17 cm shots, so it’s far too unwieldy to be a photojournalist’s favorite piece of equipment. Consequently, the images Koudelka contributed to the 1992 anthology “Beyrouth Centre Ville” stood in stark contrast to the pictures photo essayist Robert Frank, photojournalists Raymond Depardon and René Burri, and architectural photographer Gabriele Basilico produced on their rambles through the metropolis on the Mediterranean coast, which was heavily scarred by the civil war.

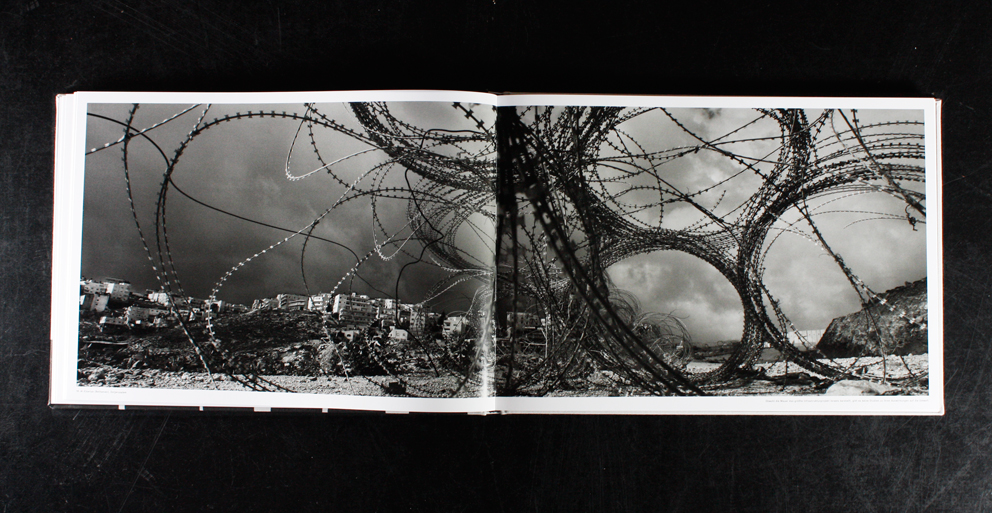

What better person to capture the oppressiveness of roadblocks, barbed wire obstacles and sandbag barricades against the backdrop of deserted ruins through coarse-grain, black-and-white images, than Koudelka and his panoramic camera. Creating full frontal images with a central vanishing point the camera fosters a sense of distance. And focuses the viewer’s attention on overwhelming architectural monuments as a somber manifestation of the consequences of military aggression.

The question of who was “responsible” for this state of affairs, however, seemed of lesser concern to the photographer. Didn’t all parties to the civil war use violence in equal measure? As to the causes of brutality in everyday civic life and what effects such acts have, he evidently felt that the shattered cityscape, deeply furrowed by exploding shells and bomb craters, would simply speak for itself.

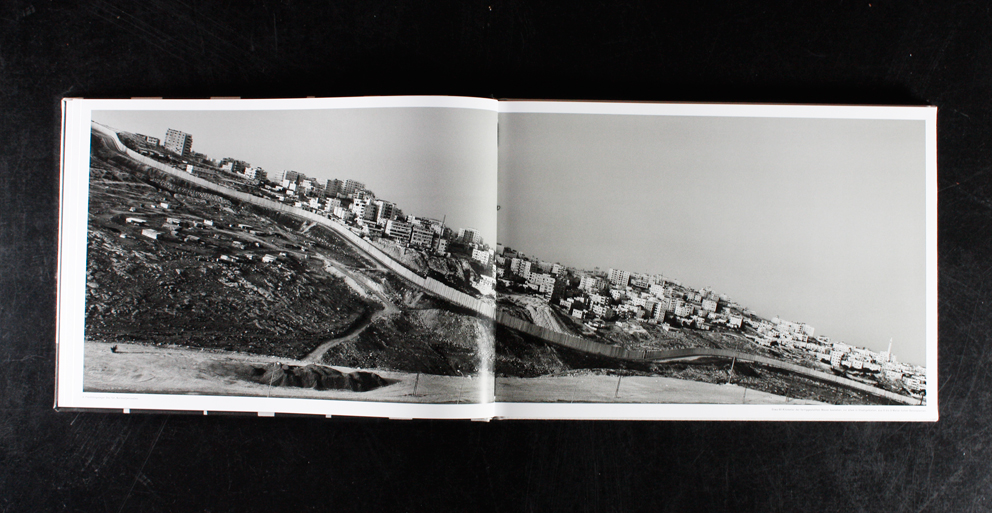

For his new photo book “Wall” Koudelka has focused his lens on Israel, more precisely on “Israeli and Palestinian landscapes 2008 - 2012”. By way of preparation the Magnum photographer took four extended trips before he decided to participate in a project with the working title “Israel: Portrait of a Work in Progress”, to which French photographer Frédéric Brenner invited 12 fellow photographers, among them Thomas Struth and Jeff Wall, Stephen Shore, Fazal Sheikh, and Nick Waplington. After some deliberation Koudelka consciously chose as his theme “the wall”, i.e., namely that built by Israel’s authorities as a border on the West Bank in April 2002 following a series of terrorist attacks.

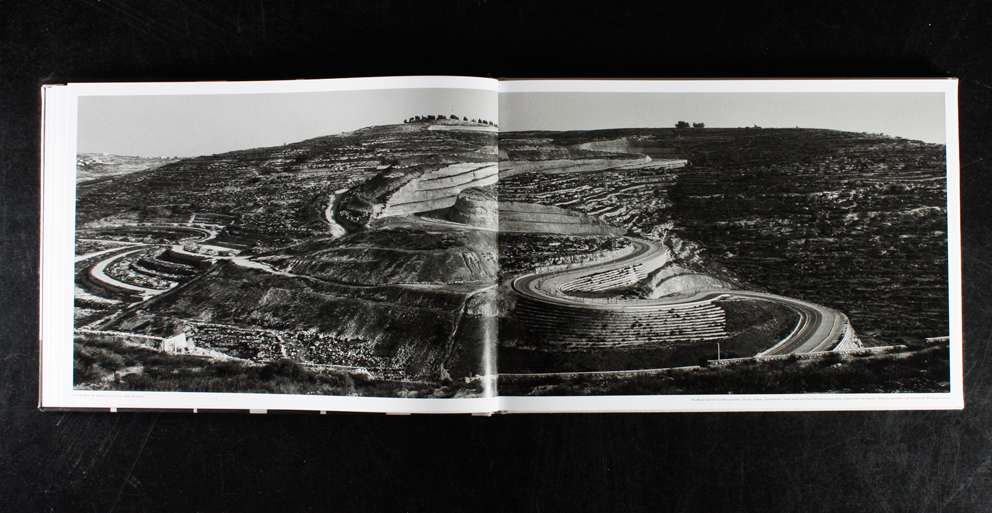

The photographer approached this theme from a vast variety of different angles, albeit always in a panorama format. There is a birds-eye view that shows a circle of concave prefab parts destined to protect a tunnel entrance from attacks. Intriguingly, the concrete wall here somehow has the qualities of “land art” – as if a Tony Cragg sculpture had crashed into the barren landscape. In Hebron, Koudelka gives a front-on view of a bricked-up intersection, including closed shop doors and drawn shutters in adjacent buildings. This is an all-round documentary, in the very sense of the word, but the impression it leaves is at best ambivalent: It’s difficult to decide if what we see is deadly silence or the typical calm of many an Arabic city on a holy day.

The subtle vagueness in Koudelka’s photographs, which appear very powerful at first glance, may ultimately work to inspire contemplation in the spectator – if it were not for the captions: Ostensibly informative words keep steering our perception in the same direction. “The majority of stores in Palestine”, we read below the Hebron image, “had to be closed as a result of bans imposed by the Israeli Defense Force and threats and harassment at the hands of the Jewish settlers.” There is not a single word about the traders’ and storeowners’ strikes during the intifada, nor is there a photograph to show this. Yet at the beginning of the project Koudelka had declared he intended to reveal “how the two sides handle the separation very differently”.

Indeed, if that was Koudelka’s original intention, it is hardly discernible in such monumentally staged photography. Which points to a rather serious problem that cannot be attributed to Koudelka’s penchant for the panoramic camera alone: “The Wall” overtly represents the ultimate in state-of-the-art strongholds and cutting-edge technology – which can nevertheless be outsmarted, if simply by digging a tunnel or sending Palestine street kids on errands. And there is another aspect to this, for beyond this visible “borderline” a periphery of bars, barriers and ambushes most certainly exists. This virtual and therefore all the more effective “wall” is reinstituted daily – with thermographic cameras and infrared sensors, mobile phone monitoring and surveillance by drones.

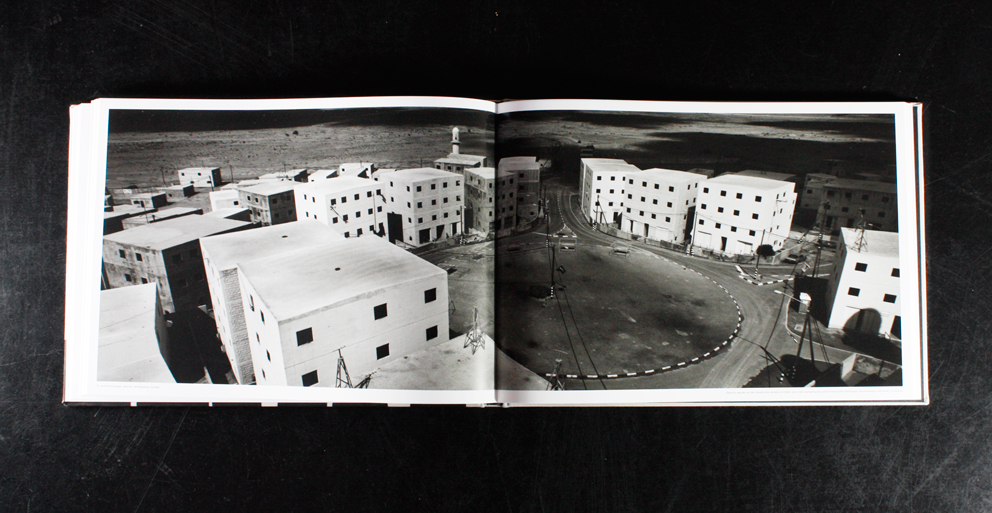

Putting all of this into words is certainly not easy. And yet, despite their pithiness Koudelka’s captions at least succeed in pointing to new possibilities in photography. An example: The silhouette of the Al-Eizariya district in East Jerusalem, which alludes to a gigantic heap of rubble, has rolls of barbed wire draped in front of it by way of symbolism; below the image we read the lament: “The wall is the largest infrastructure project in Israel, but to date no studies have been carried out as to how it may impair the environment.” It is precisely this aspect that Eyal Weizman already explored some time ago in his comprehensive analysis of “prohibited areas” in Israel, using photos and aerial shots, maps and computer renderings. Moreover, architectural theorist Weizman draws attention to a new tactic used by the Israeli Defense Force, which is indeed revolutionary. Inspired by Gilles Deleuze’s “philosophy of the rhizome” the soldiers make their way to the other side, invisibly and underground, off the streets and instead through basements and through the walls of residential homes, in an effort to evade snipers and ultimately take the enemy (who is difficult to pinpoint) by surprise. To master these skills of overcoming walls, the Israeli soldiers practiced in a mock city named “Detroit”, a reconstruction of a Palestinian settlement. Of course Koudelka came here to take photographs. However, his images show us residential homes that are completely intact, newly plastered concrete cubes gleaming with bright louvered façades. If you want to find out what goes on behind (and more to the point: below) these sleek structures you will need to turn to Adam Broomberg’s and Oliver Chanarin’s photo essay “Chicago”. The photographic duo went to explore the Israeli Defense Force’s eponymous combat training area with their camera and unearthed plenty of what they call “frontier architecture”. Ultimately, however, it is not the images of barriers and borders, but indeed those of remote traces and seemingly insignificant relics of mock urban warfare that will make us realize that “Everything going down now was first practiced here.”

To conclude, let us say that as such we have no objections against Koudelka’s panoramic camera – but we would urge the photographer to broaden his horizon accordingly.

Josef Koudelka: Wall

Israeli and Palestinian Landscapes, 2008-2012

Aperture Books, 2013

Clothbound hardcover, 128 pages, black-and-white images,

US-Dollar 60,00

www.aperture.org