Aimed at the 71% of British consumers, who according to a poll, know little or nothing at all about 3D printing, this exhibition is a very welcomed one: “The Future is here” tackles concerns about new digital technologies and simultaneously aims to alter the public’s perceptions as to the possibilities ahead. The result is an interactive and involved exhibition curated to empower consumers and designers alike with a display of all-encompassing examples of the most innovative processes, products and industries. Deyan Sudjic, the director of the Design Museum, conceived the idea for the exhibition during a “Meeting of the Minds” debate held at the British Museum in 2011, where it became evident that the promising young design talent working in the UK and the manufacturers of the new digital technologies were not working together as well as they could. In the long term such teamwork could engender new business opportunities and stimulate economic growth. Not surprisingly, the exhibition is supported by the Technology Strategy Board (TSB), a public body reporting to the government, set up to accelerate innovative technological solutions within UK businesses.

Kit Malthouse, the Deputy Mayor of London for Business and Enterprise, in his opening talk equated the role that new digital technologies play in UK manufacturing to Britain’s historical world leadership of design and innovation during the Victorian industrial revolution. Hence, the curator boldly declares a “New Industrial Revolution” where innovative digital technologies provide alternatives to traditional manufacturing processes and potentially have similar implications for the way we live as significant as the invention of steam engines and railways had on the population of the nineteenth century.

Accordingly, at the entrance, there is a Bruce Nauman-inspired neon sign which alternates “The Future is here” and “The Future was here”, and which illuminates illustrations of key inventions to narrate the events and repercussions of the Victorian industrial revolution. This brief history lesson ending in 1989 at the “Dawn of the Internet Age” is framed by laser-cut acrylic, creating a background that morphs from rural countryside to a cityscape defined by chimneys and factories.

Leitmotifs that emerged with the industrial age such as automation, standardization, economies of scale of traditional manufacturing processes and the social, political and environmental ramifications are key topics that form the core structure of the exhibition narrative.

Experimenting with 3D printing

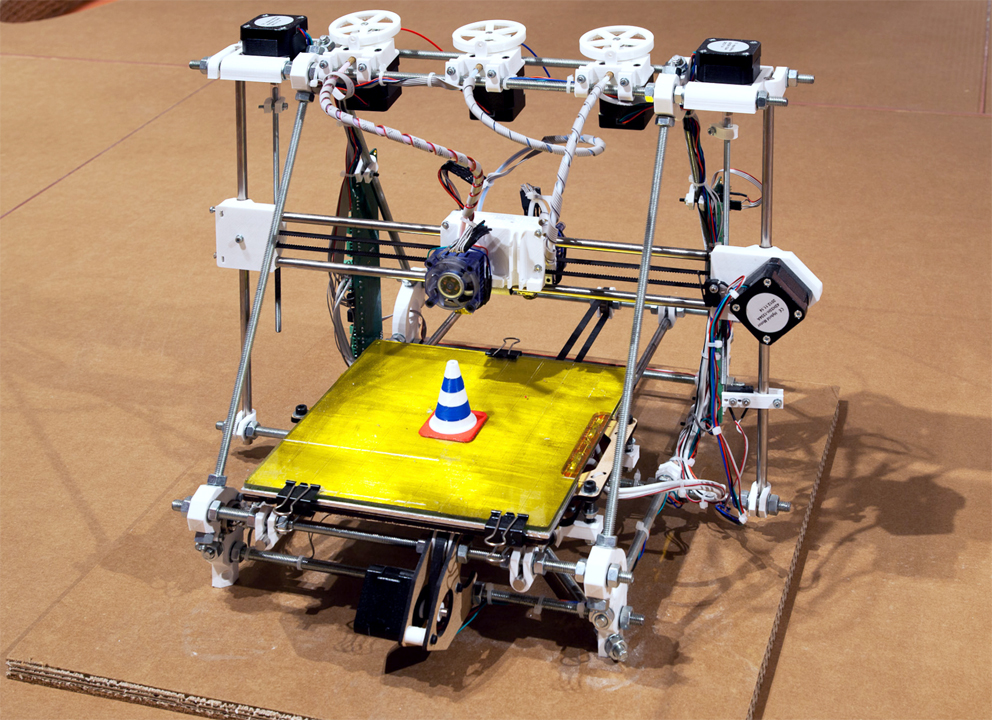

The exhibition’s digital factory is equipped with a variety of desktop-sized machines suitable for different tasks that the visitors are invited to explore.

3D printers can be programmed to produce any three-dimensional object in various materials from a digital design. This process avoids specialist machinery tools and huge expense and thus forms the basis of the revolutionary nature of this technology and a key proposition of this show.

Ron Arad’s design creative processes have been shaped by the digital era. His studio was one of the earliest to use computerized manufacturing processes to create a retail object. In 2000 Ron Arad created a series of “Bouncing Vases” designed by a chance computer-generated animation and produced by laser sintering (SLS), another 3D system. This process ensured that each object was unique and satisfied the discerning design collector. A decade later, the studio explored functional characteristics that can only be manufactured with 3D printing technology.

For Pq Eyeware, Ron Arad created sunglass frames that are built from nylon powder with hinges that behave like animal vertebrae along a spine. Doing away with the traditional hinge made of metal pins and pivots, the side arms allow an inward but not an outward bend and provide the best fit for the head.

Indeed, the Design Museum exhibition features a range of products that are only achievable by using 3D design technologies. Key to 3D printing technology is the possibility of individual customization. This is illustrated by Catherine Wales “Project DNA Feathered Shoulder” which is part of a fashion collection of bespoke sculptural pieces that can be printed to fit any body shape.

Although technologies of the digital era such as 3D printing have advanced exponentially in the last decade many of the digital or numerically controlled processes have gradually evolved from advances made in previous centuries. Invented in 1801, the Jacquard loom was controlled by cords linked through cards with punched out holes that could be read by a machine and hence this was the first machine that could follow a set of instructions. The essential process remains the same even though digital knitting and weaving machines are no longer controlled mechanically but electronically from computer files.

Industry led innovation

Whilst the Jacquard loom helped to revolutionize the textile industry in the nineteenth century, today’s applications of looms using digital technologies are not specific to one industry but are far more wide-ranging. For instance, the exhibited TC-2 digital loom developed by Tronud Engineering can be used for rapid prototyping and in this way works like a three dimensional sketchpad to help visualize ideas and concepts. Equally, it has the capacity to produce customized designs of high end textiles. In order to build the new “LFA super car”, Lexus invented a special loom to weave carbon fibre, essentially employing 3D weaving technology to build more efficient cars by reducing the volume of materials but increasing their strength.

The displays provide ample evidence of how high value manufacturing industries, especially automotive and aerospace sectors, have been crucial in their commitment to invest in developing new technologies. Rolls Royce, for instance, has spent more than 7.5 billion British Bounds in nurturing innovative ideas from concept through to production stage, resulting in developments such as the Trent 1000 titanium turbine blades exhibited here which were designed and manufactured for Boeing’s Dreamliner project.

Managing consumption

Customization being one of the key benefits of computerized 3D printing is the thread that runs throughout the exhibition narrative. The production processes of the small scale car company, Tesla Motors, are able to make individual car models using several robotic arms that simultaneously follow different computerized instructions. In this instance using digital production techniques allowing the manufacturer to cater for individual needs and replace the traditional standardized form of automated mass production established by Henry Ford exactly one hundred years ago.

On a different level, a small east London furniture company similarly employs digital tools to avoid dependence on standardized industrial processes. Unto This Last is named after the mantra of Victorian critic John Ruskin who advocated a return to local craftsmen workshops. Here all objects are made to order and produced within a day made possible with Computer Numerically Controlled (CNC) routing from plywood sheets. Aimed to shorten production time and simplify the supply chain, however, the aesthetic of the objects is determined by the limitations of its production method.

The exhibition displays reveal plenty of examples of how the possibilities of digital production have enabled brands to offer the consumer personalized goods. The “mi-adidas” range invites the customer to create their unique trainer. Makies provides an alternative to mass-produced toys, allowing the customer to design their own digital action doll model that is then 3D printed and dispatched.

A less gimmicky and more futuristic application of digital fabrication is the “Femurstool” designed by Assa Ashuach and printed by a 2T RPD machine. The shape of the chair is not designed to the dictates of taste or fashion but generated by an algorithm based on the weight and proportions of the person for whom the chair is made. Any change in weight will change the shape of the stool and thus is a promising example of truly customized design, made possible through digital technologies without the need for expensive tooling or mass production facilities.

Saving the planet

What makes digital technologies especially viable is their capacity to offer solutions for sustainable production and to help increase the lifespan of products. One section of the exhibition is introducing products of mass-market manufacturers that incorporate their own “unmaking” right at the beginning of the design process. The “Do Task” office chair made by Orangebox has been designed so that it can be quickly stripped into its component parts which can then be recycled into a new product. Puma’s “InCycle” trainers are made of non-toxic biodegradable materials that can be composted and break down to their original building blocks once worn out and thrown away.

Despite the usual short life of fast evolving technologies, the “Wandular” reverses this and lengthens the life. Developed by Sony, it is a concept for a multipurpose digital core device that is modular and attaches to other objects to ensure the host object can last a lifetime.

The “Optimist Toaster” has been designed to create an emotional attachment with its birthdate etched into the aluminum shell and a counter that tallies the slices of toast. The shell of the toaster is virtually unbreakable and the electrical units can be replaced via a simple clip mechanism. Should the toaster lose its charm, the toaster can be melted down and the material reused.

A dynamic new society

The last section of the exhibition attempts to explain the intangible impact of new technologies on the social environment. Social networking and online payment systems have already changed the music, film and publishing industries.

Emerging technologies have enabled an unprecedented involvement of the consumer in the manufacturing and design process. Computer terminals are provided in the exhibition so that the uninitiated visitor can discover open-source platforms like www.opendesk.cc that allow users to download construction plans for furniture or even plans for CNC-milled houses provided by an open community of designers on www.wikihouse.cc.

These technologies blur the boundaries between the designer and the consumer. However, the Mori poll showed that the majority of British consumers are still reluctant to actively engage with the possibilities these technologies offer. To demystify the process of crowdsourcing, the online furniture manufacturer Made.com together with the Technology Strategy Board invited the public to submit designs for a new compact two-seater sofa. From a shortlist of 60 3D printed sofa models, the “Love Bird”sofa displayed in the exhibition was selected by the public via the vote section on Made.com.

Local UK government initiatives such as “Assemble and Join” pioneer micro-community manufacturing by inviting local residents to change shared public spaces to better suit their needs. In the next decades it will become manifest if these new technologies will have triggered social change on the scale of the previous industrial revolution. It is quite likely that Karl Marx, who believed that those who control the means of production control political power, would have welcomed such collective dynamics heralded by this “new industrial revolution”.

The Future is here: A new industrial revolution

Design Museum, London, til 29 October 2013

www.designmuseum.org

www.the-future-is-here.com

www.ronarad.co.uk

www.teslamotors.com

www.miadidas.com.au

www.assaashuach.com

www.made.com