Stand still and gaze over the Med

I. Erwin Wurm or a little fun is OK surely

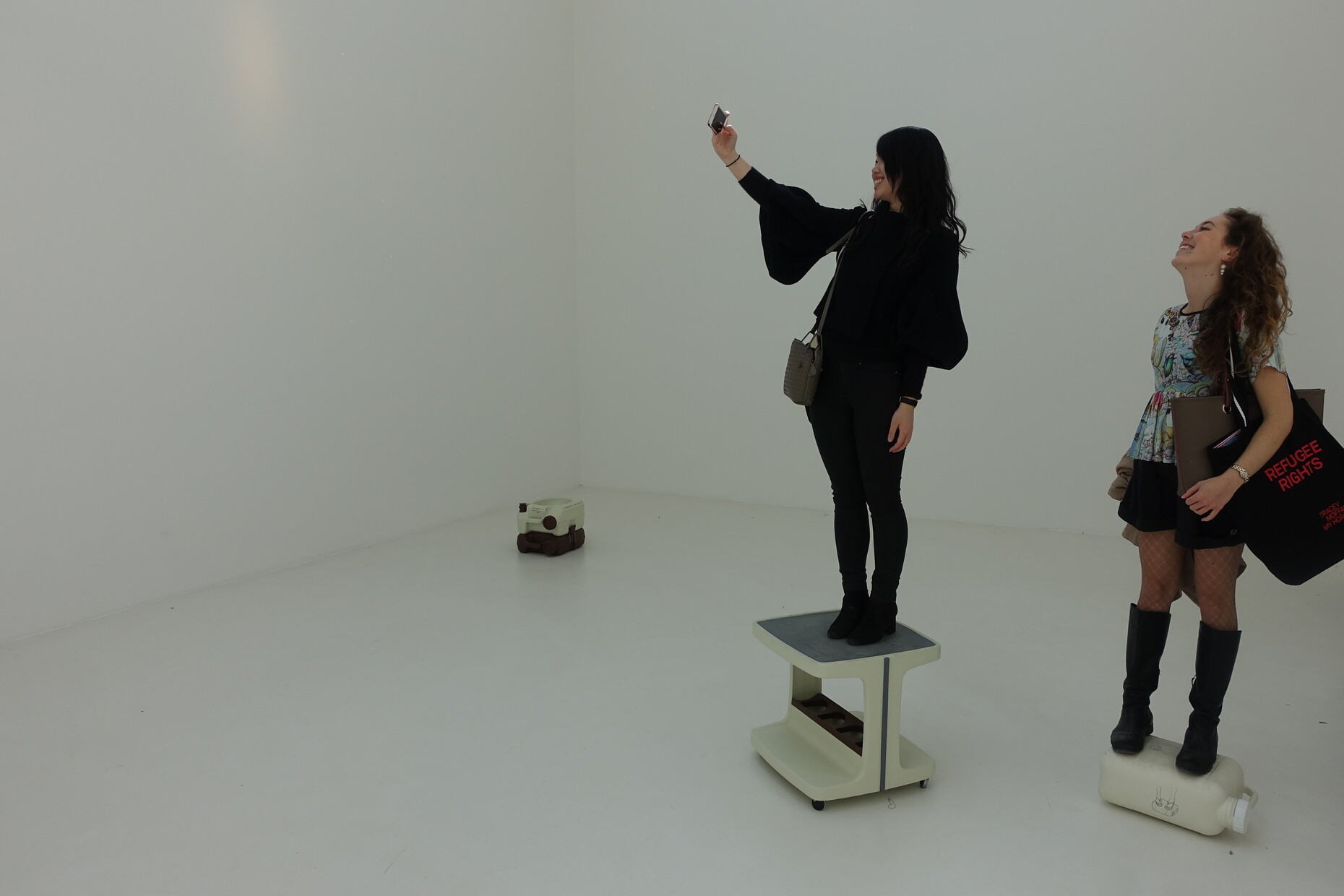

Erwin Wurm, who exhibits alongside Brigitte Kowanz in the Austrian Pavilion, is a master of manipulation. He offers visitors a little stick by way of instructions, and they swiftly take part and make a mockery of themselves, hang their bums out of a hole in a caravan or clamber onto a kitchen sink to present themselves to all others as a living sculpture. Sur, a little fun in in order. In the form he has devised for audience participation, Wurm’s successful “One Minute Sculptures” reveal also how much the need has grown to take part oneself, to stage oneself, and upload selfies or videos immediately into the relevant electronic networks. Participation as a sweet game of self-presentation with no effort, that’s how art for everyone functions today.

In front of the pavilion, Wurm has stood a small truck on one side and turned it into a viewing platform. Once you’ve clambered through the cargo section and reached the top, you encounter instructions: “Stand still and gaze over the Med.” To be exact, all you see is the lagoon, but the sentence applies as a motto for much of what will be on show as current art in Venice until November. As usual, the art biennial disintegrates into the national pavilions in the Giardini and around town designed by various curators and artists and the central exhibition at the Arsenale and the Padiglione Centrale – and this show, entitled “Viva Arte Viva” proves to be the larger problem. The current art in it proves not to be very vibrant.

II. Christine Macel and concepts

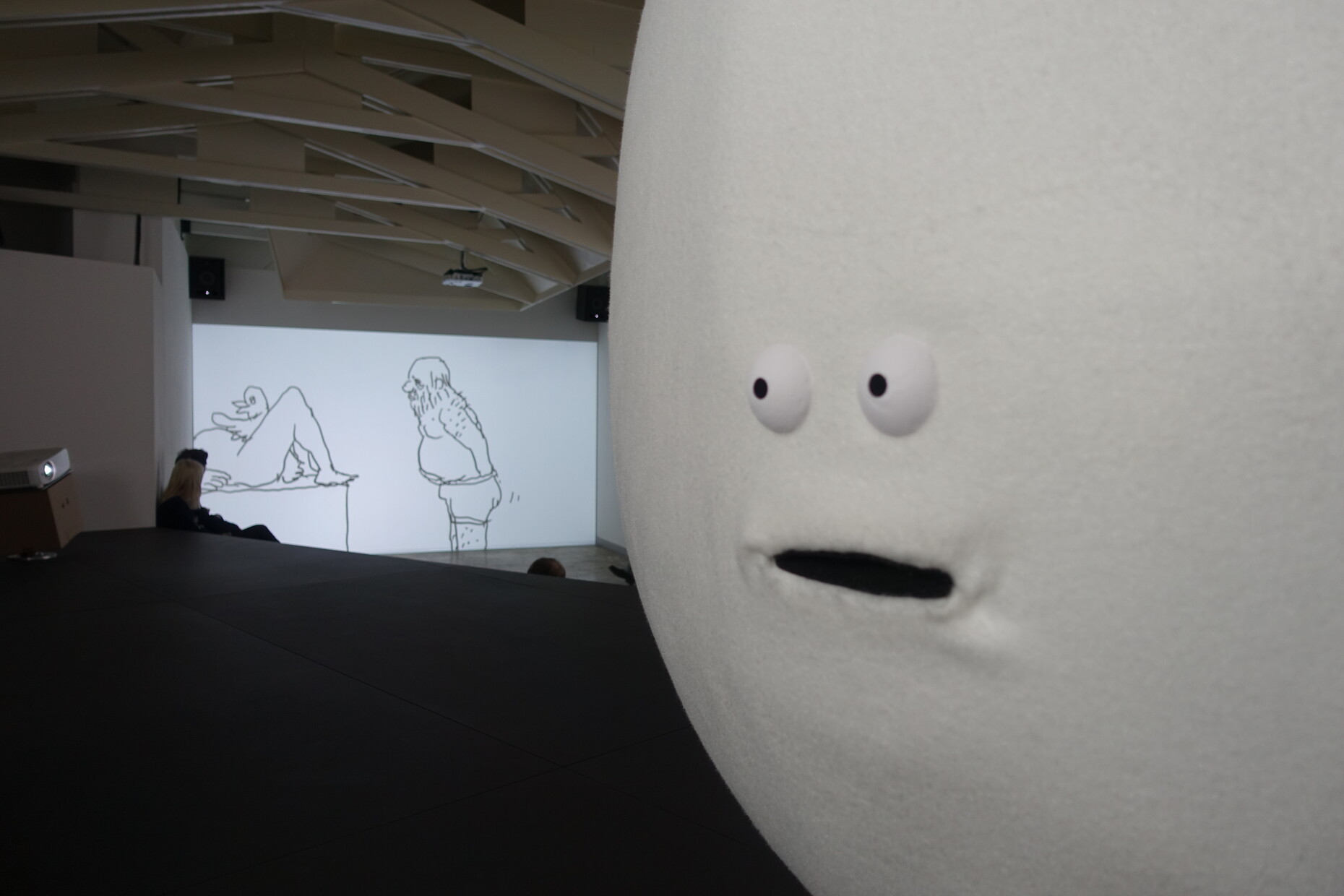

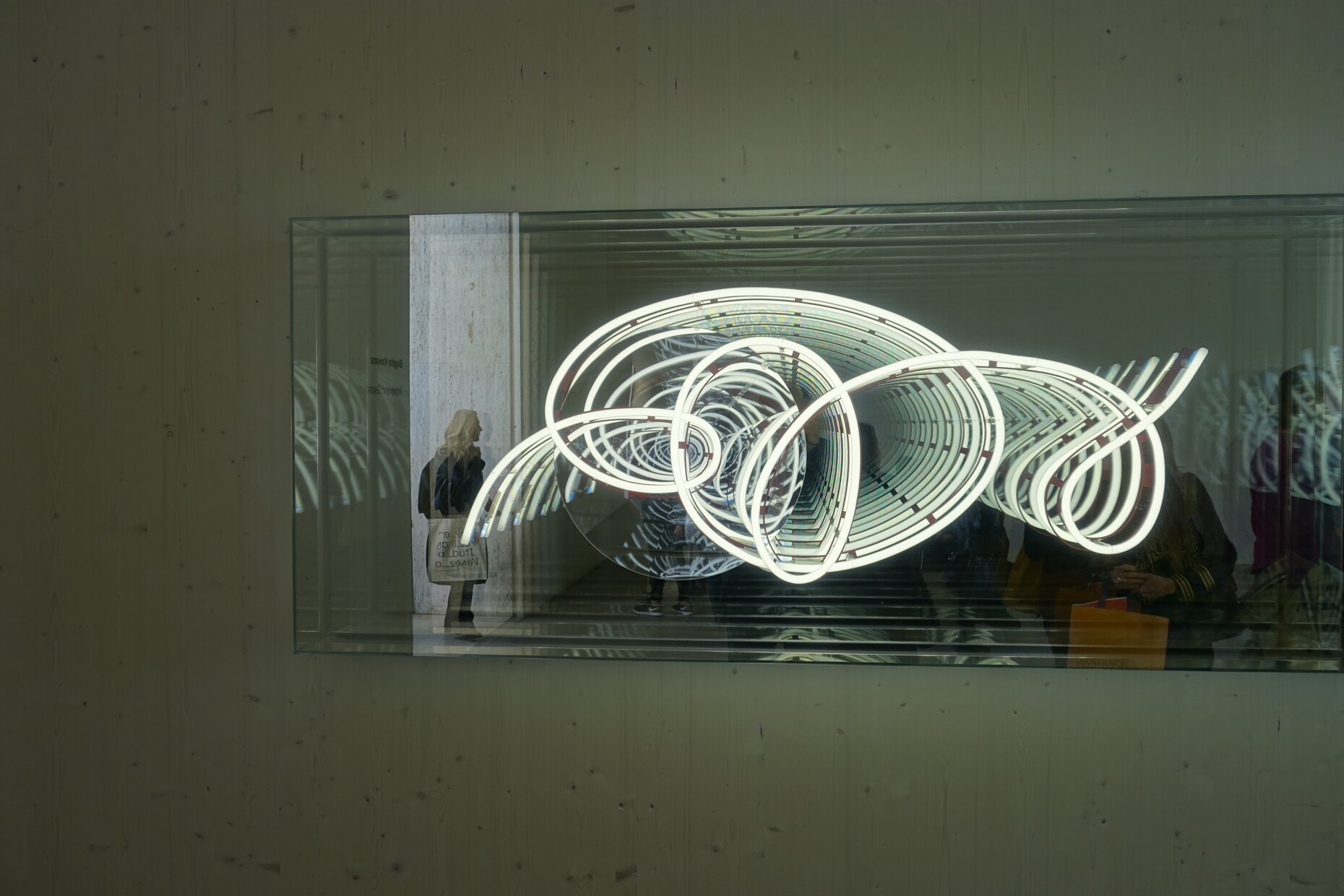

There are most definitely great works to be seen at this Biennale, including in the central show. And not seldom the pieces are more or less historical in stance. The fact that Franz Erhard Walter, born in 1939, was voted best artists at the “Viva Arte Viva” and won a Golden Lion speaks for itself and shows how opaque everything it, how manifest the uncertainty. Is it only nostalgia if (to cite another example) in one room at the Padiglione Centrale, dedicated solely to the works of ironical co-founder of the Nouveaux Réalistes Raymond Hains, you suddenly breathe a sigh of relief as what is on display here is formally consistent, complex, reflected, ironically refined and playful? Or does this response indicate more how arbitrary standards now are, how unstable and dubious the pigeonholing to date of the production and reception of art? Here you can’t simply participate, but you find out a lot about how we perceive the world and how things unfold in the world of art.

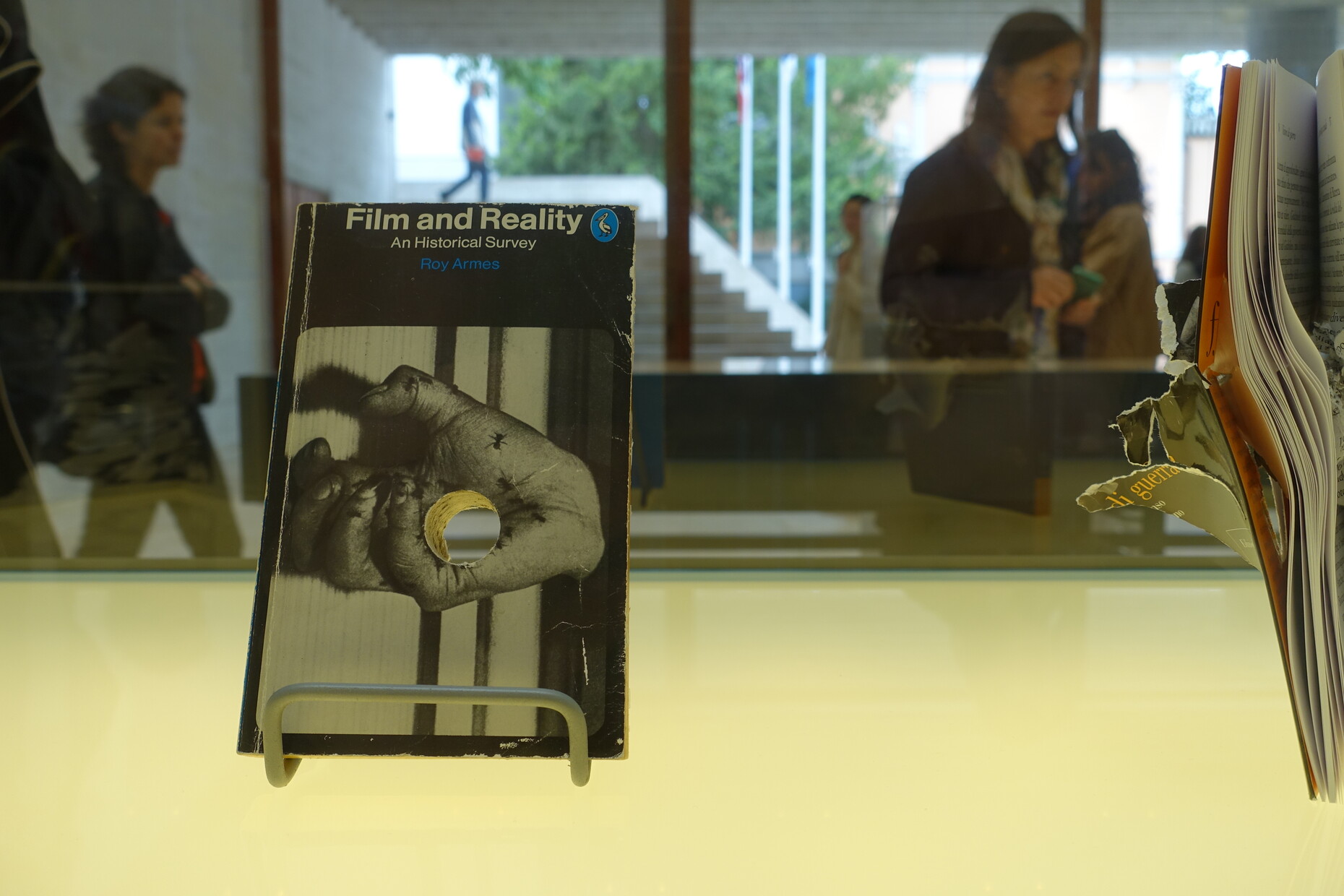

And what does Christine Macel do – she curated the central exhibition in which these works are likewise on show? Instead of creating tension between such pieces and completely different ones and exploring what has changed socially and in the media and in art in recent years, she orders art according to concepts in departments that she likewise calls pavilions and thus degrades them to the status of illustrations and proof of her, to put it kindly, dubious understanding of art. Things start in the “Pavilion of Artists and Books”, with Ólafur Elíasson inviting visitors to join refugees and asylum-seekers in assembling lamps he has designed; the proceeds go to charity apparently. The refugees do not get paid, but there are free language lessons. Maybe as workers for a global player among the grand artists they also learn what the hierarchies are in art and how something well-meaning swiftly becomes cynical exploitation.

Even when the focus is on “Joys and Fears”, Macel sacrifices art to her categorization. And completely so in the Arsenale halls, which evoke the “Pavilion of the Common”, the “Pavilion of the Earth”, the “Pavilion of Traditions”, the “Pavilion of Shamans”, the “Dionysian Pavilion”), the “Pavilion of Colors”, and that of “Time and Infinity”, the exhibition falls far short of the possible and continually gets lost in abstract fantasies on improving the world.

III. Faust or the Body and the Media

The question is not whether the relationship to things changes in general owing to networked digital communication, whether hitherto valid and largely stable social consensuses teeter and different forms of perceiving the real arise in art. The question is how art responds to this, how it tackles it, above all whether it not only evokes interventions and upheaval, not only cites the power of a new beginning, but actually produces such. Is it not a strange sign if the curator of a major museum complains that, while one event hounded the next outside in the big world, that the central Biennale exhibition seemed like an island inhabited by natives?

Paradoxically, in Venice many artists claim that what they display is political, is resistance and reflects current power relationships. On closer inspection, it is an abstract claim at most, rarely innate in a form that makes it valid, touching, sincere in the first place and distinguishes it from a journalistic allusion to an ostensibly important topics populated with pictures. Too much here is moralizing and relies on simple aesthetic effects. Good intentions are simply illustrated. To join hands and rely on myths and shamans does not revitalize some origin, nor does the woolen, embroidered and pottered per se serve as the elixir of a contemporary form of resistance.

Even the body, much injured or in part efficiently optimized, goes under in the media’s circulation processes, gets fragmented. It doesn’t really matter what you think of the martial staging of “Faust”, which brings to mind the terror of transparency and the lost nature of the bodies acting in it, for which Anne Imhof and the German Pavilion won a Golden Lion. Anyone who tried during the opening days to view performance, which take some five hours as a whole, saw a mass of people and thus very little, saw if anything at all above all the screens of the countless Smartphones people held up. A position from where the real viewer can perceive a piece in its entirety is evidently no longer part of the plan. Instead there are scraps, parts and fragments that can be spread without delay via the electronic networks. Even the instructions what the performers should do next are sent to them by the artist by sms. All of that guarantees success today – and not art as art.