Tent roof and cable-net structure: Tanzbrunnen for the Bundesgartenschau in Cologne, 1957, Frei Otto with Ebwald Bubner. Photo © Universität Stuttgart, ILEK

Fabric makes home

|

|

by

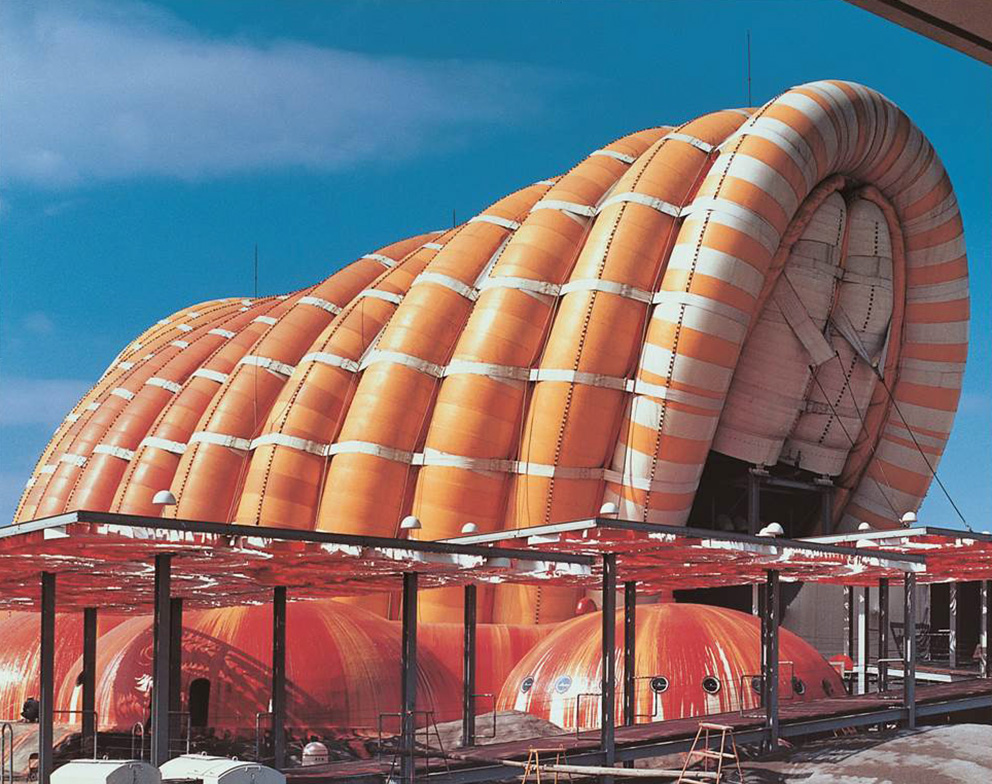

May 1, 2001 Canopies, umbrellas, tents, balloons – many are the origins of textile buildings and they can be traced back through the millennia. The tent, that primordial form of human accommodation, also affords nomads to this day with protection against inclement weather and inquisitive eyes. By contrast, sedentary peoples have from Classical Antiquity to the 19th century only used tents for military or courtly purposes, and later as temporary roofs for market fairs and festivals. The structure consisted of a frame covered by a tarp, such as is still used for circus tents today. In the 1950s there was a burst of innovations in such structures, with the tent also being discovered for architecture. “Is it not strange that (...) around the world the good architects are building tents, light, open affairs?”, asked post-War architect Hans Schwippert in 1951 during the “Darmstädter Gespräch” symposium on “Man and Spaces”. The trend was fueled in key ways by the work of architect-cum-engineer Frei Otto. His pre-tensioned membrane and cable-net structures presented a new form of building: light, mutable and geared to Nature’s design processes. Architects the world over were inspired by the studies and projects handled by his research establishments and the Institute for Light Load-Bearing Surface Structures in Stuttgart. Otto’s first tent structures, such as the Tanzbrunnendach, which he developed for the 1957 Cologne National Horticultural Show, were only meant to be temporary buildings and therefore covered with membranes made of cotton linen. Only a short time later, he opted instead for more durable plastic woven fabrics and foils, developed as of the mid-1950s for membrane load-bearing structures. Moreover, cable-net structures enabled larger spans to be covered. Frei Otto came to international fame with his design for the German Pavilion at the 1967 World Expo in Montreal. Together with Rolf Gutbrod he purpose-developed the first large pre-stressed cable-net structure in the world, which shortly thereafter functioned as his model for the roofing for the main sports venues in Munich’s Olympic Park, home to the 1972 Summer Games. While both buildings are not textile architecture in the narrow sense, they are among the pre-stressed load-bearing structures and have the same properties as membranes. In terms of uniqueness, they were thus decisive for ongoing developments in building with textiles. Too big for Olimpia The prize jury initially felt the sheer scale of the Olympics roof designed by architects Günther Behnisch and Fritz Auer was simply impossible. Yet the daring design won the day and was thereupon revised by several experts, among them Frei Otto. It was the latter who (using models made from stockings and lace) devised the saddle-shaped double-curved nets that enabled the huge roof with its 74,000 sq. m to be realized, and lent it the striking shape. While the cable-net structure in Montreal was fitted with a sub-roof membrane, in Munich’s Olympic Stadium the roofing consisted of transparent Perspex panels. At the time, to optimize the structure and the cuts of the construction elements the forces acting in the building components were simulated by complex measuring models. Nowadays such calculations are simply handled by fit-to-purpose software. The tent morphed from a mobile object into permanent architecture and today, thanks to improvements in the materials, is primarily used as a pre-stressed membrane structure for roofs for sports and trade-fair facilities and for industrial halls. Moreover, membranes are also employed as façade-cladding curtains or stressed membranes for vertical partitions, for example in Shigeru Ban’s “Curtain Wall House”. Thanks to their low weight, membrane load-bearing structures are especially suitable for creating mutable edifices. The Romans actually used “vela” (Latin for “sail”) to protect themselves against the rays of the sun, and in 16th-century Spain these then became “toldos” that can be gathered together. The folding roof designed by SL-Rasch for the inner courtyard of the Quba Mosque in Medina, built in 1987, obeys a similar principle – an electric drive extends or retracts the shade as needed. Moving roofs of this type tend now to be found covering sports arenas, such as that designed by Werner Sobek and Schweger+Partner for Hamburg’s tennis arena, the Rothenbaum: It can be opened and closed using radially aligned steel cables. Shade-screen structures are likewise used to shade inner courtyards, plazas and stages, and to provide ventilation and cooling. The first large mutable shades were created by Frei Otto together with Bodo Rasch and Edwald Bubner for the 1971 Federal Horticultural Show in Cologne. The largest mutable roof currently in existence consists of 250 large screens and was built in 2011 by SL-Rasch to provide shade over the piazza around the Mosque of the Prophet in Medina. While the shape of the above structures is defined by gravity, in the pneumatic versions the air actually creates the shape. Walter Bird undertook the first trials with membranes inflated by excess pressure back in the mid-20th century in the US. He was an aeronautic engineer and the US Army commissioned him to develop a non-metallic protective outer skin for the sensitive radar systems that were increasingly deployed after World War II. In 1948 he then succeeded in building the world’s first air-supported radome (protective skin for antennas) from neoprene-coated fiberglass fabric, and it was to become the role model for many an inflatable building. In Europe, it was once again Frei Otto who was the man to blaze the trail with this new building principle of using “air as the lightest construction material”; he started in an academic context studying possible ways of creating shapes. Like Buckminster Fuller, he also explored urban utopias and future habitats – and was inspired here by the reversal of traditional roles and structural principles as exemplified by the pneumatic buildings. Given the low material inputs required and relative ease of assembly, as of the 1960s pneumatic structures swiftly became a preferred construction method for sports hall or swimming pool roofs and for temporary pavilions such as those designed by Haus-Rucker-Co. The Austrian group of architects and artists made a name for themselves in the 1960s and 1970s above all with inflatable installations for public spaces. Today their ideas are models for many, for example, artist group raumlaborberlin, whose “Kitchen Monument” (a portable pneumatic pavilion) draws heavily on old designs. The pneumatic boom climaxed in 1970 with the Expo in Osaka – with countless pneumatic buildings such as the inflatable Fuji Pavilion by Yutaka Murata. Today, such pneumatic structures are usually only used for temporary pavilions for public spaces and increasingly as ETFE foil cushioning for façade or roofing elements. “I built little. But I dreamed up many ‘castles in the air’. Why the few real buildings that I myself made or collaborated on became so famous is a mystery to me, as the majority only existed for a short while,” Frei Otto once quipped. These “castles in the air”, his visionary ideas, his discoveries and research successes served to inspire innumerable architects and their impact can be felt to this day. In May of this year the architect will be honored posthumously for this – with the Pritzker Prize. Find about more about Techtextil www.techtextil.messefrankfurt.com “The construction material of the future”: “A new architectural skin“: “Fresh from the textile lab”: “A stitch in time”: |

German pavilion at the world exhibition in Montreal, 1967, Frei Otto with Rolf Gutbrod.

Photo © Universität Stuttgart, ILEK

Tested with stocking models: The conopy of the main sports arenas at the Olympiapark in Munich, 1972, Behnisch & Partner, Frei Otto, Leonhardt and Andrä with Jörg Schlaich.

Photo © Olympiapark München GmbH

Membrane roof, fixed with cables and cable masts, made of PTFE coated glass-fibre fabric: King Fahd Stadion in Riad, Saudi Arabia, 1985, Ian Fraser and Schlaich Bergermann und Partner. Photo © Schlaich Bergermann und Partner

Point-supported membrane construction, made of PTFE coated glass-fibre fabric, Department for waste in Munich, 1999, Ackermann und Partner.

Photo © Klaus Kinold, with kind permission of Ackermann und Partner

The main construction, made of steel supports and steel rings, covered by silicone-saturated shell of glass fibre fabric. Zénith concert hall in Strasbourg, 2007, Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas. Photo © Moreno Maggi_Zenith Strasbourg_FUKSAS

Quaba mosque in Medina, Saudi Arabia, with “Toldo”, which opens and closes.

Photo © SL Rasch

Flexible roof of the Rothenbaum stadium in Hamburg. It can be opened and closed via steel cables, which are radially arranged. Photo © Werner Sobek, Stuttgart

Inner courtyard of the mosque of the prophet in Medina with an open shield. In 1992, 12 convertible shields were installed in the two courtyards. Photo © SL Rasch GmbH

250 flexible shields are shading the Piazza surrounding the mosque of the prophet in Medina. Photo © SL Rasch

First air supported radome by Walter Bird for the laboratory for room air at the Cornell University of Buffolo, USA, in 1948. Photo © Birdair, Inc.

|

Kitchen monument, in 2006, by raumlabor – inspired by Haus Rucker, ant farm and Archigramm. Photo © Marco Canevacci, with friendly permission of raumlabor

|

“Oase Nr. 7“, at the Documenta 5 in Cassel in 1972, Haus-Rucker-Co.

Photo © Brigitte Hellgoth, with friendly permission of Ortner und Ortner |