Dieter Rams recently once again presented his "Ten Hypotheses on Good Design" – on the occasion of the "Business of Design Week" in Hong Kong, where German design was presented as the successful role model to emulate. Alongside Rams, highly popular product and communications designers highlighted their latest projects. In Hypothesis 2, Rams states that "good design optimizes utility and ignores everything that does not serve this objective or stands in its way." A sentence that was once read as a dogmatic limiting of design but could now be seen as encouragement for a despondent discipline. National design policy is a contradiction in itself: What could be more cross-cutting a field than design? Large German design studios have long since set up subsidiaries in Asia and South America. Yet design in and from Germany is by no means only an historical reference point (which Apple's Head of Design Jonathan Ive cites). It is still being thought up and designed here. But Asia is developing its own design strategies and training courses, often with German and European support. This is helping ensure that in future other value systems and preferences will define the map of design training.

Today, everything's supposed to be art

To date, a diverse range of training and education establishments was always a key reason for the quality of design from Germany. Now it faces a change in terms of content and structure that will fundamentally affect the way designers see themselves. It is astonishing that this change is taking place as good as unnoticed. Hitherto there has been no public discussion, let alone any controversial debate on the goals or strategies involved. However, above all in the art academies we are already witnessing a trend that could be termed the deprofessionalization of design.

"We are in the fortunate position," says Winfried Scheuer, who teaches Industrial Design at the Stuttgart State Academy of the Visual Arts, "that we can still rely on manufacturing industry." Whereby he and the graduate course in design that Stuttgart continues to offer, is as good as on his own. Another unique feature today is Stuttgart's well-equipped workshops. In an interview on teaching concepts, Scheuer wrote in 2006: "I train people but I don't really like the term 'training'. Essentially you create a playing field where students can to a certain extent test what they themselves want to make. Subsequent generations always come up with new ideas and I consider it wrong to place the solutions of your own generation in front of their noses."

Today, graduate design courses are a parallel universe. Anyone approaching them in order to describe or understand them will invariably fail. The public hardly takes any notice anyway. And certainly since the Bologona reforms there have been countless courses (often mainly attracting local students). Most of them hardly have any international glamour. Wherever you look, most of the former graduate courses have given way to Bachelor's and Master's courses with their specialization, profiles and segmentation. Often owing to a lack of suitable professors or the right curriculum they do not even aspire to be anything else. Or, to put it differently, there's a lack of intention and courage to change the world just that little bit.

In Hamburg, design has been made the handmaiden of art

Precisely that one cannot accuse Hamburg's University of Fine Arts (HfbK) of doing. And yet here design is no longer what it was only recently: Anyone wanting to study here, enrolls for a Bachelor's in "Fine Arts". The academy's Website states on "Focal Study on Design" that "the objective of this course is to introduce the students to the specialist context in which designers work, to support their personal artistic development and career decisions and train them to be responsible design personalities." So far, so good. For Master's students the goal is "in-depth Research, Development and Design practice with a design focus." However, "alongside the known, established design techniques" the focus here is on "artistic, experimental and innovative processes." The emphasis is on "artistic development", meaning design becomes part of art. Which also means no mass-produced items any longer, no object that could somehow spread the awful sense of the "applied".

Recently, three professors in design were newly appointed. They were artist and architect Marjetica Potrč (born 1953) from Ljubljana, as Professor for "Design for the Living World", architect, author, designer, artist and exhibition designer Jesko Fezer (born 1970) from Berlin as Professor for "Experimental Design" and Julia Lohmann (born 1977) from London. Lohmann is a designer whose best-known work was the limited edition of "Cowbenches" made of boiled hides and shaped like the cow beneath them, and she will teach an "Introduction to artistic work (design)". With this program and these appointments, the HfbK will finally bid farewell to any conventional design training. In future the thrust will more be on learning about design as an artistic strategy alongside others. Anyone intending at some future point to design mass-produced articles will possibly not be much helped here. Especially as the college's own workshops, or so one hears from lecturers there, will in future not be so relevant any more.

Knowledge, skills and creative abilities

It bears noting: it is less the actual example and program that bears criticizing and more a current that grasps design no longer as a profession interacting with others, but as a subset of art. For example, Gustav Hassenpflug, architect and Bauhaus member, saw things differently when in the mid-1950s he transformed the City of Hamburg's Art College into the HfbK – and his ideas were influenced by the Bauhaus. He had a vision of the HfbK as a cultural and economic dynamo that would link the "intuition of the free arts with technology". "Achieving this linkage is the real task of an art college today," he wrote in 1955.

Today, we in Germany still attribute the emergence of design as a profession to the "Bauhaus" and "Ulm" settings. However much this exaggeration may ignore rival and parallel developments, it is definitely true that both turned their backs on the conventions of the crafts and applied arts colleges. At the early days in Weimar the Bauhaus had each "Form Master" supported by a "Workshop Master". The more it focuses in Dessau on industrial production, the more crafts forms and techniques were cast into question. This certainly applied to HfG Ulm. It set itself off sharply from art and arts and crafts, but believed a knowledge of crafts was one of the bases for all design work. Ulm lecturer Tomàs Maldonado state, albeit somewhat hypertrophically from today's angle, that the task was "to raise people to think in a way that includes all factors, to have a knowledge of what they are doing and a clear sense of their task in society." And "a knowledge of what you are doing" presupposes skills. Indeed, "skills and knowledge," another Ulm professor, namely Hans Gugelot opined in 1964 "are two aspects of this activity that can be taught. Both together do not yet enable a person to be a designer." To that end, creativity was also required.

Since the days of Ulm, the world has fundamentally changed and with it design which now largely takes place at a computer. Precisely during training this creates the pretense of perfect results that do not then withstand much scrutiny when applied to work on a real product. How to switch between virtual and real worlds en route to final production without getting the wrong results is a problem, for example, of which the Ulm thinkers were largely unaware.

Entrepreneurs and later marketing buffs were later able to learn from the processual approach taken by design: proposal, test, rejection, revision, test, etc., i.e., planned trial and error that nevertheless ended with tangible results. Ulm taught conceptual thinking and activity – in workshops. This is the origin of what is today termed "design thinking". The lines demarcating design from art (and it was not a wall) that the Ulm lot drew were joyfully elided by later generations of designers.

Some designers succeed in winning over their clients by argument. They become stimulators and partners in the product development process. Others have succumbed completely to marketing strategies. They forgo developing their own theories and comprehensible reasons for their work. Instead of being partners, they simply become assistants. A completely different view of their role than that outlined recently by Walter Isaacson when describing the collaboration between Steve Jobs and Jonathan Ive.

Do designers also want only to be artists?

But who will develop, who will benefit in a conceptual/strategic sense if design primarily seeks to be artistic? Will the artifact thus made be better, indeed perhaps more useful? Is the public amused? Will it be enriched by new ideas or better products? For the generation of "New German Design" in the 1980s, breaking with the logic of industry was only partly a refusal. It was a matter of pride: If manufacturers lacked the courage to try out new paths then you simply had to go down them yourself. Things could be combined and collaged at will from semi-finished products, from materials left over by industry. Designers learned from artists, founded galleries and in garages and workshops busily banged together their own products, sold and distributed them. As the avant-garde before them, they sought to blend everyday life and design practice. This was a model that was only an enduring business success for a very few. When the Wall came down and many ex-Ulm lecturers retired, as of 1990 countless protagonists of "New German Design" became professors. Secured by tenured salaries, some of them ceased to be active designers. When did you last see an item ready for mass production developed by Volker Albus, Axel Kufus, Wolfgang Laubersheimer or Herbert Jakob Weinand? A design trend got cropped, chopped, and dropped. New academies arose, such as the Cologne model of the "Köln International School of Design", which merged communication and product design and presumed students had already completed vocational training, insisted on project work, and introduced new fields into design, from service to gender design. In Karlsruhe, the Academy of Design was founded and its first rector Heinrich Klotz promised that together with the Zentrum für Kunst und Medien (ZKM) the new Bauhaus would be born, a new 21st century Ulm.

In many cases, it is not teaching alone that has prevented designers from continuing to design. It is the academic bureaucracy, of which they are now a part. Administrative tasks, developing curricula and examination rules, paralyzing disputes with colleagues, the confrontation with the intrinsic laws of life at an academy all require time and energy. There's nothing new about frustrated professors and gormless students lacking willpower. However, they have a new and fatal impact in the age of "credits", where real feedback is not on the agenda. In the age of digital reinterpretation, when libraries and workshops purportedly hinder the creative process, they think their ambling approach is the new way forwards. And on occasion in doing so they set the standards for the academy.

The academy as black hole

Since the early 1990s, the academies have absorbed countless very promising designers who now only influence design output indirectly through their students. Many academies invest in publications, printed matter, catalogs, annual reports and comprehensive marketing activities. But they don't thus spark a general debate on the goals and values of design training. Anyone not going freelance will find there are few respectable jobs in business and industry. The idea of the designer as the generalist who knows the material risks dying out. Only few graduates in design are now able to cope with really complex tasks. Possibly you first experience how reality and dreams interlock in daily practice. If you think this through to the bitter end, the diversity of graduate courses spawns a kind of grey design economy in which one's own professional career was at best a short intermezzo between training and then becoming a professor.

Remark by the editorial department: The relation of art and design is intensely discussed at the HFBK Hamburg. An overview of several contributions to the discussion in diverse media can be found on the website of the school.

www.design.hfbk-hamburg.de

Further reading:

Designlehren – Wege deutscher Gestaltungsausbildung

By Kai Buchholz, Justus Theinert and Silke Ihden-Rothkirch

Hardcover, two vols., 424 pages, German

Arnoldsche, Stuttgart 2007

Euro 19.80

www.arnoldsche.com

Design Education

Ed. Hans Höger

Softcover, 176 pages, Italian / German

Editrice Abitare Segesta, Milan, 2006

Euro 22.00

For comprehensive documentation on teaching, teaching theory and practice

See Hans („Nick") Roericht

www.roericht.net

Car-engine or art-installation?, exhibit on the occasion of the design-prize 2011 at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg, photo © Imke Sommer

Car-engine or art-installation?, exhibit on the occasion of the design-prize 2011 at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg, photo © Imke Sommer

Racing-car “Exe“ by Samuel Burckhardt, photo © Imke Sommer

Racing-car “Exe“ by Samuel Burckhardt, photo © Imke Sommer

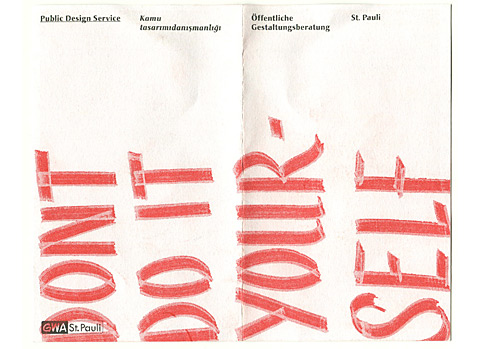

Students of Jesko Fezer at the HFBK Hamburg offer public design-consulting in St. Pauli, Flyer © HFBK Hamburg

Students of Jesko Fezer at the HFBK Hamburg offer public design-consulting in St. Pauli, Flyer © HFBK Hamburg

Flexible wooden chair by Daniel Kern at the HFBK, photo © Imke Sommer

Flexible wooden chair by Daniel Kern at the HFBK, photo © Imke Sommer

Metal workshop at the HFBK, photo© HFBK Hamburg

Metal workshop at the HFBK, photo© HFBK Hamburg

Modell making, photo © HFBK

Modell making, photo © HFBK

“Moody“ von Hanna Emelie Ernsting, photo © Philip Radowitz

“Moody“ von Hanna Emelie Ernsting, photo © Philip Radowitz

“Explosit” by Tina Becker, photo © Philip Radowitz

“Explosit” by Tina Becker, photo © Philip Radowitz

“Tape Pot“ by Peter Schäfer, photo © Philip Radowitz

“Tape Pot“ by Peter Schäfer, photo © Philip Radowitz

Achim Heine explains the design of one of his students, photo © Berlin University of Arts

Achim Heine explains the design of one of his students, photo © Berlin University of Arts

Chair-design at the department of industrial design at the Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design, photo © ABK Stuttgart

Chair-design at the department of industrial design at the Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design, photo © ABK Stuttgart

“Next Office“ at the ABK Stuttgart, photo © ABK Stuttgart

“Next Office“ at the ABK Stuttgart, photo © ABK Stuttgart

Uwe Fischer with a student at the ABK Stuttgart, photo © ABK Stuttgart

Uwe Fischer with a student at the ABK Stuttgart, photo © ABK Stuttgart

Form-studies from cardboard, photo © ABK Stuttgart

Form-studies from cardboard, photo © ABK Stuttgart

Students in the wood-workshop, photo © ABK Stuttgart

Students in the wood-workshop, photo © ABK Stuttgart

What makes a good sled? photo © ABK Stuttgart

What makes a good sled? photo © ABK Stuttgart

“Bow Bins“ by Cordula Kehrer were developed at the Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe, photo © kkaarrlls

“Bow Bins“ by Cordula Kehrer were developed at the Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe, photo © kkaarrlls

Exhibition by “kkaarrlls” during the Salone Internazionale del Mobile 2010 in Milano, photo © kkaarrlls

Exhibition by “kkaarrlls” during the Salone Internazionale del Mobile 2010 in Milano, photo © kkaarrlls

“kkaarrlls“ is the title of an edition-collection with circa fifty objects, their design dates back to the study-time of young designers at the HfG Karlsruhe, photo © kkaarrlls

“kkaarrlls“ is the title of an edition-collection with circa fifty objects, their design dates back to the study-time of young designers at the HfG Karlsruhe, photo © kkaarrlls

Visitors at the annual round tour at the Berlin University of Arts, photo © Berlin University of Arts

Visitors at the annual round tour at the Berlin University of Arts, photo © Berlin University of Arts

How e-mobiles will be refuelled in the future was the topic of a project by Winfried Scheuer and Ulrike Rogler. Here a design by Benjamin Erhardt, photo © ABK Stuttgart

How e-mobiles will be refuelled in the future was the topic of a project by Winfried Scheuer and Ulrike Rogler. Here a design by Benjamin Erhardt, photo © ABK Stuttgart