We're at the former Diskus-Werke factory on the outskirts of Frankfurt/Main, home to Jürgen Krause's studio. Where once grinding machines were made, Krause today grinds sculptors' tools. But not for functional reasons, as Krause is not a service provider and is instead interested in the activity itself. The constant grinding does not yield tools that can be used, and they're not there to be used, but as proof of the grinding process itself. Japanese masters, from whom Krause took lessons in the traditional craft of grinding, on occasion express a complete lack of understanding for the works the Frankfurt artist produces. It contradicts their notion of harmony if a tool is not used in line with its function. Krause does not let this unsettle him and continues to go about his work.

It is not easy to find his studio in the industrial complex. He tells me that he likes the seclusion but is also happy to receive visitors occasionally. He feels exchanging ideas with colleagues and friends is important. However, I'm not allowed to use my camera. He requests that I record what I see in words, instead. He recalls that he once considered scattering his works like confetti, back then they consisted of small paper discs – and not to exhibit the perforated papers. Then there would no longer have been any visible evidence of his work, only stories about it. I realize that the word constitutes a part of his artistic activity, just as do hiking and grinding tools. He seeks to consciously carry out each activity, and not be one step further on in his head. Thanks to his work, actions become visible that, by dint of being carried out, at the same time get left behind. His objects therefore resemble a demand that the viewer concentrate, be attentive and appreciate things.

In his studio he has, as he puts it, set up a "circuit training course". He progress from one stage to the next in the course of each day. He grinds tools, sharpens pencils, draws lines, cuts circles into paper, grounds wooden panels. He dedicates himself to each object until there is nothing more to be done to it, until when grinding a blade he ends up at the handle, or the pencil consists only of a lead or a stump, until the pages are completely covered in a diamond pattern or completely perforated, until the wooden panels have so much grounding on them that they are hard to turn over. The objects thus created are reminiscent of those that they once were, but their proportions have changed owing to the constant work done to and with them. With the tools, the blade takes a visual backseat, the handle becomes more important, as does the shape, the grain of the wood, the printed logo of the maker. Moreover, Krause's pieces bear clear traces of having been worked on. Chippings from grinding, grooves from cutting, streaks from painting, cut edges and brush traces are all means of artistic expression here. Sometimes, the short blade of the ground tools almost resembles a gem, given the careful polishing it has received.

Our conversation continuously returns to beginnings. "Nothing you do should be preparation," wrote author Ludwig Hohl. Krause quotes this as the motto for his catalog "Sculptors' Tools". He tells me a story about something that constantly happens at art academies. A professor sets his students a drawing task, and they all grab their pencils. For Krause this act constitutes the beginning of an artistic action that he places at the very center of his oeuvre. As if to encourage him in his everyday work, in his studio alongside his own pieces there are other items attesting to beginnings: blocks of material (graphite, chalk and alabaster) and a small collection of prehistoric tools, a blade, a sickle, and a polisher for beads.

Of course it seems doubtful whether actions that take years can still be classified as beginnings, as many of Krause's items reveal precisely the finitude of objects. As if in slo-mo, he seems to pre-empt their wear-and-tear, such that the "used" objects become a kind of memento mori. It would seem obvious to speak of Krause's works as repetitions. Sisyphus, who always pushed that rock up the mountain, Casanova, who hastened from one act of coitus to the next, a mantra that gets repeated a million times, all of these could be taken as analogies of Krause's daily work of grinding, sharpening, drawing, perforating, and grounding. Last year Jean-Christophe Ammann, the former director of Frankfurt's Museum für Moderne Kunst (Museum for Modern Art), held an address in praise of Jürgen Krause on the occasion of the artist being awarded the Rolf Seisser Prize. Ammann spoke of repletion, emptying, and enriching, including in the universal divine sense. By contrast, Krause himself emphasizes in the few sentences he has composed on his own work the potential innate in a beginning that can stretch across your entire life. He quotes by way of example the Japanese ideal of a master who considers himself a lifelong pupil: "That is the Japanese path to mastership, to unconditionally submit to a topic and to understand that despite all the effort, a residue remains that cannot be completely controlled. In outlook, you always remain a beginner."

Since 2002, Jürgen Krause has been sharpening the blades using a whetstone – and goes on sharpening them and sharpening them; here a carving knife, photo: Sascha Nau

Since 2002, Jürgen Krause has been sharpening the blades using a whetstone – and goes on sharpening them and sharpening them; here a carving knife, photo: Sascha Nau

Whetstone Ohmura, photo: Sascha Nau

Whetstone Ohmura, photo: Sascha Nau

Whetstone Amakusa, photo: Sascha Nau

Whetstone Amakusa, photo: Sascha Nau

Whetstone Suntiger, photo: Sascha Nau

Whetstone Suntiger, photo: Sascha Nau

For his works, Krause then has snug-fitting packaging made, photo: Sascha Nau

For his works, Krause then has snug-fitting packaging made, photo: Sascha Nau

To the wood or paper as the medium for the art, since 2002 Krause has then been adding many layers of grounding on both sides, photo: Sascha Nau

To the wood or paper as the medium for the art, since 2002 Krause has then been adding many layers of grounding on both sides, photo: Sascha Nau

Dried polishing-material attesting to Krause’s work, photo: Sascha Nau

Dried polishing-material attesting to Krause’s work, photo: Sascha Nau

Grounding, photo: Sascha Nau

Grounding, photo: Sascha Nau

Since 2000, Jürgen Krause has been using a knife to chip away the wood around the pencil lead in flakes – right to the bottom of the pencils, photo: Sascha Nau

Since 2000, Jürgen Krause has been using a knife to chip away the wood around the pencil lead in flakes – right to the bottom of the pencils, photo: Sascha Nau

Ripping chisel 10 mm, photo: Sascha Nau

Ripping chisel 10 mm, photo: Sascha Nau

Ripping chisel 20 mm, photo: Sascha Nau

Ripping chisel 20 mm, photo: Sascha Nau

Pocketknife, photo: Sascha Nau

Pocketknife, photo: Sascha Nau

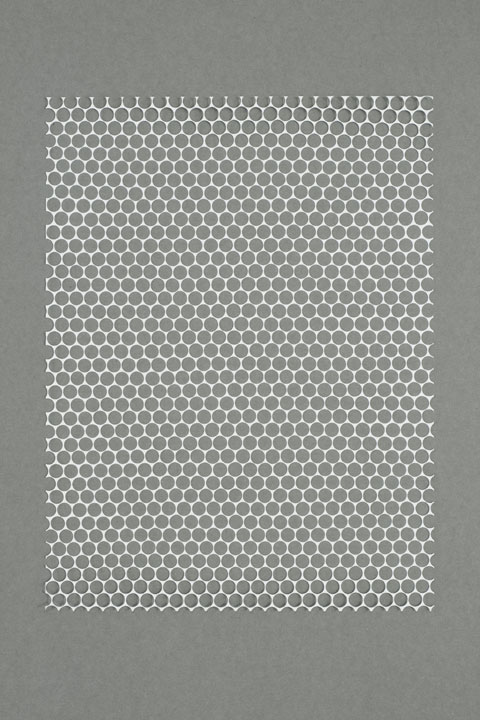

Jürgen Krause uses a knife and cuts by hand to create holes that are as round as possible in white sheets of paper. Since 1999 he has been using the paper discs thus obtained as confetti, photo: Sascha Nau

Jürgen Krause uses a knife and cuts by hand to create holes that are as round as possible in white sheets of paper. Since 1999 he has been using the paper discs thus obtained as confetti, photo: Sascha Nau

Sculpting tools and whetstones in an exhibition, photo: Sascha Nau

Sculpting tools and whetstones in an exhibition, photo: Sascha Nau

Exhibition view Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2005, photo: Sascha Nau

Exhibition view Kunstverein Nürnberg, 2005, photo: Sascha Nau

Cut paper page, 2006, photo: Sascha Nau

Cut paper page, 2006, photo: Sascha Nau